Organised by Elon Musk’s SpaceX and attended by members of Nasa’s Mars exploration programme, the goal of this inaugural “Mars workshop” was to begin formulating concrete plans for landing, building and sustaining a human colony on Mars within the next 40 to 100 years.

This workshop signals the growing momentum and reality behind plans to actually send humans to Mars. But while SpaceX and partners ask whether we could live there, others still ask whether we should.

A Pew Research Centre survey carried out in June asked US adults to rank the relative importance of nine of Nasa’s current primary missions. Sending humans to Mars was ranked eighth (ahead only of returning to the Moon) with only 18% of those surveyed believing it should be a high priority.

We have known for some time that the journey to Mars for humans would be hard. It’s expensive. It's dangerous. It's boring. However, like so many advocates of Mars exploration, I've always thought the sacrifice was worth it.

But – to test this belief – I wanted to look at the case against Mars; three reasons humans should leave the red planet alone.

Humans will contaminate Mars

It is hard to forget the images six months ago of Elon Musk's midnight cherry Tesla floating through space. Launched atop the Falcon Heavy, SpaceX hoped to shoot the Tesla into orbit with Mars. A stunt, for sure – but also a marvellous demonstration of technical competence. But not everyone was happy. Unlike every previous craft sent to Mars, this car – and the mannequin called Starman sitting behind the wheel – had not been sterilised. And for this reason, some scientists described it as the “largest load of earthly bacteria to ever enter space”.

As it happens, the Tesla overshot its orbit. At the time of writing, it is 88 million miles from Mars, drifting through the darkness of space with Bowie on an infinite loop. But the episode illustrates the first argument against human travel to Mars: contamination.If humans do eventually land on Mars, they would not arrive alone. They would carry with them their earthly microbes. Trillions of them.

There is a real risk that some of these microbes could find their way onto the surface of Mars and, in doing so, confuse – perhaps irreversibly so – the search for Martian life. This is because we wouldn't be able to distinguish indigenous life from the microbes we'd brought with us. Our presence on Mars could jeopardise one of our main reasons for being there – the search for life.

Furthermore, there is no one way of knowing how our microbes may react with the vulnerable Martian ecosystem. In Cosmos, the late Carl Sagan wrote, “If there is life on Mars, I believe we should do nothing with Mars. Mars then belongs to the Martians, even if the Martians are only microbes … the preservation of that life must, I think, supersede any other possible use of Mars.”

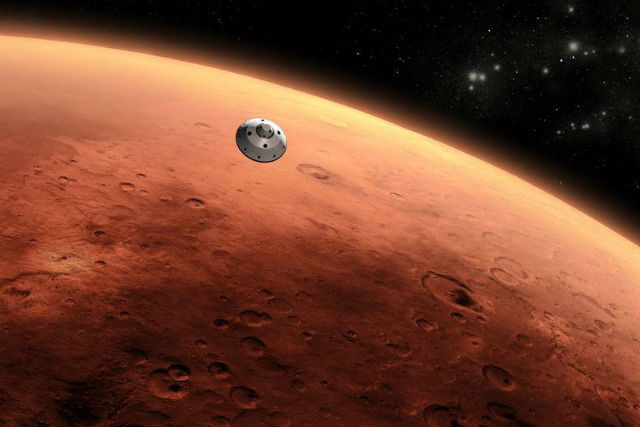

Photo: European Space Agency/Flickr. Image of craters on Mars generated using data from the high-resolution stereo camera on ESA’s Mars Express

Robots are better than humans

Of course, one easy way to minimise the risk of contamination is to send robots to Mars instead of humans – the second argument against a manned trip to Mars. Robots have several inherent advantages. They are much cheaper than humans because they don't require a vast support infrastructure to provide things like water, food and breathable air. They are immune to the risks of cosmic radiation and other dangers inherent to space travel. And they won't get bored. Over the last 40 years, the international space community has an extraordinary legacy of robotic missions to Mars.

A few weeks ago, the European Space agency's Mars Express identified liquid water buried in the south polar region of Mars.

The Curiosity Rover recently celebrated its sixth birthday with the discovery of organic molecules and methane variations in the atmosphere– both positive signals of life.

And while most of its targets are chosen by humans, Curiosity also uses artificial intelligence to autonomously analyse images and choose targets for its laser detection system.

With the rapid pace of progress in robotics and AI, it is likely that the effectiveness of these non-human explorers will only increase. Robots on Mars will be to able to carry out increasingly complex scientific research, accessing craters and canyons that humans might find too difficult to reach – and perhaps even drilling for Martian microbes.

Let's fix the Earth first

The most polarising issue in the Mars debate is arguably the tension between those dreaming of a second home and those prioritising the one we have now.

Before his death, Stephen Hawking made the bleak prediction that humanity only had 100 years left on Earth.

Faced with a growing list of threats – climate change, overpopulation, nuclear war – Hawking believed that we had reached "the point of no return" and had no choice as a species but to become multi-planetary – starting with the colonisation of Mars.

Elon Musk has also said on numerous occasions that we need a “backup planet” should something apocalyptic – like an asteroid collision – destroy Earth.

However, not everyone agrees. In the Pew survey mentioned earlier, a majority of US adults believed that Nasa’s number one priority should be fixing problems on Earth. The billions – if not trillions – of dollars needed to colonise Mars could, for example, be better spent investing in renewable forms of energy to address climate change or strengthening our planetary defences against asteroid collisions.

And of course, if we have not figured out how to deal with problems of our own making here on Earth, there is no guarantee that the same fate would not befall Mars colonists.

Furthermore, if something truly horrible were to happen on Earth, it’s not clear Mars would actually be an effective salvation. Giant underground bunkers on Earth, for example, could protect more people, more easily than a colony on Mars.

And in the event of apocalyptic scenario, it is possible that the conditions on Earth – however horrific – may still be more hospitable than the Martian wasteland. Let's not forget that Mars has next to no atmosphere, only one third gravity and is exposed to surface radiation approximately 100 times greater than on Earth.

So, what's the verdict?

The arguments above show that we are perhaps not ready to go to Mars – at least, not today. We need to first update our policies on planetary protection and apply them fairly to both public and private sector entities. We need to understand humans' unique role in exploration, beyond robots. And we can't lose sight of challenges on Earth, nor use the promise of Mars as an opportunity to deflect responsibility from Earth. But for me, the issue comes down to timing. The technology will not be ready to send a human to Mars for at least another 10, perhaps even 15 years. This is a good thing. We should use this time carefully to make sure that, by the time we can go to Mars, we really should.

By Zahaan Bharmal