Seven years ago, the Kremlin-backed TV station Russia Today went all in on coverage of a leftist street protest in the west. Did Occupy Wall Street fit the Kremlin’s interests of showing a western nation in (relative) chaos? Yes. But at that time, few would have suggested that OWS was anything but a genuine protest movement.

By contrast, then, it was autocratic governments, like Russia and the monarchies of the Middle East, who suggested that foreign coverage of the Arab Spring and the White Ribbon protests of 2011-12 were part of a vast plot from abroad.

Thanks to recent events, specifically the 2016 US elections, protests in the west are now treated with wariness, and France is already investigating whether it too has been a victim of Russian disinformation.

Projects that track Kremlin influence abroad, such as the Alliance for Securing Democracy dashboard, listed “#giletsjaunes” as one of the trending terms used by accounts “linked to Russian influence operations”.

The thinktank doesn’t name the accounts it monitors, which makes checking the reports impossible. But in this case it would be hard not to notice Russian media laser-focused on the protests and Russian online trolls doing what they love: trolling.

What similar studies do not measure is the efficacy of Russian messaging. Can fake Facebook groups or flashy RT programming prompt mass protest movements or significantly change voting behaviour abroad?

Grassroots, citizen movement

It is possible that time will come, but there is scant evidence to prove that it has done so already. For the moment, on-the-ground reporting shows that participants in the Gilets Jaunes have organic, significant causes for protest that are tied neither closely to Russia or to what they read online.

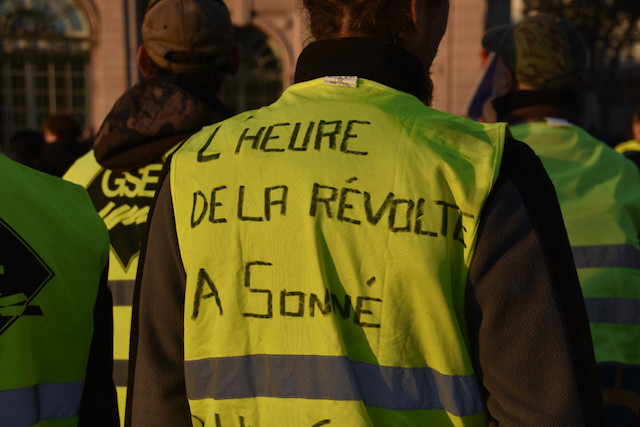

The gilets jaunes movement is a grassroots, citizens movement that has no leader or organised structure. The protests began in November against a proposed fuel tax that would have pushed up the price of petrol, affecting many people in rural and suburban areas who depend on cars, having little access to public transport.

On the barricades on roundabouts and at toll-booths in rural and suburban France, gilets jaunes demonstrators said they had joined the protests out of frustration with their struggle to make ends meet.

Although most had organised their protests via local Facebook groups or social media, many said they were protesting because of real difficulties in their lives rather than because of what they had been reading or watching online.

Trump's fake news

However, the French government has been attentive to foreign leaders trying to jump on the back of the gilets jaunes protests or use them for their own domestic audiences. And Russia has not been the only focus. Donald Trump falsely tweeted on December 8 that French protesters were chanting, “We want Trump!”

The French foreign minister, Jean Yves le Drian, said on French radio: “I tell Donald Trump – and the French president tells him too – we don’t take part in American debates. Let us live our life as a nation.”

Asked whether Russian tweets may have contributed to protests, he said: “I’ve heard those rumours. An investigation is under way by our secretary general of national defence. We’ll wait for the results.”

Russian television has given significant airtime to suggestions that Moscow is behind the protests, but used it to say the accusations just discredit the west. At the same time, it has also highlighted events that seem to suggest a connection between Russia and what is happening in France.

The Russia-24 state television station aired footage that supposedly showed protesters playing the Russian folk song “Kalinka” on a piano, which was later shown to be fake.

60 Minutes, a hawkish political talk show, interviewed a French protester who unveiled the flag of a Russian-backed separatist state in east Ukraine during the marches. The hosts urged him to take out the flag again. “This is just a joke,” he said. “But I would like the Kremlin to send me a million dollars.”

But none of that reflects the genuine interests of most French protesters, or indicates that Russian media has done more than jump on a bandwagon.