The earliest reference of a castle in Colpach-Bas dates to the 14th century. A local family, the Pforzheims, acquired what was then a medieval fortress and in the 1700s converted it into something more akin to a manor house. It was under power couple Baron Edouard de Marches and Cécile Papier that the castle would first become a hub for Luxembourg’s high society.

After her husband’s death, Papier married Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy and the pair used the house as their summer residence. Notable guests included composer Franz Liszt who stayed at the château in July 1886. During this visit to the grand duchy, he would give his last ever piano recital, at the Casino Bourgeois, now the Casino Luxembourg contemporary art centre.

Luxembourg steel magnate Emile Mayrisch acquired the property in 1917, two years after Papier’s death, and lived there with his wife, Aline. Both were passionate about art and literature but also philanthropy. Aline Mayrisch founded the Luxembourg Red Cross.

“When Aline Mayrisch died, she gave the castle and its ground to the Red Cross, to either create a rehabilitation centre or a facility for children,” said Jean-Philippe Schmit.

Schmit is the rehabilitation centre’s director general. The facility provides general care but also specialised rehabilitation for cancer patients during and after treatment. But none of the activities take place within the castle’s walls anymore. “We had foreseen it at the start,” said Schmit, but in consultation with the national monuments’ commission, the Red Cross settled on a new purpose-built facility next door.

Residents of a convalescent home, established to honour Aline Mayrisch’s 1947 will and testament, were moved to the new premises in 2010 and the building has since been standing empty.

Monthly inspection

Over the years, the Red Cross has been accused of letting it fall into disrepair, Schmit said. “If we hadn’t done anything, I think it would have collapsed by now,” he said about the château’s upkeep.

The building is inspected monthly for repairs, but any larger renovation works are pending a project to develop the site. Numerous ideas--a regional library, museum or tourism centre--have all come to nothing. And Schmit said he couldn’t imagine the historic site ever being turned into a commercial enterprise, such as a hotel.

“We are approaching a solution,” he said. The Red Cross is in talks to establish a so-called second chance school, which offers general education and vocational training to young people who dropped out of school without any qualifications.

The centre could provide training for people working in kitchens, care jobs, administration, forest management and landscaping, Schmit said. And it would fulfil Aline Mayrisch’s wish for the château to be a place for young people, too.

European heritage

In the meantime, the Red Cross rents the castle out as a location to film production companies. The money helps fund its upkeep. “The Red Cross does not to use donations to renovate the castle,” Schmit said. “When someone donates money to the Red Cross, it is dedicated to benefitting vulnerable persons and not to renovate a castle.”

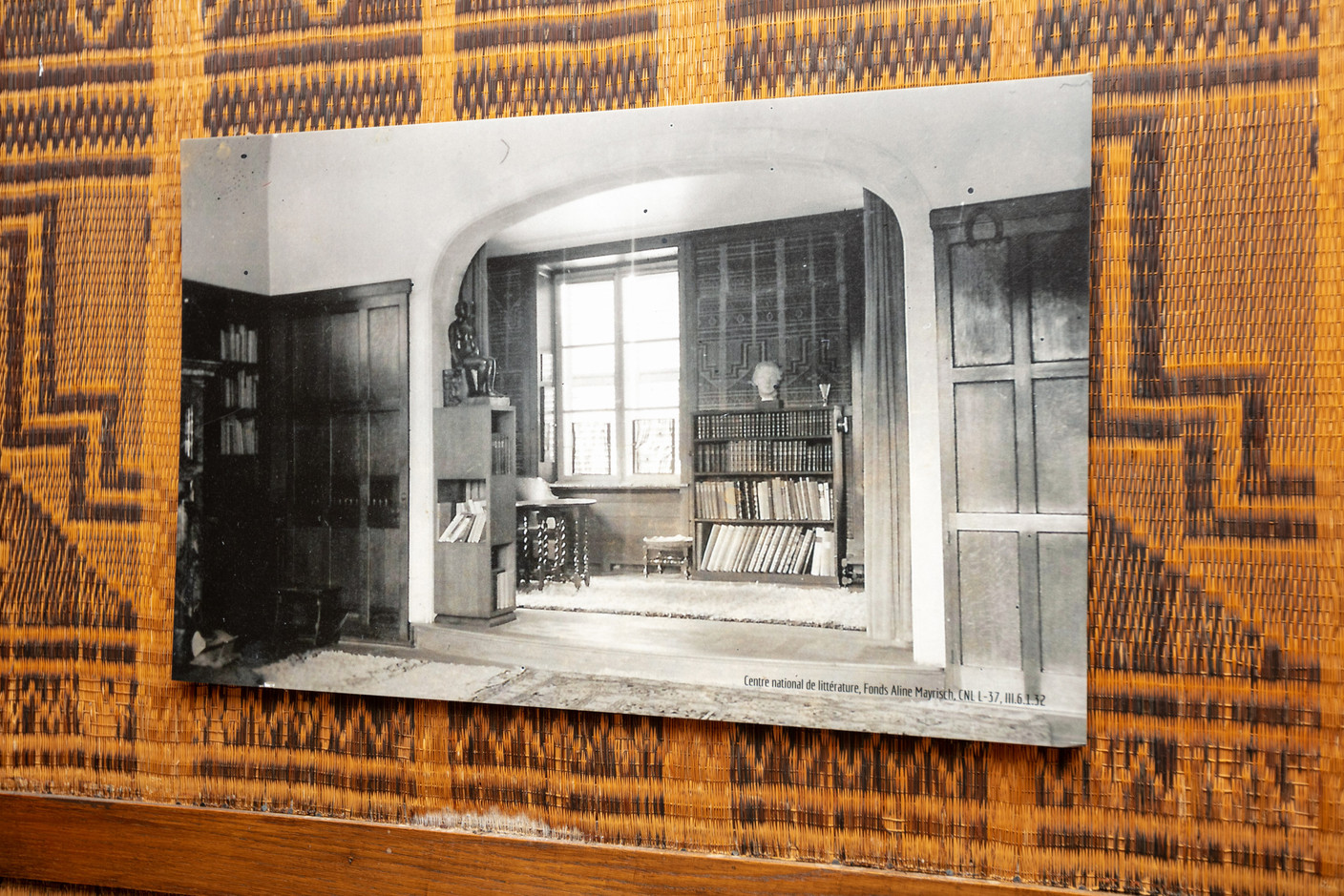

Among Schmit’s favourite rooms in the château are its library, the smoking room--wood panelled and with a magnificent view of the gardens--and the so-called blue room. French author and Nobel prize winner André Gide stayed in this room when visiting the Mayrischs. He was a family friend.

“It’s a historic site for Luxembourg and indeed for Europe,” said Schmit, not only because of the Mayrisch’s love for art and culture. Emile Mayrisch in the 1920s led the creation of a steel union--the “Entente internationale de l’Acier”--between Germany, France, Belgium and Luxembourg, a precursor of the European Coal and Steel Community. The Entente would collapse with the 1929 economic crash and advent of the Second World War.

Mayrisch in 1926 also helped found the “Comité franco-allemand d’information et de documentation” at his castle in Colpach, an organisation with offices in Paris and Berlin aimed at fighting misinformation and furthering friendship between both countries in the wake of WW1.

Global art collection

An art historian who lives near the château, Patricia De Zwaef, helped the Red Cross assess the collection it inherited with the building. Mayrisch accumulated an impressive array of works during his lifetime, some of which passed down in the family. Others have been sold over the years.

Edouard Vuillard’s “Félix Vallotton in His Studio” (1900), for example, is on display at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris while the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York owns the painter’s “The Album” (1895).

Valuable items, also including books, have been preserved with the help of the national museum of art and history (MNHA). Some furniture of the era remains in the building. A series of sculptures is scattered around the castle gardens, which are open for visitors.

Refurbishing the site won’t be an easy task as the building will have to respond to contemporary needs, such as wheelchair accessibility, while complying with monument protection rules. “It’s quite complex,” said Schmit, who hopes that plans for the château to be filled with new life will come to fruition soon. “I have fallen in love with this place,” he said.