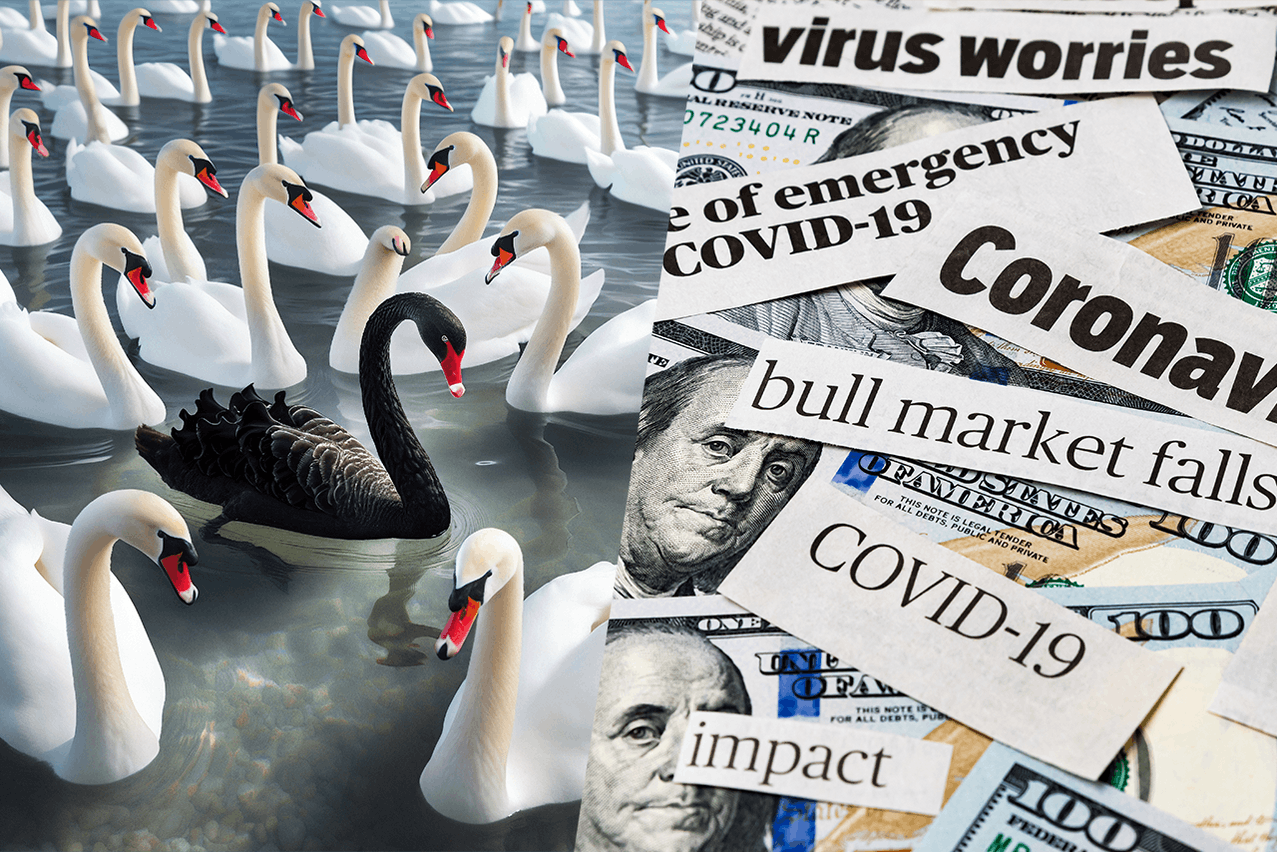

“I’m actually not a fan of the term ‘black swans’ because most extreme events are highly predictable and have very clear underlying causes,” argued Jón Danielsson, director in the Systemic Risk Centre of the department of finance at the London School of Economics. He explained that systemic events are enormously costly--costing Europe trillions of euros--and can be internal (such as the Global Financial Crisis of 2008) or external. On the latter, he suggested that “covid didn't quite get to the systemic level.”

John Berrigan, director general at the European Commission, agreed that the 2008 crisis might not have been a true black swan event, which--by definition--should be unpredictable. He thinks that the GFC was the result of endogenous risks that were observable and are now better managed.

“Even covid was not unpredictable. It had been predicted that we would face that kind of pandemic shock in the near future,” said Nicolas Veron, senior fellow at Bruegel and at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Some black swans are unfamiliar. “That’s why reading history is so important, because our personal, collective family memories only go back so far.”

Excessive focus of stability frameworks based on the GFC neglects new threats

Danielsson identified five threats. First, populism, as well as enlarged mandates that include climate change, are eroding central bank credibility. “Central banks have political capital, but it is finite.”

Second, rising debt levels potentially leading to a sovereign debt crisis. He explained that the death debt spiral is when a government gets into a state where it must borrow more and more only to service debt and provide public services. “If you want to look for a catalyst, my money is on Italy.”

Third, some countries, such as China, are deflecting criticism regarding poor economic performance and a slow-motion real estate crisis by manufacturing geopolitical tensions over Taiwan.

Fourth, Danielsson is concerned about the speed of crisis reactions, which may be amplified by AI in financial institutions. “AI is a rational maximising agent.” He thinks that AI tools at banks may have a significant role in their liquidity management. “If the private sector AI concludes that the public sector is not prepared--and I suspect it’s not--that endogenously makes an AI-induced systemic crisis significantly likely.”

Danielson’s fifth threat is the erosion of the global order, which increases systemic risk. This implies a weakening of the international framework meant to protect against crises.

Berrigan believes that post-crisis reforms have decreased endogenous risks in the banking system. However, he admitted that exogenous risks are now more complex and challenging, such as demographic pressures, climate change, technical disruption, war, geopolitical risks and a change in US engagement in the international order. “Our ability to manage [these risks] through the macroeconomic toolbox is probably less now than it was in 2008… as we are more fiscally stretched,” he said.

NBFIs: feeling better in darkness

Berrigan highlighted the growth of the non-banking financial sector and the need to better understand banks’ exposures to it. He noted a shift in the risk from banks to non-banking financial institutions (NBFI), a phenomenon that started in 2008-2009. “That side of the market has grown massively in terms of value and volume… much bigger than we expected.”

Berrigan argued that NBFI risk should not be disregarded, as some of the risk is back on the banking sector. “We think we have transferred the risk out, but we have not.” Veron warned that we should be wary of banks lobbying that “banks [are] good, non-banks [are] bad.” He reminded the audience that central banks and the financial stability community warned, at a financial stability conference in 2006 or 2007, that the next crisis would come from private equity and hedge funds. “It’s very important that the commission is able to resist the pressure from banks.”

“The largest NBFIs--the hedge funds and so on--often sit elsewhere in the world, making data sharing challenging,” stated Holthausen. Veron noted positively that since 2010, the Financial Stability Board coordinates to ensure that derivative transactions are reported in trade repositories. “In theory, we have the ability to have an informed judgment on where the exposures are,” said Veron. Yet, he remarked that the effort has failed for lack of coordination across jurisdictions and inside the EU. He called for a more open debate on how to fix this policy failure to gain a holistic understanding of systemic exposures.