“My flip-flops were now definitely ruined, so I looked for some pieces of wood to sew myself a new pair.”

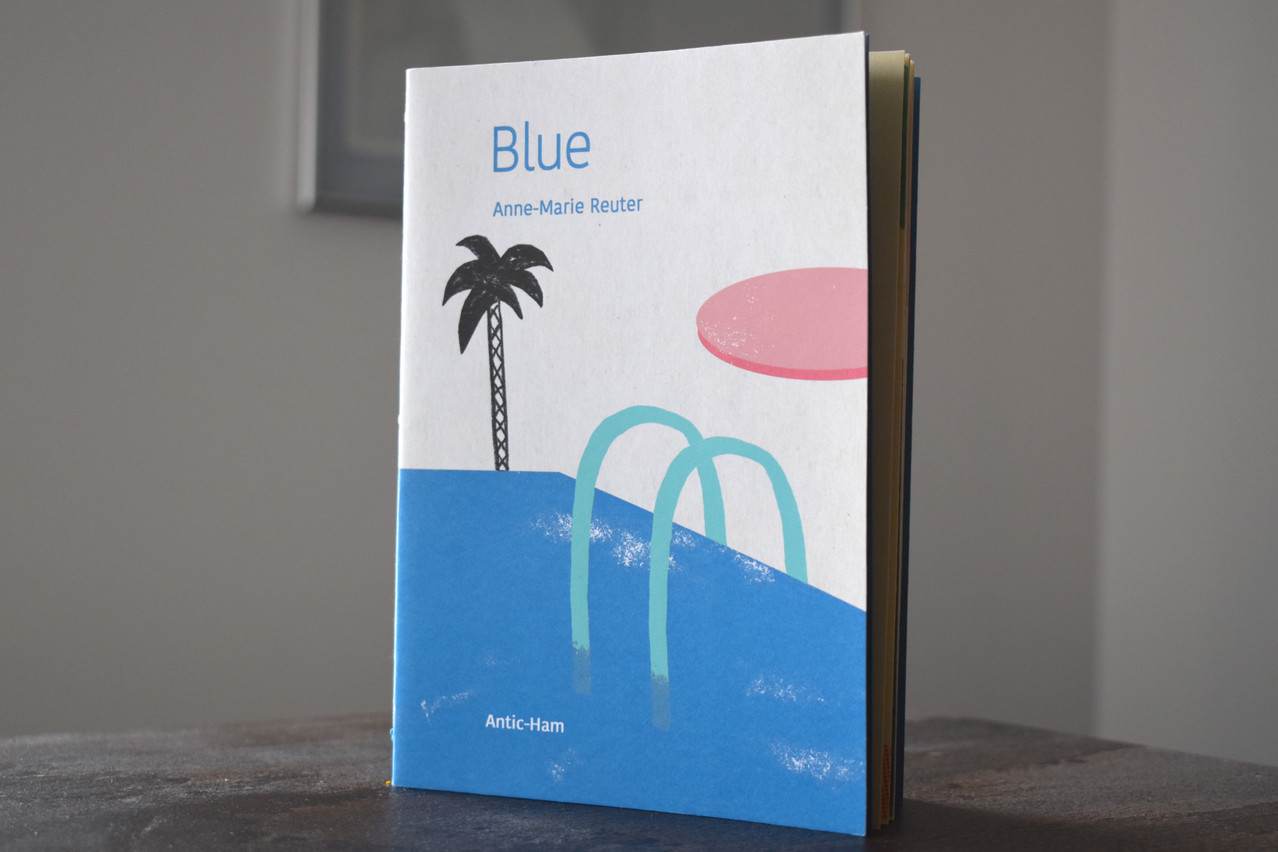

Deadpan blips in lexicography like the above make “” (2021), published by Redfoxpress and illustrated by Antic Ham, into a kind of infinity puzzle. Readers will naturally want to join up meanings between words and sentences, but will be denied just often enough to force the mind to fling its arms out and grapple for purchase.

Is whatever it finds the meaning of the story?

A heading at the start of the tale—“between the words”—might present a comment on that question.

Dynamic over relationship; outline over picture

The story does, however, have enough bones to form a shape. Together with friends Virginia and Anna, who—depending on the verb tense of the moment—are or are not currently there, a narrator recounts a story of hiking in the woods. The trio are joined by two bag-carrying figures named Len and Siggy (the latter sounding rather like a wink to Luxembourgers), and together the party braves the elements.

Soon, they encounter a bizarre birdlike beast. This “bird girl” catalyses a number of effects, such as Anna’s ability to understand it or Virginia’s knowledge of its movements, that give Reuter an excuse to playfully suggest ways in which the three main characters might relate to each other. Because, indeed, the narrator is unable to comprehend the bird girl in the same way. Virginia and Anna variously feel like parts of the narrator’s brain that have perhaps become detached, bygone figures who have a strong presence in the narrator’s memory, entities in the books being carried on the hike, or perhaps characters being written on-the-fly by the narrator.

In my reading, the narrator thus inhabits a double role: one whose authority is subverted by the superior knowledge of Anna and Virginia; and one who simultaneously has some kind of dominion over these same friends. Via this dynamic, Reuter seems to investigate consciousness by dissolving the wall between foreknowledge and discovery. She asks: can a mind not have more than one voice?

“In the sweltering heat of the snow”

Meanings in “Blue” don’t always join up in conventional ways (see the above subheader), a technique by which Reuter masterfully creates space for other patterns of meaning. The pages-apart introductions of Virginia and Anne, for example, employ a parallelism so cheerfully obvious that the friends momentarily sound like two drafts of the same entity.

Another such pattern is the recurrence of the titular blue, which appears on Virginia’s bikini top, the snow and Virginia’s face; but also as a language, and an important one in the narrator’s world. The idea of blue also enters into dialogue with the anomalous bird girl, who to the narrator is transparent and without colour at all. Only via Anna and Virginia does the bird girl gain a sense of colour.

One senses less that these patterns have a secret meaning for readers to uncover and more that they are picking up the lexicographical slack, offering an alternative method by which to parse the universe.

Ultimately

The story builds on certain surreal elements recognisable in Reuter’s debut publication On the Edge (Black Fountain Press, 2017), but presents a newfound loosening of structure. There is no gimmick or pindownable premise to “Blue” other than its continual suspension of meaning via language trickery, which it maintains evenly and wonderfully throughout. It’s a story that begs to be thought about.

“Blue” will be available at the Walfer Bicherdeeg book fair this weekend (20–21 November), as will works published by Black Fountain Press.