Born in 1965, Carine Krecké has been working for over six years on this research project, which she will be presenting in Arles from July. And she came very close to “Perdre le nord” (losing the north), which is the title she has chosen for the resulting exhibition, to be held in the Chapelle de la Charité in Arles as part of the Rencontres de la Photographie 2025. As the , this gave her the opportunity to exhibit at the Rencontres d’Arles. Her starting point? An investigation she began in 2018 into the war in Syria, following the accidental discovery of a series of photos on Google Maps showing the destruction of Arbin, a town in the northeastern suburbs of Damascus. And this is the question she asks herself: “How do we perceive war?”

Satellite images and social networks

Krecké has long been interested in the question of archives, satellite images, traces of power and mass surveillance. She readily appropriates open-source data and geospatial intelligence to produce documentary and literary works that blur the boundaries between reality and fiction.

“We are inundated with images on a daily basis, all the time, and we only perceive war from our screens,” says Krecké. “We receive a constant stream of images of gutted houses, bombed-out towns, groups of refugees fleeing their homelands... It’s all chaos and suffering on a loop, and we end up indifferent to it. I’m also struck by the work of photojournalists, who do a fantastic job with great precision. But at the same time, I’m disturbed by this quest for the spectacular. You become resistant to these images and find yourself confronted with the trivialisation of violence. So I asked myself if it’s possible to see war differently, with a different perspective.”

She then chose, as she had done in other previous work, to study satellite maps. “What’s the right distance to look at war?” she wonders. “If you’re too far away, you don’t understand what you're seeing. But if you’re too close, that’s no good either, because you become too involved. I visited Syria through satellite images. You can see the pulverised cities and the extent of the destruction. There are also more deserted areas in the northeast where some strange shapes appear from the sky. These are territories that have been under the yoke of the Islamic State. These images are not easy to find, but with patience, you get there.”

Krecké also dives deep into official and social networks, exploring stories of tragic destinies--both collective and individual--and makes contact with Syrians. “Some Google Earth images are completed by blue dots,” she explains. “These dots are actually photos of places that have been posted by local users. I tried to get in touch with these people and succeeded thanks to social networks. I selected five or 10 people whose stories I kept and included in my work.”

An elaboration in good company

On 17 July, Krecké was contacted by Lët’z Arles, who announced that she had won the call for projects for participation 2025. That was the first shock. Then on 8 December, another shock came with the fall of Bachar al-Assad. “With the fall of the regime, I suddenly had a lot more freedom to share information, because there was less fear of reprisals for the people I was in contact with.”

But the enormous challenge--giving form to all this material collected over the years--remains. Although she began this investigation alone, Krecké was joined in the course of development by her twin sister, who is working on the project as a collaborator. “I’m a privileged witness to Carine’s research. I’ve seen how addictive, obsessive and also very frustrating her research has become,” says Elisabeth Krecké. “She has become something of an expert on this conflict, with a perfect knowledge of the terrain, without ever having set foot on it, but it’s a fragile knowledge, which is not academic.”

Krecké is also supported by Casino Luxembourg director Kevin Muhlen, who has been following the work of the Krecké sisters for many years. “I’m here as a guest curator. Together, we form a complementary team,” Muhlen points out.

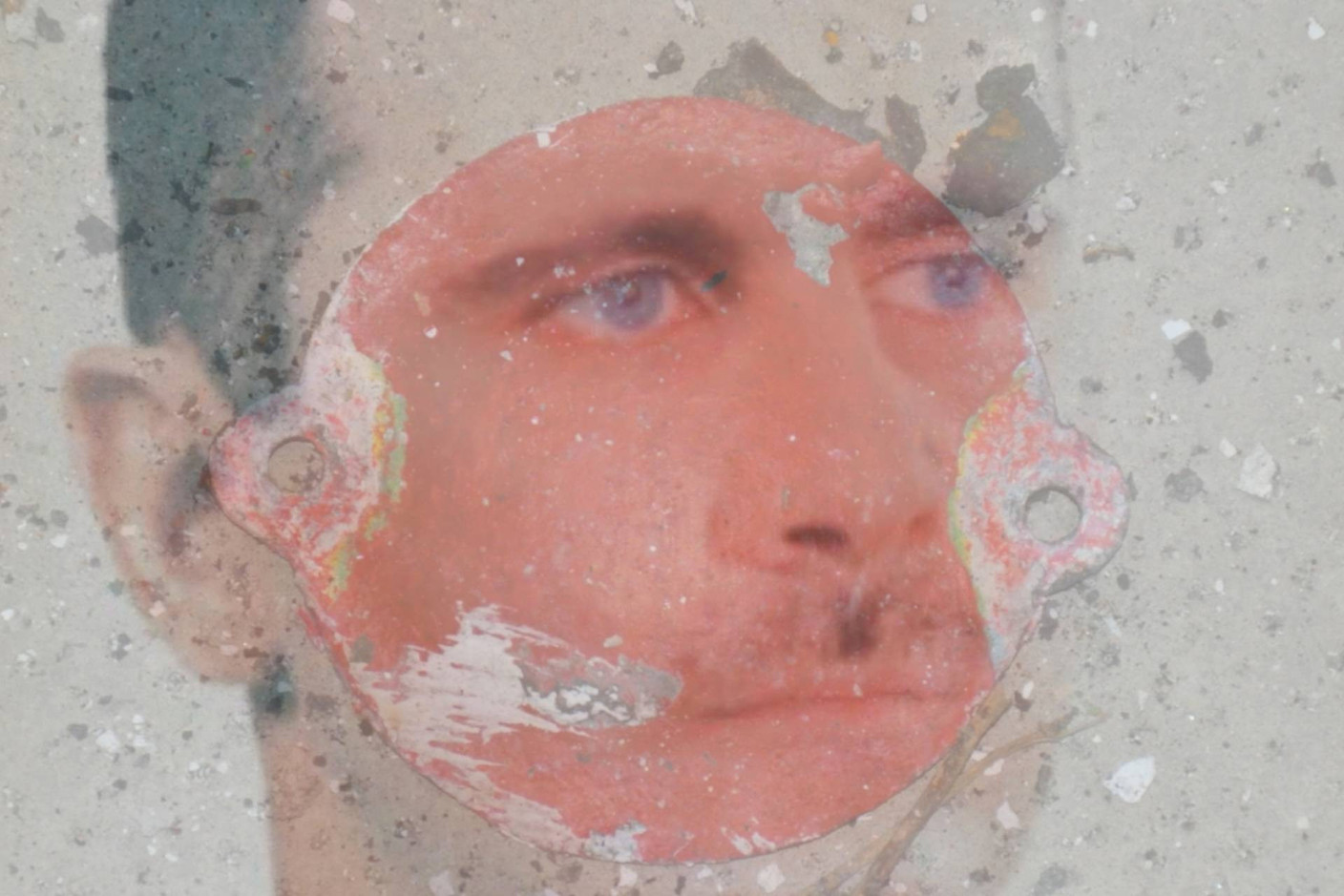

From all this investigation, Krecké retained images that she edited into a short film that she called “Too far, too close.” It explores war both from satellite photos and--on the other hand--images of exaggerated proximity, taken just a few centimetres from the subject. But surprisingly, these opposing views end up merging, blurring our reference points. She has also produced a series of videos entitled “Lend me your eyes,” which offer the point of view of protagonists in the field, without adopting a purely documentary approach. These videos will be shown in a set designed by Nico Steinmetz, creating a subtle balance between highlighting the videos and respecting the architecture of the baroque chapel. Added to this is a literary work, “The Yellow Men,” a fictional dialogue that “shifts the question of testimony to that of fabulation.”

The exhibition will be complemented by a publication, which will not be an exhibition catalogue but a real artist’s book. The exhibition will return to Luxembourg in 2027, where it will be on display at the Casino.

“Perdre le nord,” Chapelle de la Charité. From 7 July to 5 October as part of the .

This article was originally published in .