If you look carefully around Luxembourg, you’ll notice a peculiar subworld nested within it: a behatted cartoon mouse on a cooling tower in Differdange also turns up on a mural in the Glacis; a frog on a bicycle lurks in the village of Koler but also in Bettembourg…

This is the universe of “Mope”, street moniker of artist Alain Welter, whose playful illustrations have become increasingly ubiquitous in Luxembourg in recent years.

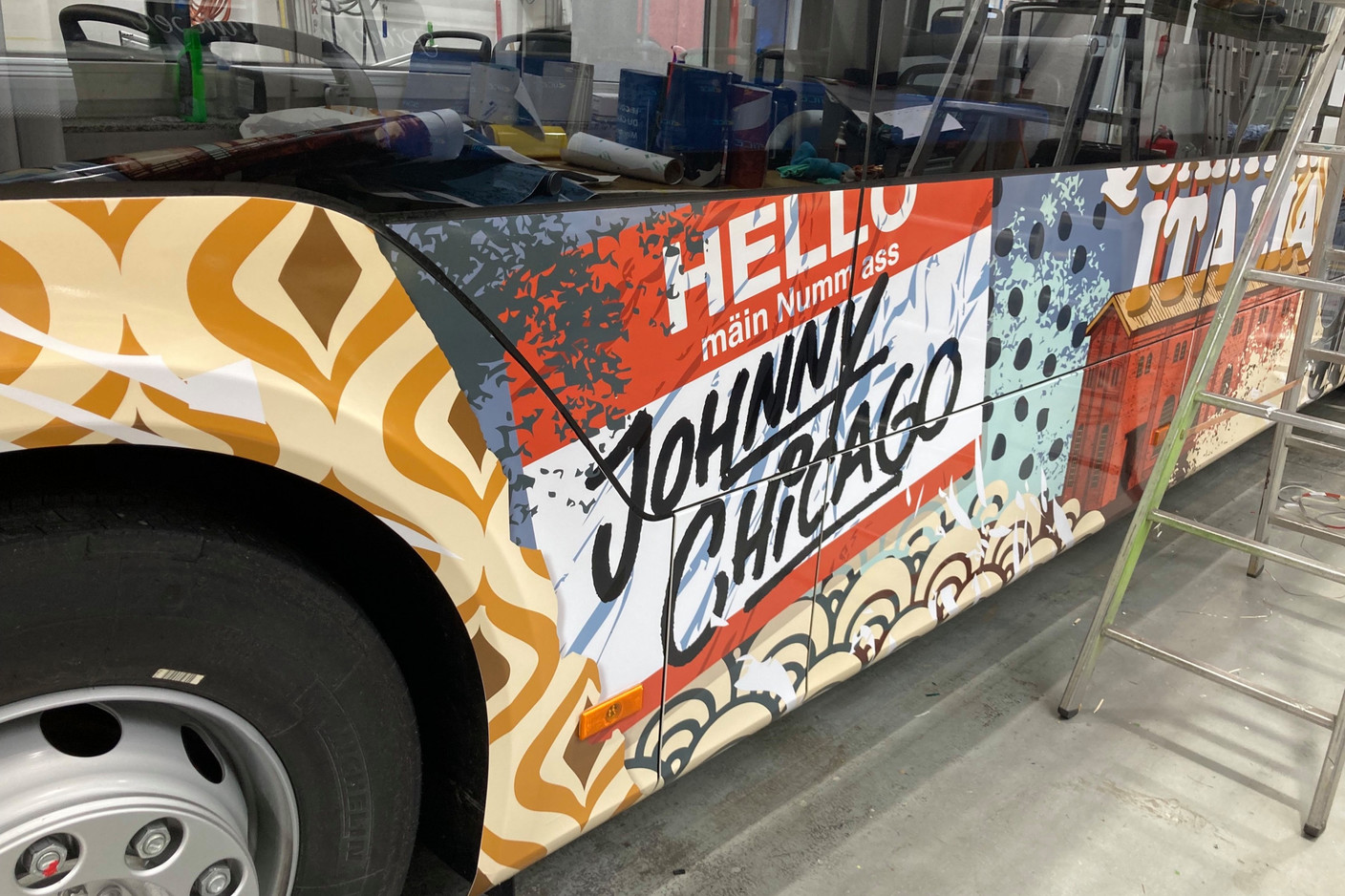

And now, for the first time, Welter’s familiar characters can move: as part of the Esch2022 cultural project, a special fleet of ten T.I.C.E. buses—the network running throughout the south of the country—have been outfitted with a special livery designed and drawn by the Luxembourgish artist.

Welter normally works with spray paint and/or acrylics, but for this project he used Photoshop and Illustrator. “I had a lot of difficulties,” he says. “I’m not used to that.” Photo: Alain Welter

The illustrations on the bus bring the culture of the Minett, Luxembourg’s southern region, into Welter’s colourful, stylised universe. Belval’s blast furnaces, the water tower in Dudelange, and other iconic pieces of landscape can be seen among his telltale cartoon characters.

Notably, the mouse—Welter’s alter ego, in fact—is on the back of the bus spray-painting the words “vun der Long op d’Zong” (literally “from the lung to the tongue” and meaning “to speak without a filter”), a slogan characterising people from the region. “It means that they’re very direct,” Welter says good-naturedly.

The bus also introduces a new character, a cat holding a pickaxe. “I’m quite happy with this one,” Welter admits. He’d proposed the same cat for an illustration commissioned by Bofferding, hoping to create another interproject link, but the client had wanted something else instead. So, the cat makes its debut alone on the T.I.C.E. bus. Given its unmistakable style, however, there is no doubting to which universe it belongs.

What is a “street artist”?

Welter uses spray paint and edificial canvases, but these things alone don’t make one a graffiti artist. People often get that wrong, he observes.

“I don’t like to put myself into one category, but I usually tell people I’m a mural artist and illustrator,” he explains. “I studied illustration. The bus is completely illustration and has nothing to do with graffiti or street art—and what I did in Koler [] is murals exclusively.”

“Sometimes I do graffiti, but only in my free time,” he adds.

Murals and graffiti share the same technique (the spray can), so what’s the difference?

“Graffiti is mostly just letters,” the artist explains. “And it has a spirit. It’s about making a statement against the system. Or about your ego: you’ll write your name as often as you can, and it’s about who is bigger and better than the others.”

Alain Welter (pictured) originally wanted to write “dope” as part of a project for the City of Luxembourg, which objected to the word’s drug connotations. He made a quick fix and became known as “Mope”, the serendipitous irony of which—he considers his persona to be the opposite of someone who mopes—pleases him greatly. Photo: Lynn Theisen

Unlawfulness is inherent in the graffiti spirit, which rose in the 1980s when street artists began writing their “tags” on public property, often by night and always without permission. Welter explains that in the ’90s this evolved into street art, which was more accessible to the public. By now, public illustrations aren’t even controversial anymore.

“One thing I’m often told, when people see me working, is: ‘Oh, this is art! What you see on the street, those tags… that’s not art.’ And mostly I respond: ‘Without people writing those tags I couldn’t do what I do now.’ So it’s been a whole process to come to this point.”

Welter’s murals are of course authorised, and increasingly commissioned. Past clients include Arcelor Mittal, the Post and the City of Luxembourg. It’s enough to live on, though he still makes time for his own projects, which he prefers. “Working for clients is what brings the money in, even if sometimes it’s not so fun,” he says, chuckling. “I’m happy that I can live from what I love to do. I can’t complain.”

And he has dabbled in true graffiti, he admits, though only passingly. “I was never really into the illegal graffiti scene,” he explains, “the main reason being that I’ve got my head a bit in the clouds… not very helpful if you want to do something illegal. The probability that I’d get caught by the police is pretty high.”

“I understand the spirit and what it means to go outside at night, to get an adrenaline kick,” he adds. “But on the other hand I prefer to take my time and make a nice image.”

World as canvas

Large outdoor projects engage the minds of the public in way that museum exhibitions cannot: Welter’s whimsies are part of our world in the most literal sense possible, and often confront us without warning in the natural course of our day. Some would see it as a downside, however, that this medium is more ephemeral than others.

But the illustrator seems unbothered by this. Indeed, he would much prefer his finished works to be altered by wind, weather and vandals than for their colour palates to be falsified by, say, an Instagram filter.

“I’m always happy when somebody reposts my work on Instagram,” he says. “But sometimes they put a filter over it and then… it’s not the same thing anymore.”

“But I really love to see how an outdoor painting changes over the years. It has a life of its own. And people even come and take it over… which, for me, is OK. That’s part of the game. You can’t have power over how it will evolve.”

However Mope’s world continues to grow and change, it is sure to continue tempting passersby into the depths of its parallel existence…

The “reading rat” and his bookworm sidekick can be found taking a literary adventure on an elementary school in Belgium. Photo: Alain Welter website

Watch the “making of” video of the Esch2022 T.I.C.E. bus project , or find out more about Alain Welter and his various projects .