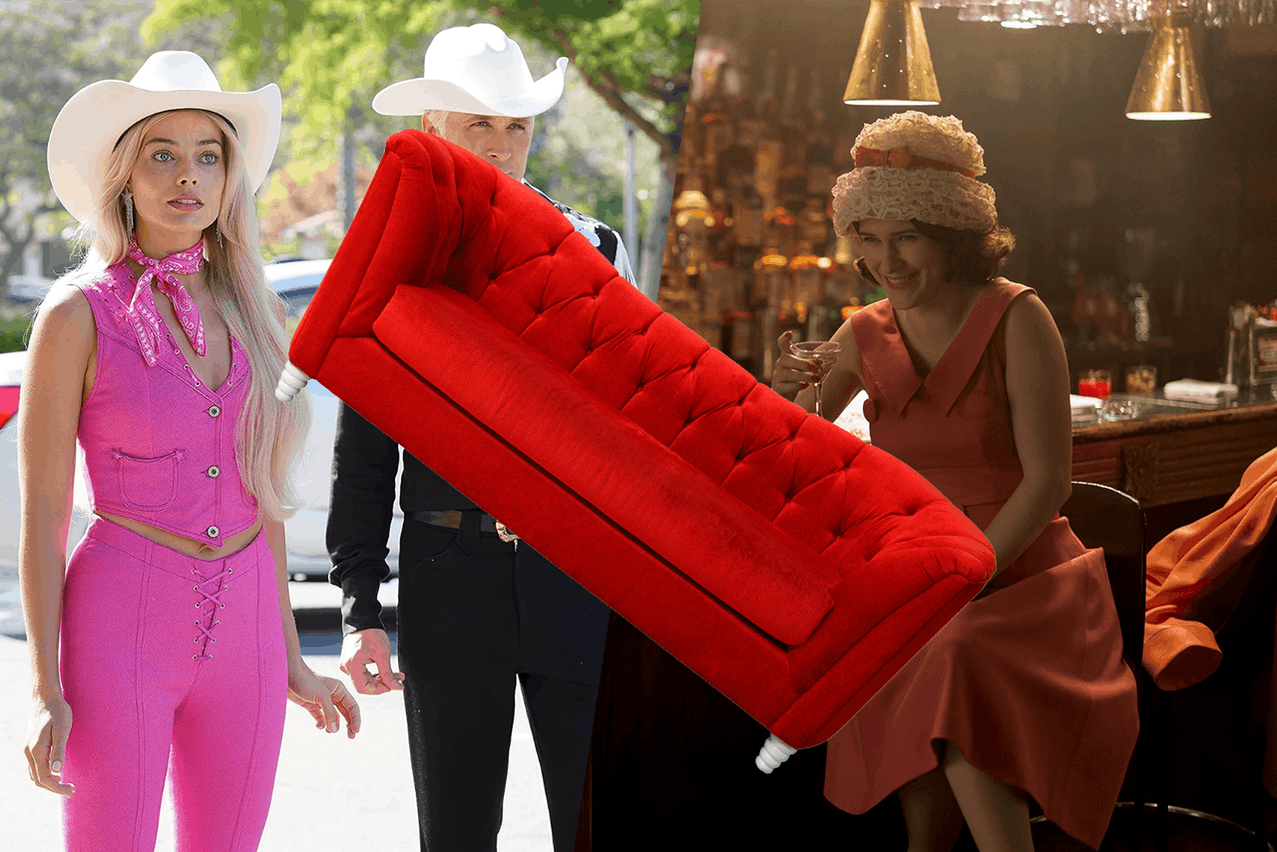

Welcome back to Delano’s movies and TV review column! Up this month: the Barbie movie and the TV series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.

(Last time, , we covered Succession, Killing Eve, Black Mirror, and Next Door.)

Barbie (2023)

Relevant to people who never had a Barbie? Inasmuch as the film is a blockbuster-grade, star-blasted work of modern feminism, it’s relevant to absolutely everybody. Having said that, it’s still a teen-friendly “message movie” and, at moments, breaks away from the story to address young women.

Reason to watch: You’re the last person who hasn’t seen it yet.

Other reason to watch: Ryan Gosling.

What does it mean--in the name of female empowerment and modern feminism and an eyeball-drowning deluge of the colour pink--for the Barbie movie to have been stolen by its male lead?

Actually, worse than that: a male lead playing a character who is the archetypical second-fiddler, whose raison d’être is to exist in the shadow of another, who is literally--literally--literally!--a Ken to a Barbie. I mean, it’s Ken!

Before we circle back to that, let’s take a step back. For the most part, Barbie plays like a message movie, i.e. one whose dramatic turns are, ultimately, designed not to further a plot but to create an environment ideal for delivering a message. In this case, the message comes via a handful of heartfelt speeches given by various female characters directly--or as good as directly--to the audience. As a vector for cinematically wrought meaning, this is a fairly clumsy methodology, but I will recuse myself from (further) judgment because the message is the movie and the movie is the message, which is obviously the point--yada yada yada, you wouldn’t criticise an apple for being unorangelike.

But there nevertheless is a story--the one that those speeches temporarily remove us from--and what fascinates about it is, naturally, the gender politics of its characters. Here is where the strength of Ryan Gosling’s performance paradoxically, if not vexingly, undermines his own character. Context: Ken lives in Barbieland where he has no identity beyond Barbie, so when he and Barbie travel to the real world he experiences, for the first time, a society that empowers him and favours his gender. Barbie, obviously, travels the inverse path, from utopia to--well--to the real world.

At this point, early on, it’s established that Margot Robbie’s performance as Barbie will be genuine: her character is asked to grapple with misogyny, recognise it, fight it, disempower it, ignore it, overcome it, obliterate it. She--actor as well as character--says what she means, because the metanarrative accommodates the truth that Robbie, being a woman who is alive, has also experienced sexism the way that Barbie does. As such, any power emanating from Robbie-Barbie comes from doubling down on that earnestness, i.e. the strongest way for her to embody the role is to insist, to implore, to be serious about the issues at hand and how to meet them.

Eventually returning to Barbieland to deal with its hostile takeover as Kendom (don’t ask; just see it), Barbie, newly equipped with modern ideals (cellulite is okay), can marshal the sisterhood--insert heartfelt speeches--in a wider bid for toy company Mattel to rebrand its iconic doll away from bimbohood and more towards independent-thinkerdom (though not before making a didactic pitstop with the Barbie inventor herself who, handily, is available to contextualise the original feminist purport of the toy).

And that’s that: Barbie is the movie’s protagonist and Ken its antagonist, though he and his army of Kens (don’t ask; just see it) are, compellingly, granted some emotional growth as well. Curtain falls; pink is awesome; gender wins.

However, for my money, Ryan Gosling fucks this whole thing up by delivering a hilarious performance that is utterly, preposterously ironic, and in so doing achieves what two hours of direct-hit Barbie truth bombs can’t even approach for her character: let the viewer look at him and assume the very, very best about him. Not see, but assume.

Indeed, Barbie’s tone acknowledges scepticism on the part of the viewer: this is my struggle, this is how I’m overcoming it. Its strength, as I suggested above, is in its earnestness. Metanarratively, however, Gosling is permitted to operate on a whole other level: he doesn’t have to insist on anything, teach us anything, clue us into his experience as a man; he can exaggerate the shit out of male cool-guy stereotypes and we know that he is making fun of himself. This layer of irony creates a far more complex space: whereas Robbie-Barbie says what she is, Gosling says what other people think Ken is, leaving us to imagine all that Gosling might be. For example: surely he’s not actually a beach rat who operates in monosyllables, so he must be clever; surely he’s not actually a raging misogynist, so he must be enlightened; etc. Gosling, via Ken, comes off as deep and sophisticated but in an awesome and effortless way. He--somehow--has nothing to prove. Robbie-Barbie comes off as determined and genuine, which is nice… but it means--somehow--that she has everything to prove.

None of this is to attempt to evaluate Robbie and Gosling as people. I only mean that the characters they play are surprisingly conservative, which results in a furthering of the status quo. Ken is funny; Barbie is not. His “struggle” is merely to understand himself; hers is to end all sexism. He assumes that people will believe the best of him no matter what; she assumes that people need to be convinced that her struggle is real. None of this, I think, is a shortcoming of the scriptwriters; rather, it’s the problem our society has, collectively and perpetually, with framing male and female personalities.

Anyway, in this sense, despite the well-constructed feminist messages hitting like freight trains, the movie ultimately doesn’t manage to test any new waters or get very paradigm-shifty. Its strength (besides eliciting some laughs) is more in problem presentation, or the clarity with which it summarises the feminist movement as it has existed in recent years. To be sure, if this invigorates and/or enlightens anybody then that’s a win. For a blockbuster, you wouldn’t expect any more. And for a blockbuster made by a toy company, you would actually expect far, far less.

The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel (2017-2023)

Type of show: Drama but, vibewise, a musical. (Elaboration below.)

The pitch: When her husband leaves her, Midge Maisel turns to stand-up comedy to complain about her life and then to build a career as a comedian. Also, it’s the 1950s.

Reason to watch: Humour. The show appears to be many things--a reflection on feminism, a manifesto for inclusion, a fun old plot--but, ultimately, fails in all of them. Safe passage through the five seasons is only possible if you (I didn’t) find it too funny to care.

Some--but certainly not all--of the frustrating symptoms of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel are treatable with an inoculation of, bizarrely enough, musical theatre. Indeed, a preexisting soft spot for the colour-by-numbers simplicity of song-based plot will likely ease the pain of watching characters who spend each scene revelling in the present moment of that scene instead of using the time to advance their lives, the way a human being might--or to advance the story, the way a character in a TV show might.

Because they do neither. (Nor, mercifully, do they sing.) Instead they engage in bits, improv-style but scripted comedic bits.

This narrative methodology has a (lack of) internal story-logic similar to that which makes people in musicals break into song, an energy whose origination point is discomfitingly external to the story-world. As such, what you’re watching isn’t really a “drama.” Yes, characters are taken on serious multi-episode story arcs, but each scene is, itself, its own comedy bit. To viewers, these play out like riffs on a lone and annoyingly transparent one-line direction: “In this scene you keep consulting a book for advice but the advice is always bad!” or “In this scene, the second you hang up the phone it rings again!” etc.

Never mind all that, though. I’m willing to accept, in the spirit of cup-of-teaism, that some people might consider that it works, that the relative thinness of the story is forgiven by the hilarity of these bits, the way (I can only assume) an attachment to a tappy-dancy number in a musical can make you not care that what it’s replacing is the details of the plot, the actual meat of the story.

Regardless, however, this narrative makeup does mean that the show must be cute instead of deep, which isn’t (necessarily) a bad tradeoff, except there is a problem: it nevertheless tries very hard to be deep--even profound--a mission screwed over by this comedy-bit-based structure, which again and again undercuts the dramatic and political points that the writers keep, inexplicably, setting up.

But it gets even messier: the drama and the politics--while each trying to take centre stage over the comedy in a way that dooms all three--are both a little haywire in the first place.

Politicswise, the writers seek to promote our modern understandings of feminism, race, sexuality, class, etc., and have therefore teleported many of the characters--all the good, virtuous ones, which was a very boring move on their part--in directly from 2017. But they don’t quite know why they’re doing it, other than (seemingly) to virtue-signal mainstream liberal American values, and you eventually notice that the environment flexes along with the needs of certain characters and their individual expressions of “wokeism.” When convenient for the message, the environment will be hostile: a club booker rejects Midge because she’s a woman; the potential exposure of somebody’s homosexuality threatens their whole career; an audience being chiefly black forces last-minute alterations to Midge’s act; etc. But at other times, the environment facilitates a disorientingly inclusive culture: a black writer is “one of the guys” at an otherwise white newspaper bullpen; a white guy dates a Chinese woman without a wisecrack from his friends or even his father (who is only upset because she’s pregnant); audiences crack up at “daring” takes whose true social context won’t arrive for some 70 years; etc.

What results is a 1950s that is incredibly unstable: the decade exists as a kind of nothing land with no identity of its own except as a likely place to find racists and homophobes and misogynists, ideal figures against whom our heroes can prove, again and again, their good values. Granted, the point of a period setting needn’t (at all) be stark authenticity, but building the setting itself around values foreign to it manages, chiefly, to never let the viewer forget that the heroes are figures of didacticism and not, really, characters capable of story arcs.

Which is why--dramawise--the mission of giving them longterm story arcs is so painful to watch. How, indeed, can you build a plot in such a setting? The macrostory concerns Midge’s comedy career taking off, but the individual steps along the way are distracted twice over: once by the comedy bits bleeding each scene, once by the relative unreliability of the environment in which these concrete actions are meant to be happening. In later seasons, the show gets a little desperate about its inability to advance the plot and starts jumping around in time, first a little, then a lot, to suggest that stuff is happening off-screen. That stuff happening off-screen, by the way, is exactly what fans of plot--and the show hits plot hard!--might like to have seen, but, well, never mind. (Season five in particular gets super, super weird about this.)

Anyway, I too have much to answer for, having sat through all 43 episodes of the show. I have no explanation for that. I make as little sense as the show does. Having done so, however, I can suggest that your only viable way through the whole thing is to find each scene funny by itself. Abandon the story. Abandon the message. If anything can tie it together, it’ll be the comedy… like music in a musical.