When a future researcher compiles a list of sayings of US presidents, this one from Donald Trump in April 2020 about using bleach as a possible treatment for coronavirus will surely make the cut: “Is there a way we can do something, by an injection inside or almost a cleaning?” Trump’s words prompted panicky warnings from bleach manufacturers to people not to drink their product and a spike in phone calls to help lines.

Press outlets leapt to describe Trump as a “mountebank – an itinerant quack doctor parading his wares from a platform (in Italian classic comic theatre, or Commedia Dell’Arte, the character is typically called Charlatano). In Ben Jonson’s 1606 comedy, Volpone, the eponymous hero dresses as Scoto of Mantua, purveyor of Scoto’s Oil. The original "snake oil”, it’s more expensive than bleach but neither harmful nor, indeed, beneficial if ingested.

Perhaps the comparison is unfair. Trump has simply joined the long line of those who, desperately seeking real cures, have found fakes. In Athens in 430BC, an epidemic struck. The air was thought to be diseased and in need of cleansing. The ancient Greek “father of medicine” Hippocrates himself is said to have come up with a solution – light bonfires, throw herbs and spices on them, and wait for the infection to pass.

Two thousand years later, bonfires were still in fashion. At the onset of the Great Plague in 1665, the College of Physicians pronounced that:

"Fires made in the Streets, and often with Stink-Pots, and good Fires kept in and about the Houses of such as are visited … may correct the infectious Air."

The college added that the “frequent discharging of Guns” would have the same effect – something that might appeal to the US president’s more ardent supporters.

But in 1665, not everyone could agree on what to burn. Should it be coal or wood? If wood, was it better to burn a more aromatic variety such as cedar or fir? The author of Golgotha (identified only as J.V.), one of a large number of plague books published in 1665, denounced as “a costly mischief” the burning of “sweet-scented Pomanders”. That did not stop him from recommending instead “Wormwood, Hartshorn, Amber, Thime or Origany”.

But hang on. It was already a hot summer in 1665. Wouldn’t all those fires warm up the infected air and cause the plague particles to multiply? Not necessarily. There were two kinds of heat, according to the 1666 work Loimographia, by 17th-century apothecary William Boghurst. There was the fierce, dry sort generated by fires in chilly northern climates, and there was the soggy, exhausting sort you found in the tropics. The former was cleansing. The latter opened the pores and made you susceptible to infection (as well as lazy and deserving enslavement).

Smoke to your good health

If this all seems like the effusion of bad science and worse ideology, consider tobacco. Recently it was reported that smokers might be less prone to catching COVID-19 (although other evidence suggests smoking makes the disease worse).

The idea of tobacco as protective has a distinguished heritage. Another treatise of 1665 recommends tobacco as “a good Fume against pestilential and infected air”, said to be effective for “All Ages, all Sexes, all Constitutions, Young and Old … either by chewing in the leaf, or smoaking in the Pipe.” On June 7 1665, the diarist Samuel Pepys was so unnerved by the sight of an infected house that he bought “some roll-tobacco to smell and to chew, which took away my apprehension”. It would later be claimed that no tobacconist died during the Great Plague.

Like Trump – but without the benefit of modern science – the bonfire lighters and tobacco chewers grasped the shadow of reality. So did the professors of heat.

Fleas carry diseases including the plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Photo: Janice Haney Carr via Shutterstock

Since 1894 and the identification of the bacillus Yersinia pestis, we have known that bubonic plague was largely transmitted by fleas. Well, certain odours may deter some types of flea. And the bacillus can survive for up to a year given the right combination of warmth and humidity.

What about transmission? Physicians in 1665 struggled with distinct sets of symptoms and chances of survival. How was it that some people developed buboes over many days and had a 25% chance of recovery, while others without evident symptoms suddenly keeled over?

They named the cause “the fatal breath”. Pulmonary or pneumonic plague, we say now. It is caught like coronavirus or a common cold: the only form of the disease transmitted directly between people and is 95% deadly.

Still, it was not quite as lethal as some people imagined. Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year reports a stubbornly held belief. If a man so infected breathed on a hen, rotten eggs would follow. In really severe cases, the hen would just drop dead.

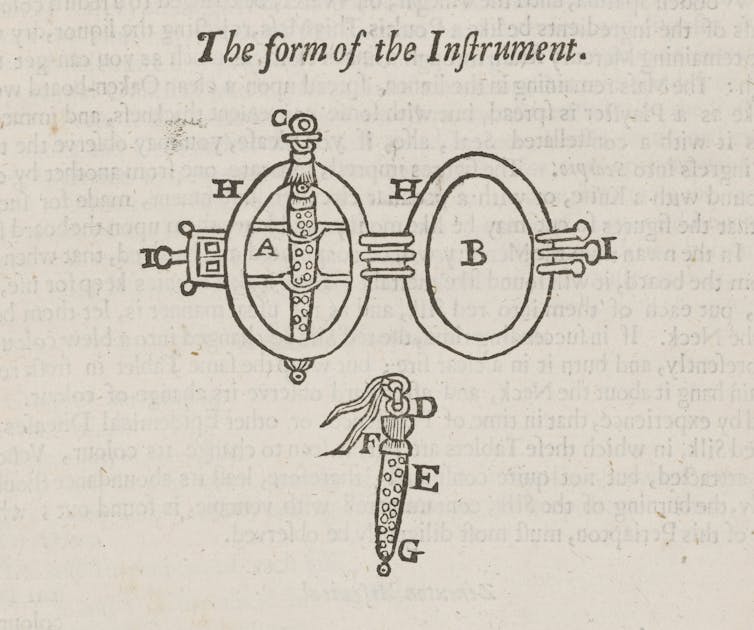

Design for an amulet to ward off the plague, 17th century. Photo: Wellcome Images, CC BY-NC-SA

The prize for bogus medicine, however, goes to the amulets and other trinkets people of 1665 carried to ward off the plague. Defoe dismisses them as “hellish Charms”, and claims they were often seen hanging round the necks of bodies in the dead carts. He captures their essence in a word the Oxford English Dictionary defines as “deceit, fraud, imposture, trickery”. The word? “Trumpery”.

![]()

David Roberts, Professor of English and National Teaching Fellow, Birmingham City University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.