With almost 50% of Luxembourg’s population hailing from abroad and an even bigger proportion of foreigners making up the workforce, Luxembourg has a rich seam of stories from outsiders making Luxembourg their home. These we read about, often in English, in expat publications like our own.

Much rarer, though, is the experience of the Luxembourger abroad or at home laid out in a language that outsiders might grasp. Probably, because you need to live away from your native country for a solid chunk of time to really be able to reflect on what it means to you. In the 53 years since he left Luxembourg for the US, poet and essayist Pierre Joris has had that luxury.

“Fox-trails, -tales & -trots”, the sixth book from Luxembourg English language publisher Black Fountain Press, is a distillation in vignettes and poetry of what it means to be a Luxembourger raised in the post-war period and a national identity filtered through the aquifers of distance and time.

Foxy tales

But don’t be fooled into thinking this is some fluffy foxy memoir. Like the nation it describes, at times the stories and poetry are contrary and shocking. Joris starts with the fox in the title, his totem animal which he has cherished since childhood when, seated on his grandmother’s lap, he first heard the charming morality tales from Michel Rodange’s epic the “Renert”.

He trails the fascinating origins of the fox theme through Indo-European medieval literature. To highlight the different rules for different times, he digs up the less charming “Retelling of the Story of Renart & the She Wolf”, a brutal rape story that was banned early on from the body of European fox tales, because of its explicitly sexual nature.

Foxes conjure different meanings for different readers. Having grown up in a rural, hunting village in the UK, I’m aware how foxes can polarise and fuel misunderstandings between town and countryfolk. As a migrant, what makes foxes relatable is their survival instinct, sniffing out food or work. For Joris, the writer, the appeal probably lies in Renert’s ability to convey so much complexity in a story.

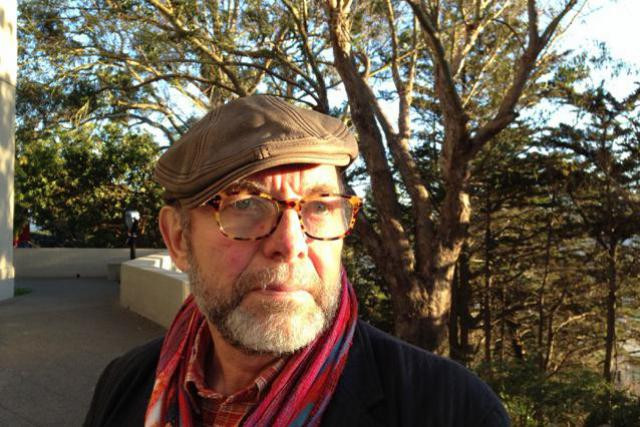

Joris' book is the sixth to be published by Black Fountain Press. Photo: Delano

Search for authenticity

I read hungrily the essays in the second part of his book. In “Moien”, Joris muses on being exiled by language and how his uncle, also called Pierre, who moved to France, never spoke Luxembourgish the same again. As foreigners, it is a language we know we should master if we are to shake off our otherness. But, is language really enough to overcome ultra-conservative attitudes to race and identity? In a candid memory of returning to Diekirch, Joris describes seeing children of colour playing in the street and makes an assumption which is turned on its head when he hears them shout at one another in local Luxembourgish dialect. “That’s when I knew there was still hope for the country, and that there would always be real Lëtzebuerger”.

This search for the authentic in Luxembourg culture beyond the picture postcard, often in the ugly and shocking, is the glue that binds the book. Joris alights on the hypocrisy in post-war attitudes towards the Germans and Americans, and in one matter-of-fact recollection shows the persistence of anti-semitism after the Nazi occupiers left Luxembourg.

I enjoyed Joris’ freeing memories of cycling, drawing parallels to a bird in flight. But, my favourite essay was “D’Plëss”, recounting how Place d’Armes in Luxembourg City became his retreat from bourgeois expectations and a place of self-discovery.

The son of a surgeon, Joris describes how he would later drop out of medical school and go on to become a bohemian writer, hanging out in other cafés. But, there was one line that jarred in this essay. Joris writes that his beloved Café Europe, which was the antithesis of bourgeois life, had been “long ago replaced by yet another horrible fast-food joint”. I don’t know if this hint of bourgeois snobbery creeping in was deliberate. Personally, I feel there is no more fitting foil to bourgeois culture than a fast food joint. One could argue, in a city like Luxembourg full of trendy bars, this is where the true bohemanians are found.

“Fox-trail, -tales & -trots” is on sale in most Luxembourg bookshops or purchased online via Black Fountain Press.