I arrived late at the church of Pauline Kael, becoming aware of the great critic’s work when I first studied film as an optional course at university in the early 1980s. I devoured “5001 nights at the Movies”, the book of collected reviews Kael had written for The New Yorker and which had just been published in England. And, having just watched the magnificent “Citizen Kane” for the first time as part of the course, I borrowed a copy of her essay “Raising Kane” from the university library and became even more obsessed with the making of the film that was for so many years rated as the greatest movie ever made.

In those pre-internet days when I moved to London I sought out copies of The New Yorker, which often arrived just in time for the release of the relevant film she had reviewed in the UK. Her reviews never made me skip going to see a film I had planned to watch, but I enjoyed her writing because she eschewed the film theory crap that many critics seemed to revel in because it made them look clever.

What I loved most about Kael’s writing was its fearlessness. She wrote from the heart with little if any regard for what others might think. Even when I disagreed with her verdict on a film, I admired her arguments. But together in the 1980s I found that we shared an admiration for everything from “Diner” (whose very theatrical release was down to Kael’s intervention, I later discovered) to “Brazil”, which Kael called “an original, bravura piece of moviemaking”, as well as the “cornpone-surreal quality and rambunctious charm” of “Raising Arizona”.

Kael wasn’t afraid to pan films against the general consensus of her contemporaries--she famously called “2001: A Space Odyssey” “monumentally unimaginative” and also had pops at films that I loved, including “Midnight Cowboy”, “Blade Runner” and “Vertigo”.

I discovered at an early age that it is best not to have heroes, because they will inevitably be a disappointment--no human is unflawed. So it is with Kael, who earned a reputation for being unnecessarily mean--and meanness for its own sake has no place in criticism or journalism. And at one stage she was accused of being homophobic, a charge against which New Yorker editor Craig Seligman vigorously defended her.

But her influence was monumental, not just on cinema writing but on film making itself. The great Roger Ebert wrote in his obituary of Kael that she “had a more positive influence on the climate for film in America than any other single person over the last three decades.” That is as good a tribute to a role model as anyone could wish for.

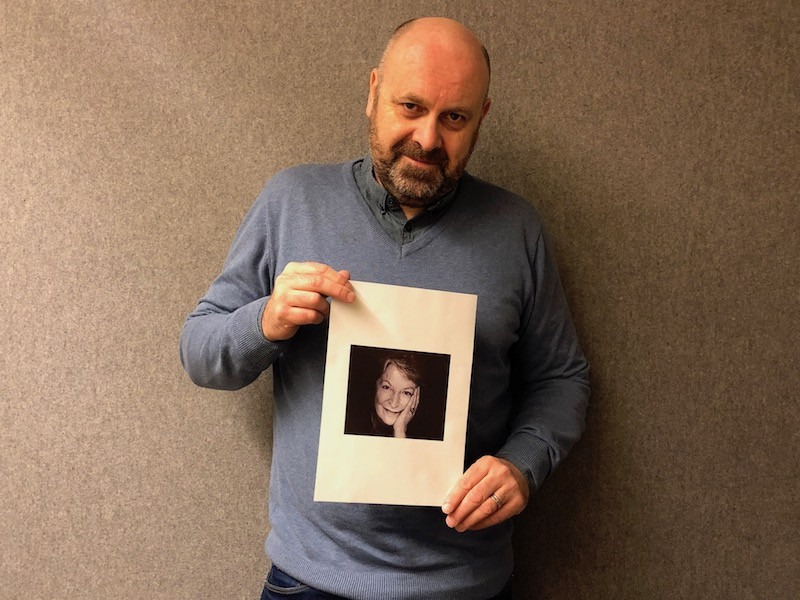

Do you have a woman in your life who has inspired you? In celebration of International Women’s Day, we want to hear from you. Send us a mail to [email protected] with your story and photo, or share your story on social media with the tag #myfemalerolemodel