The findings raise the prospect of being able to develop simple, non-surgical treatments for human wounds in the future.

Large skin wounds and ulcers are painful and occasionally life-threatening. When the surface of the skin is ruptured, epithelial cells, which make up the outer layer of the skin, migrate towards the wound in an effort to seal up the injury. But this healing process becomes more difficult in larger wounds and is impaired in older people, making the need for simple, effective treatments all the greater.

Now Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a scientist at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, and his colleagues have figured out a way to treat wounds from within, without the need for neighbouring epithelial cells to come to the rescue or for surgery.

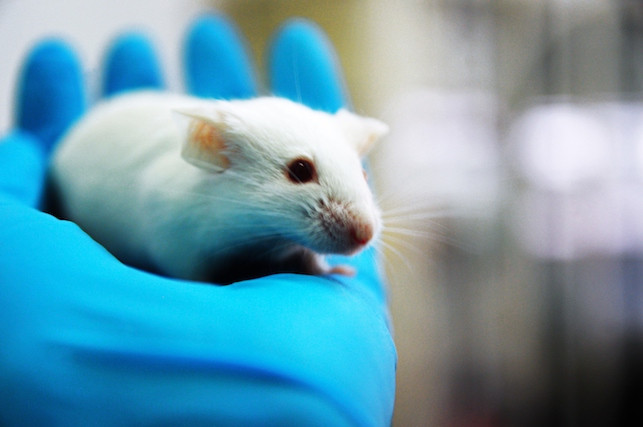

The researchers, whose work is published in the journal Nature, used a genetic technique called cellular reprogramming to alter the non-epithelial cells in the wounds.

They injected viruses into the cells of non-healing ulcers “to force the expression of four genes in these other [non-epithelial] skin cell types and turn them into epithelial cells,” said Izpisua Belmonte. The newly formed epithelial cells successfully healed the injuries in the mice over a period of 28 days or less.

Before any clinical applications can be realised the technology needs to be improved and tested for long-term safety, cautioned Izpisua Belmonte. But he is optimistic. "The current study is the beginning, and we believe that the timeframe for healing may be further shortened in the future,” he said.

If this technology could help treat chronic ulcers in humans, it could be a simpler and quicker solution than surgical skin transplants or artificial skin grafts.

It would work as a kind of gene therapy, said Izpisua Belmonte, with treatment delivered through “local introduction of viruses ... to reprogramme the cells within the wound or ulcer”.

“Currently, virus production is quite expensive, but cost should be less of an issue if we are able to scale up the production,” he said.

If successful in human skin, this repair method could also potentially be applied to other tissues and organs.

Kevin Gonzales, who studies wound healing at the Rockefeller University in New York and was not involved in the findings, said the work was promising but was “only the first step in the long journey to realisation of gene therapy for wound healing, as the authors acknowledge”.

“Nonetheless,” he said, “this breakthrough is a significant contribution to the field, as it will serve as the foundation for improving gene therapy and reprogramming techniques for the skin, as well as for finding chemical alternatives for chronic wound treatment.”

Anthea Lacchia