The Villa Pauly was built in 1923 by Luxembourg physician Norbert Pauly who had married the stepdaughter of a wealthy industrialist. Inspired by the architecture of medieval and Renaissance castles, the striking building bore witness to one of the grand duchy’s darkest chapters.

The German Wehrmacht in May 1940 invaded Luxembourg, initially placing the country under military administration and finally fully annexing it into the Nazi Reich. The Villa Pauly on Boulevard de la Pétrusse housed the Gestapo secret police until 1944, when the capital was liberated by Allied forces.

From its offices at the villa, the Gestapo organised the deportation of Jews from Luxembourg and inflicted torture, interrogation and other cruelties on the local population and resistance. The Gestapo also had satellite offices in Esch-sur-Alzette and Diekirch.

“A lot of the villa’s history hasn’t been worked through,” said Patrick Majerus, who leads the Service de la mémoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, a government office dedicated to WW2 remembrance. “There are a lot of myths surrounding this building.”

A team of historians has been charged with delving into documents and archives to uncover what is unknown and verify what has been handed down anecdotally. For example, prisoners were allegedly thrown down the building’s stairs, some breaking their necks in the process. In one story, a prisoner manages to catch their fall and run for escape.

Cells installed in the building’s basement were removed at some point after the war and evidence only survives in pictures. Generally, it’s unclear how the interior was altered over the years. “We know a lot has been changed,” said Majerus. Some features, such as the imposing staircase, wood panelling and fireplace in the entrance hall, however, have survived.

The Pauly family at the end of the 1920s fell into financial difficulty and began renting out their properties and even Pauly’s car. The family was reportedly out of the country when the Nazis invaded.

Around 3,500 Jews are thought to have lived in Luxembourg before the Second World War. More than 2,500 fled before the Nazi occupiers forbade migration in October 1941. Around 800 Jews were interned at the Cinqfontaines Abbey in Luxembourg’s north. More than 600 were deported.

The estimated number of Jews killed during the Holocaust ranges from 1,000 to 2,500, including those killed in Luxembourg, in Nazi camps or after deportation from France, where many had sought refuge.

Norbert Pauly never returned to his home. He died in 1952 and his heirs sold the villa to the Luxembourg state in 1960. It housed a variety of government office before a WW2 research centre moved in 2001.

The Service de la mémoire since June this year is consolidating its team at Villa Pauly. Previously, staff also had offices at the former Hollerich train station--from where Luxembourgers were deported during the war--and the ministry of state--under whose auspices the service operates.

Somewhat curiously, the Service des Ordres nationaux, which manages the bestowing of public service medals and other honours awarded by the state, forms part of the team at Villa Pauly as it is managed by Majerus.

Soul-searching and new life

“It was oppressive,” he said of his first visit before taking on the post at the helm of the department. “But we are working on bringing new life into the building.” The villa will become more accessible to the public in future. A first exhibition on deportations to the Litzmannstadt camp is planned for October.

Two rooms on the ground floor have been cleared to make room for future activities. Smaller commemorative associations have agreed to transfer most of their documents to the national archives and will work in a co-working space in the building.

There are also plans to work more closely with museums and schools. The department already cooperates with a centre for political education (Zentrum fir politesch Bildung) and the University of Luxembourg.

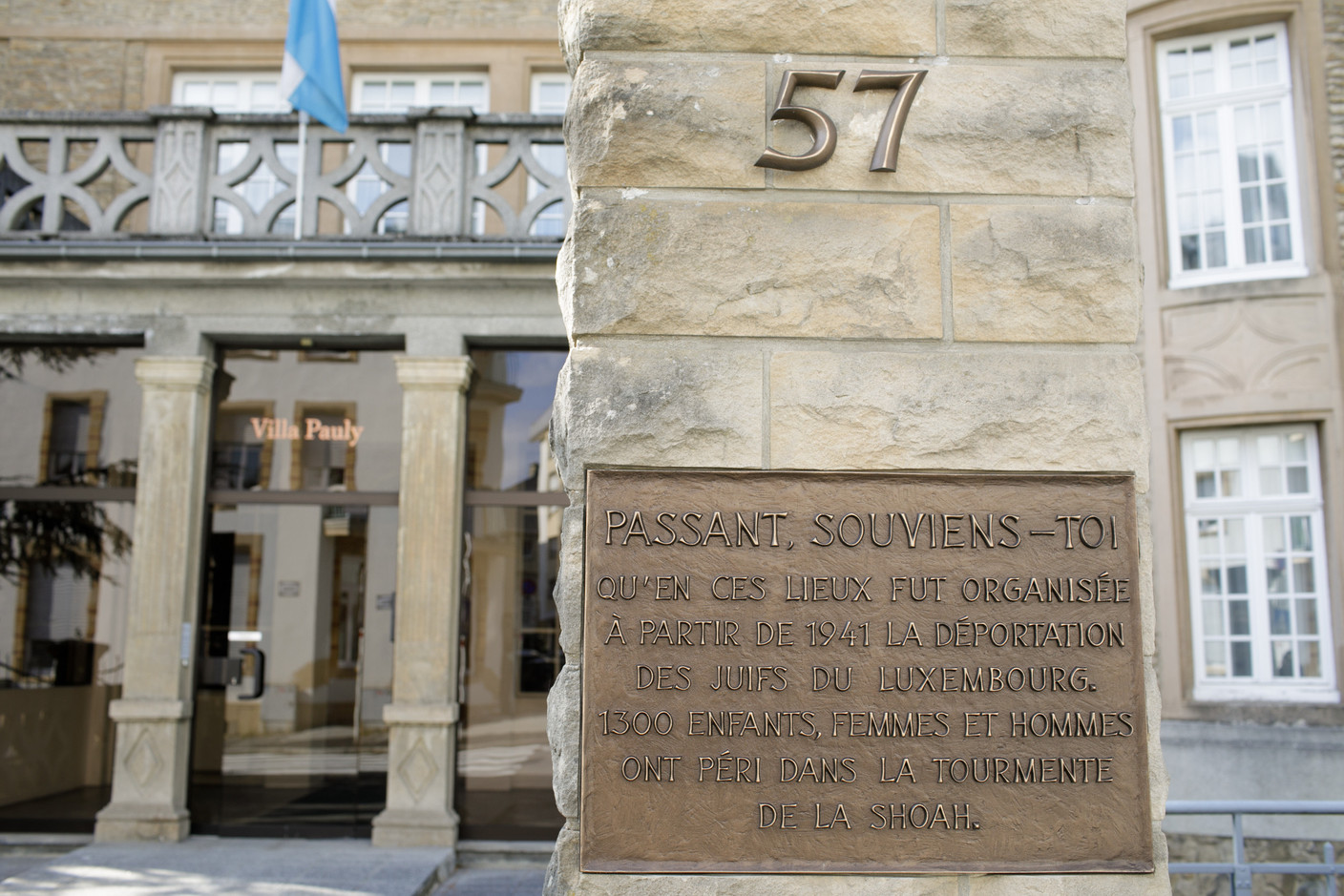

A plaque on the outside commemorates the Villa Pauly’s history as a Gestapo office since the 1980s but it wasn’t until 2016 that a second inscription was added to acknowledge that deportations were organised at the site. This came after a 2015 report found some Luxembourg authorities had collaborated with the Nazis, prompting a national soul-searching on the grand duchy’s WW2 past.

This continues today and only in January this year the government signed a with the Jewish Consistory, which includes the refurbishment of Cinqfontaines Abbey and turning it into a commemorative learning centre.

“We must respect history, but we must also create a building that people want to visit, that is lively and not only about the worst of what happened here,” Majerus said about the future of Villa Pauly.