We’re assembled at the Maison des Sciences Humaines on the University of Luxembourg’s Belval campus, three of us: media archaeologist Aleks Kolkowski, Maison Moderne photographer Matic Zorman, and me. Kolkowski leads us into the media lab, a large room with soft dark walls and crammed with high-end audio and video equipment.

But there is something else in the media lab, too: a His Master’s Voice (HMV) 2300 portable disc recorder from 1948, lately restored by Kolkowski. It weighs 60 kilos and looks to me like an oversized record player with some extra bits attached. We’re here for a demonstration of this device, which the researcher/musician has learnt to operate as part of his work at the Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C2DH).

First off, Kolkowski dons a working pair of headphones from the 1920s.

Unexpectedly, he next produces a hairdryer and aims it straight at the lacquer disc already fitted into the machine. This elicits an enthusiastic purr from Matic, who starts snapping photos immediately. “Because these discs are so old I’m actually going to heat it up,” explains Kolkowski over the hairdryer’s drone. “They get very dry and hard. So in order for a good recording, you really need to soften them; otherwise you get a lot of noise.”

What he plans to record is an old Luxembourgish radio transmission, part of a wider C2DH project, but these particularities don’t fuss Kolkowski too much. “Any opportunity I have to use the machine and get more experience with it is useful,” he says.

Kolkowski heating up the blank lacquer disc. Photo: Matic Zorman / Maison Moderne

Once the disc is sufficiently warm, he’s ready to begin.

During the short process—just three minutes to fill up the disc at 78 RPM—Kolkowski remains alert and active, even more so than the trigger-happy Matic. Indeed, rather than flicking a switch and sitting back, the media archaeologist monitors the spinning disc and artfully moves debris out of the way using a fine paintbrush.

This debris is “swarf” (known as “chip” in North America), the thread of material that’s cut out of the disc during the recording. Swarf is what’s responsible for many of the telltale blips and squeaks you hear in such old tracks, and presents a major annoyance to recording specialists.

“That’s the swarf,” he says afterwards, indicating a pile of fine black spaghetti. “The positive of sound.”

Hands-on history

Kolkowski’s research is part of the C2DH’s “” project, short for Doing Experimental Media Archaeology. This approach to history doesn’t limit itself to dates, statistics, names and documents, but seeks to understand technologies through actually using them. “We’re trying to find out about these technologies from the point of view of the user,” says Kolkowski. “It’s an investigation of the history of use, which is often hidden.”

Part of the process, he continues, is rediscovering the nuances of technologies that only users would notice. “There’s a whole choreography of movements that you have to do, repetitions and things like that,” he explains. “It’s about haptic, visual and aural perception.”

His background as a violinist proves helpful here, since operating certain old technologies draws on a bodily presence that is essential to musicianship but which modern devices rarely require. “It’s somatosensory,” he says of using the 1940s equipment. “It has to do with touch, pressure, movement, gesture… and these are also very important when you’re playing an instrument.”

“I’ve been thinking in terms of gesture,” he continues. “It’s kind of a form of sound writing. If you think of physical writing as a gesture, then it’s sort of a prosthetic form of writing.”

In a larger sense, his mission is to codify these bygone nuances and tacit skills in order to describe them in a publication due out later in 2022. Several contributors are working on the project, led by C2DH director Andreas Fickers. The end product will be a two-volume guide to experimental media archaeology: one volume for practice and one for theory. Kolkowski, clearly, is on the practice side.

Restoration versus replication

Another strand of the project involves the creation of replicas: recently Kolkowski has been working with University of Luxembourg engineering students on a stentorphone, a type of air-powered gramophone from around 1910.

“This was a strange technology,” he says, eager to dive into its historical context. “Just before the First World War they were amplifying sound using compressed air. That was before thermionic valve or electronic technology.” He describes it as a link between purely acoustic sound and electronic amplification.

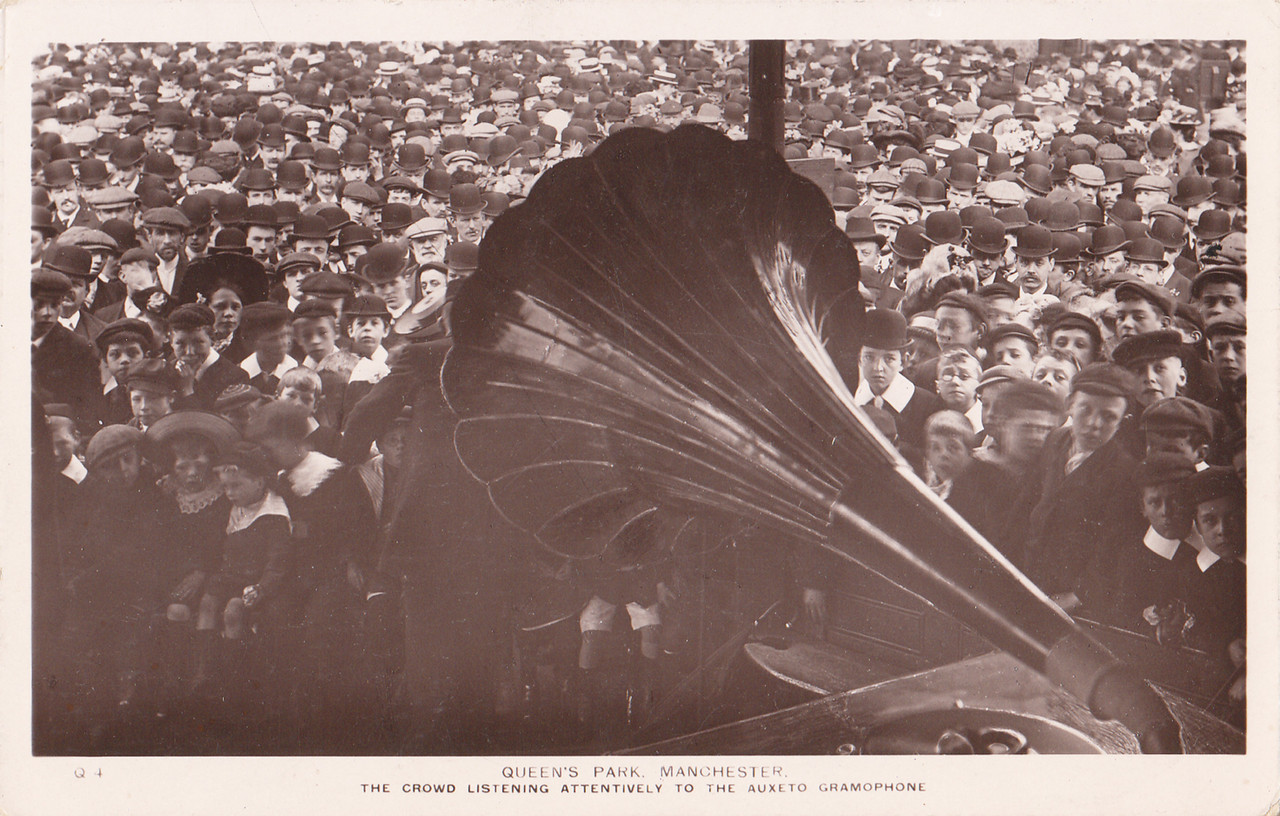

“Compressed air amplification introduced concerts of recorded music to the masses,” he explains. “They would play it in parks in bandstands. And it sort of coincided with the opening of municipal parks in the UK around 1907.” People would gather by the hundreds around the device as its operator, ancestor to all modern DJs, would spin opera arias or other music of the day.

This postcard (ca. 1906) depicts a crowd in Queen’s Park Manchester listening to an auxeto gramophone. Image courtesy of Patrick de Caluwé

The engineering students’ version was done with 3D printing and computer-aided design (CAD), using polymer and metal. “We made one that works and we restored an original,” says Kolkowski, “and we compared them. You learn an awful lot about the technology in that way.”

“Forget steampunk,” he adds. “These were really extraordinary technologies.”

Artistic output

While the DEMA project is centred on the forgotten skills needed to operate arcane technology, Kolkowski’s interests spread further than that—namely, into the creative realm. His PhD is in the creative uses of antiquated audio technologies and obsolete media and he has formerly been the composer-in-residence at the British Library Sound Archive. Thus, it’s no surprise that the HMV 2300 has also inspired him creatively.

“What I’ve also been doing,” he says, “is recording different [old] machines and making a montage composition just of the sound of the machines in operation—not of the music being recorded. So, for instance, the sounds of the swarf and of the switches, the clunky sounds of operating the controls, etc.”

“That’s another kind of output that I can do as a musician and researcher,” he continues. “It’s an alternative to reading a text—this way you can sense it, hear it, experience it, and not just through reading or your imagination.”

In fact, Kolkowski’s creative career predates his research activities: back in the 1990s he worked as a violinist in new and experiential genres. “A lot of my colleagues started experimenting with digital technology and laptops,” he says. “And this kind of stuff—instrumentalist with a laptop—was becoming completely ubiquitous. I wanted to do something different. So I went back to the beginning of sound reproduction technology and started using gramophones and phonographs.”

He describes replacing modern cables with bits of tubing, and sending his violin through horns instead of electrical amplifiers. “It was a parody in a way—my response to digital music making. But then it became a much more serious research interest.”

Kolkowski in 2000 playing a Stroh violin, a type of violin amplified by a built-in horn. Photo: “Portrait in Shellac” by Anja Fuchs

“Nowadays I collaborate a lot with electronic musicians,” he adds.

The past inside the present

Incorporating arcane recording technologies into modern works is not, in Kolkowski’s case, about nostalgia. The technologies are perfectly viable and workable, merely forgotten (or almost). His artwork is new and his methodologies present unique ways of soundmaking that have, he says, a potent ability to invoke memory.

“Early acoustic recording captures enough musical information to make it recognisable, as in who’s singing or what’s being played,” he says, “but it’s still very impressionistic. There’s a relationship to memory. You have to listen through this patina of noise… surface noise, age, distress—it’s a form of deep listening, a form of really trying to think back and remember.”

“So there’s a strong connection with memory that really has nothing to do with nostalgia,” he concludes.

In presenting audiences with these technologies, blended in modern ways and sometimes with modern equipment, Kolkowski’s work reincorporates a materiality that has largely been lost in modern recording. Sound philosopher Christophe Cox, in his book Sonic Flux, notes that records are exchangeable objects that “dissolve the distinction between musical and nonmusical sound”, i.e. by capturing sound and music together in a way that a musical score does not. The record is an object, a tangible commodity, that connects listeners to the place and context of its origins.

But modern music manages to eliminate most if not all evidence of unwanted sound, and has assumed an infinitely copyable digital form that no longer forms a strong relationship with place. “The mp3 accelerates the circulation and replication of audio recording,” the philosopher writes, “[…] rendering it as pure information that confounds the logic of scarcity on which commodification depends.”

In this world of music being unendingly sharable and copyable as “pure information”, Kolkowski’s usage of old technologies and their unintended sonic byproducts challenges audiences to rethink where sound comes from, while simultaneously entering into dialogue with modern forms of remixing and sound editing.

Audiences, Kolkowski reports, have generally reacted positively to his work. “There is a revival of interest in vinyl and physical sound objects,” he says.

Back in the 2000s, however, when more listeners were familiar with older technologies, his work wasn’t accepted quite as wholly. “I remember doing disc recording demonstrations in Berlin, and some of the older generation would come up and say: ‘What the hell are you doing this for? This stuff is obsolete!’”

Aged sound

“I’m going to play it back with a steel needle. It’s really destructive, but here we go.”

Back in the media lab, Kolkowski is poised to play back the recording. Matic and I watch him lower the needle onto the disc. Lo and behold, the radio broadcast comes back out in an authentically aged—except it isn’t aged—world of sound: the voices have gained a tinny quality and a few light scratches and squeaks are detectable from swarf interference.

“If you had a modern pickup,” Kolkowski says over the playback, “you’d get much more frequency out of it.” Pickups nowadays are made of diamond or sapphire.

We listen for another minute.

The recording is crisp and clear and expertly done. All the words are there… and yet you cannot listen to it without trying to disentangle the extra auditory signals: the particular timbre of the voices, the “old” quality of the noise. The audio track has become bound to this particular HMV 2300 disc recorder, to the university’s media lab, to this particular morning in Belval.

“You can get pretty decent recordings out of this machine, actually,” Kolkowski sums up.

He can, anyway.

Find out more about Dr Kolkowski’s or his work .