75 years ago, on 16 October 1946, the death sentences were carried out in the gymnasium on the grounds of Nuremberg prison against the defendants found guilty by the Allies as major war criminals. Only Hermann Göring escaped the gallows by committing suicide just a few hours before the execution.

It is hardly known that 13 of the 22 accused - among them Reichsmarschall Göring, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz and Wilhelm Keitel, the head of the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht - were interned and interrogated by the Americans in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg from May 1945.

The secret prison in the spa town of Bad Mondorf was given the code name Ashcan (bin). Why Bad Mondorf was chosen is not clear. Luxembourg had been liberated twice by American forces with heavy losses. The Allies could therefore rely on a population and government that were well-disposed towards them. Moreover, Bad Mondorf was within reach of General Eisenhower's forward headquarters in Reims in northern France, which was to coordinate the interrogation of the prisoners.

On 30 April 1945, the Americans took over the keys of the Palace Hotel in Bad Mondorf and began to convert it into Camp Ashcan. In the process, they had to reckon with liberation attempts by fanatical Nazis as well as acts of revenge by resistance commandos or the local population. The Palace was an older hotel that had fallen into disrepair under the German occupation. With the help of German prisoners of war and local craftsmen, it was transformed into a prison with a high security fence and watchtowers. The windows were barred and covered with Plexiglas. The hotel furniture in the rooms was replaced by basic military equipment with a cot, chair and two bedsheets. Nevertheless, the hotel still looked like a luxury hostel from the outside. The concern of the inspectors sent by the US headquarters that the accusation could be made that high-ranking German prisoners of war enjoyed the luxury of a spa hotel was not unfounded, as it was to turn out.

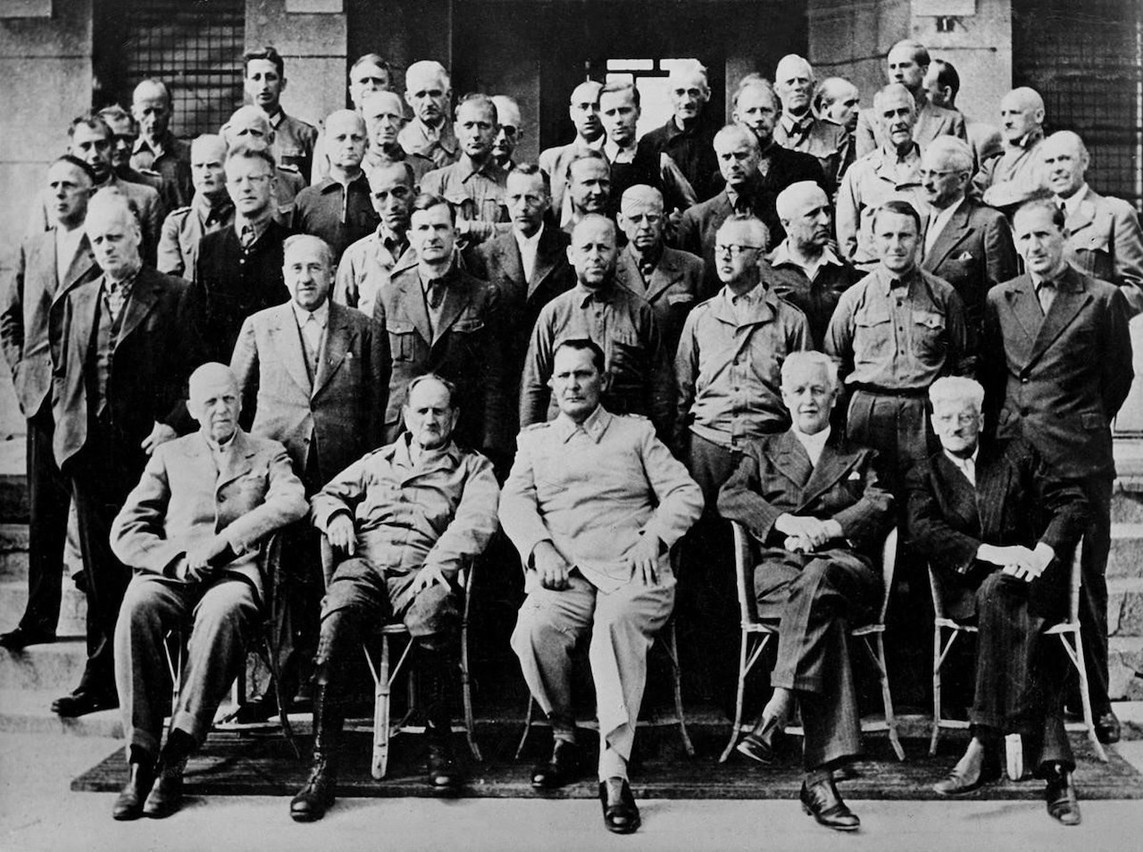

The inmates

In mid-May 1945, the camp was put into operation and the prisoners were transferred from Spa in Belgium to Bad Mondorf. By August, about fifty prisoners were interned at any one time. On 20 May, Göring, who had surrendered to the 36th US Infantry Division in Austria on 9 May with his wife, daughter and some staff, was brought to Bad Mondorf. If his capture had already caused a great stir, much to Eisenhower's annoyance, he immediately became the “star prisoner” in Bad Mondorf as well. Drug-addicted and heavily overweight, Göring brought with him in his seven suitcases not only large quantities of paradozin (a morphine preparation), but also a large number of valuables and uniforms, which were immediately confiscated. Under the supervision of first a (imprisoned) German and later an American military doctor, Göring was subjected to a drug deprivation cure. Thanks to the prison diet, which corresponded to the 1,600 calories prescribed by the Geneva Convention for prisoners of war, he soon lost weight. When he was transferred to Nuremberg in August 1945, he was in the best physical condition he had been in for years.

Daily prison life

The prisoners took their meals together in the dining room of the former hotel and could spend their free time, when there was no interrogation, in the reading room or playing games. Many sat on the terrace or in the garden on sunny days. The accommodation was much better than in the normal POW camps, which particularly offended the Soviets. In a report handed over to Stalin on 30 June 1945, Commissar of State Security Ivan Serov wrote: “It turned out that the prisoners were staying in (...), one of the best health resorts. They lived in an excellently equipped four-storey building. The windows had only weak bars. In this building, each prisoner has his own room with a good bed and other amenities of everyday life. The isolation of one from the other is only limited, because in the course of the day they have several opportunities to meet each other for meals, but also during a game of chess or other games. None of the interrogated persons gives the impression of a prisoner who is ready to take responsibility for his crimes. They all look good and are tanned like spa guests. All dressed in full uniform, with degree badges and the swastika.”

Nevertheless, quite a few of the prisoners complained about the accommodation, the food or generally about their “status” and wrote letters to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, British prime minister Winston Churchill and US president Harry S. Truman. To no avail, because American, British and French media had already published criticism that the internees were being treated unduly courteously. This earned Eisenhower fierce criticism. The prison authorities attached great importance to the health of the inmates and took measures to prevent them from evading their responsibility in court by committing suicide. No shoelaces or belts could be worn, no knives or forks for eating, and even glasses could only be worn in the reading room under supervision.

The inmates fell into three groups: The first consisted of the high-ranking generals such as Wilhelm Keitel, Albert Kesselring or Alfred Jodl as well as the admirals Dönitz and Gerhard Wagner. The first three were particularly close to each other, while Dönitz often acted as spokesman for the group and also claimed the first seat at the dining table for himself.

The second group consisted of politicians and civil servants. What this group had in common was that its members had no understanding of being interned at all. They were among the most difficult inmates and the busiest writers of complaints. From this group, only the former Vice-Chancellor and diplomat Franz von Papen, who had married into the Boch-Galhau Luxembourg-Saarland-Lorraine business family, was tried and acquitted in Nuremberg.

The third group consisted of the high-ranking Nazis, some of whom had belonged to Hitler's entourage as “old fighters” from the 1920s onwards. This group also came together because the members of the other two groups avoided them. Göring would have fit into all three groups because of the many offices he had held, but who was not welcome in any of them. But that did not stop him from acting as spokesman for the inmates at every available opportunity.

The interrogations

The Allies believed they did not have a sufficient understanding of the workings of the Nazi state and Nazi rule. Therefore, it fell to the 6824 Detailed Interrogation Centre (DIC) to learn more about the workings of the Third Reich from the inmates at Bad Mondorf. Five military intelligence officers, including Luxembourg native and later US ambassador to the grand duchy John Dolibois, conducted their interrogations along the lines of questionnaires transmitted from Allied headquarters.

In addition, the US War Department sent a commission of historians to interrogate the prisoners. They dealt with the structure and tasks of ministries and organisations as well as the financing of the Nazi state and the war. Other interrogations related to the use of foreign workers and the theft of art and cultural assets. A third set of questions targeted the concentration camps and the murder of the Jews.

Finally, a fourth area of interest for the Americans related to the nuclear programme. Dönitz confirmed that the "Reich" had also pursued such a programme in 1943, but that it had failed for lack of resources. He insisted to his American questioner that everything must be done to prevent the Russians from gaining access to this destructive bomb.

The interrogations were more like questioning, as the interrogating officers rarely followed up even on inconsistencies and obvious lies. There were also hardly any questions - in view of the upcoming trials - aimed at the inmates’ personal guilt and involvement in the crimes of the Nazi regime. The prosecutors of the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg (IMT) therefore dismissed the interrogation protocols from Bad Mondorf as useless: Ashcan had failed due to “indecision, lack of imagination and training” of the interrogators. Moreover, the Allies had discovered large quantities of files in caves and mines during the summer, so the IMT decided to base the indictments on these documents signed by the accused rather than on witness statements as originally planned.

At the end of the war, the Allies had not yet agreed on what to do with the Germans who were considered major war criminals. The victors were hardly prepared for a legal reappraisal of the war and Nazi rule. It took Roosevelt and Churchill, who both initially envisaged a simple execution of the main war criminals just like Stalin, to agree on a trial. It was not until the London Four-Power Conference, which lasted from 26 June to 8 August 1945, that agreement was reached on the charges and the London Charter signed there established the IMT.

Nuremberg was chosen for the trials not only because it had an intact courtroom and prison, but as the city of the Reich Party Congress, where the anti-Semitic racial laws (Nuremberg Laws) had been passed in 1935, it was of great importance to the Nazis.

The trial began on 20 November 1945 and was to last until 1 October 1946. Twelve of the accused, among them Göring, were sentenced to death by hanging. Göring took his own life with a cyanide capsule the night before the execution. Seven defendants received prison sentences, three were acquitted, and two cases were dropped.

Silent to Nuremberg

On 10 August 1945, Lieutenant Dolibois escorted the prisoners in a convoy of six ambulances from Bad Mondorf to the court in Nuremberg. In his truck were Dönitz and Kesselring, among others. “After our convoy had crossed the Moselle into Germany, the nervous chatter of my passengers suddenly fell silent in Trier,” writes Dolibois. “Through the back window of the car they could see what had become of their glorious Third Reich. A large part of the city lay in ruins. They were shocked, speechless, one sobbed unrestrainedly. The rest of the journey was in silence.”

Camp Ashcan was closed on 12 August 1945. The Palace Hotel later resumed operations and was also used as a casino. In 1988, it was demolished. Luxembourg thus lost a historical monument, but also removed a potential place of pilgrimage for neo-Nazis.

Heinrich Kreft holds the Chair of Diplomacy and heads the Centre for Diplomacy at Andrassy University in Budapest. Previously, he was Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Germany in Luxembourg from 2016-2020.