The increase in customs tariffs in the United States, which was sudden and much more severe than anticipated, is unique in economic history. The average US tariff rate, multiplied by a factor of around 10, is now at its highest level for more than a century. Close to 150%, the rate applying to Chinese imports constitutes a de facto embargo, untenable in the long term, on the second largest economic power.

This return to a protectionist policy across the Atlantic brings to an end a very long period marked by increasing globalisation of trade, favourable to world economic dynamics.

Complex economic ambitions to implement

The objectives pursued by the US administration are clearly announced: a “re-industrialisation” of the United States through the repatriation of activities to US soil, a correction of US trade deficits through an increase in exports and a reduction in imports, and the generation of revenue allowing for tax relief.

However, these objectives can only be achieved--at best--in the long term, measured in years. Repatriating production lines to the United States requires substantial investment, which cannot be achieved in the short term. The return on these investments could also prove insufficient. Production costs will inevitably be higher, and the final prices of goods will rise sharply, with the risk of squeezing consumer demand and company margins. The long-term benefits of this protectionist policy for the US economy are highly uncertain. In the short term, however, the initial consequences are already clearly visible and, unsurprisingly, clearly negative.

First impact on confidence indicators

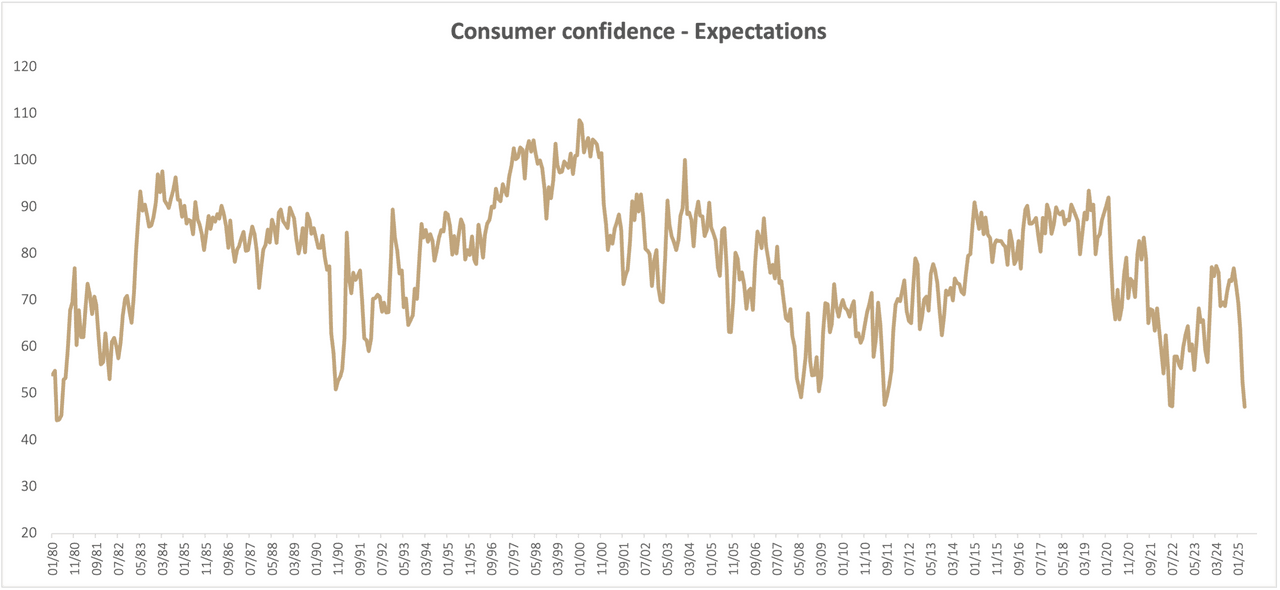

Confidence indicators are falling sharply, both at business level and among US consumers, the driving force behind the economy. What’s more, consumers are expecting prices to rise sharply over the next 12 months, to a level not seen since the early 1980s.

It is important to remember that around 40% of spending in the United States is carried out by the 20% of consumers with the highest incomes. With the recent market correction (the S&P 500 has lost almost 20% in local currency terms from its peak in mid-February), this segment of affluent consumers is now being penalised by negative wealth effects. In addition, less well-off households have used up the excess savings generated during the covid period.

Evolution of consumer confidence expectations. Source: University of Michigan, Banque de Luxembourg

Consumer confidence, median 12-month inflation expectations. Source: University of Michigan, Banque de Luxembourg

More surprising and worrying than the fall in the equity markets, long-term rates rose sharply at the start of April. This is a strong signal for the US administration, which is facing a serious deterioration in its public finances, and a wake-up call from the bond market. The dollar is also weakening significantly, with president Trump’s sharp criticism of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy and his desire to replace its chairman Jerome Powell raising fears of a loss of independence for the US central bank.

Under pressure from the markets, Donald Trump was therefore forced to react, announcing a suspension of reciprocal tariffs--with the notable exception of China--for a short period of 90 days. This initial about-face was intended to give bilateral negotiations a little more time and--above all--to calm the markets. It was followed by others, including in particular the exemption from reciprocal taxes on electronic goods such as computers and mobile phones, reducing tariffs on these goods from China to 20%.

A Chinese riposte little appreciated

President Trump little appreciated the Chinese riposte. Chinese authorities also announced several successive increases in customs duties on American products, bringing the rate to the prohibitive level of 125%.

The US administration seems to be underestimating China’s ability to resist. Chinese imports into the United States are worth around $450bn, or around 13% of total imports and 1.5% of US GDP. However, a large proportion of these imports are difficult to substitute in the short term, particularly in the electronics and technology sectors. China, on the other hand, can more easily continue to reduce its dependence on US imports--which accounted for 13.4% of the country’s total imports in 2024, compared with over 20% in 2016--particularly when it comes to agricultural products or energy.

Non-tariff retaliatory measures have also been adopted by China, including the suspension of exports of several categories of rare earths, essential components for many US industries (defence, technology, etc.). In addition, the Chinese consumer’s rejection of major American brands is likely to have a negative impact on the sales of many multinationals on the other side of the Atlantic. Finally, China also has the option of relaxing its fiscal policy further in order to encourage domestic consumption.

In conclusion, the trade war launched by the new Trump administration is likely to slow global growth significantly and generate a temporary surge in inflation. A recession scenario cannot be ruled out on the other side of the Atlantic. The longer it takes to conclude bilateral agreements with key partners, particularly China, the greater the economic damage will be. Whilst the United States continues to enjoy significant competitive advantages in the technology, energy and even military sectors, this sudden return to a protectionist policy is likely to call into question the country’s credibility as a reliable trading partner.

Damien Petit is head of private banking investments at Banque de Luxembourg.

This article was originally published in .