Located in Switzerland’s Vallée de Joux--a valley where other great names in the watchmaking industry such as Audemars Piguet, Blancpain and Jaeger-Lecoultre coexist--the Breguet manufactory houses over 25,000 m2, where more than six hundred employees work on the company’s timepieces every day. The manufacturer rarely opens its doors to visitors. And when it does, it is mainly for customers, who can meet the people behind each component of the timepiece. Paperjam shares this experience with you.

First stop: the store

This is not the most glamorous part of the manufactory, but it is a strategic and indispensable location. All the materials needed to make a watch, like the steel and other metals, are stored here.

Steel of various grades, gold, brass... All the materials needed to build a watch can be found here. Photo: Marc Fassone/Maison Moderne

Second stage: stamping

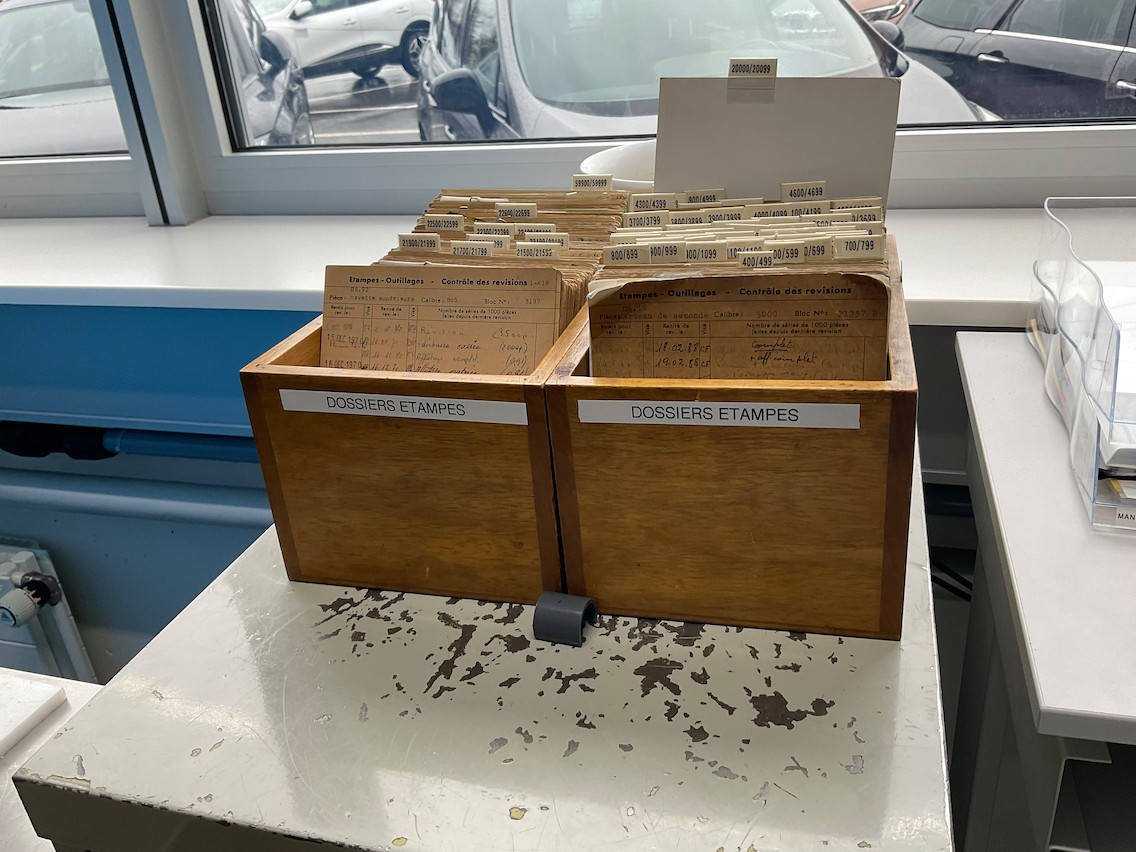

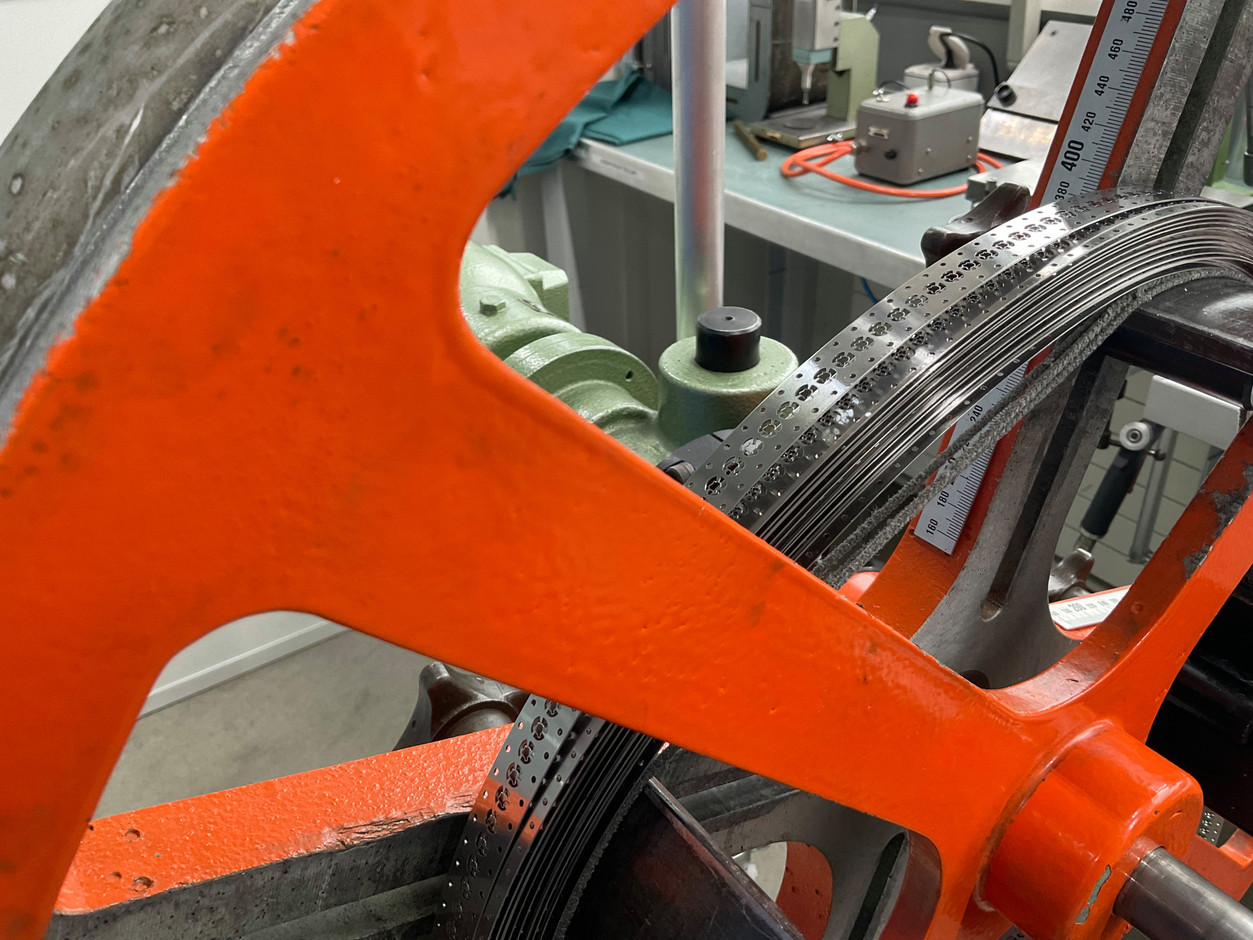

Each piece is cut on site in this room: the stamping room. Since the 16th century, jewellery, coins and mechanical parts have been shaped, formed and/or cut using stamping presses. This high-precision tool revolutionised the manufacture of mechanical watches. It can be used to form, drill, grind and cut out most of the components of a watch, as well as for most metals.

This step requires the manufacture of cutting tools specific to each design: the stamp. Breguet has several hundred carefully maintained stamps, which are cleaned and sharpened between uses.

Nothing is lost, nothing is created. The offcuts following stamping are recovered and will be recycled for return to the shop.

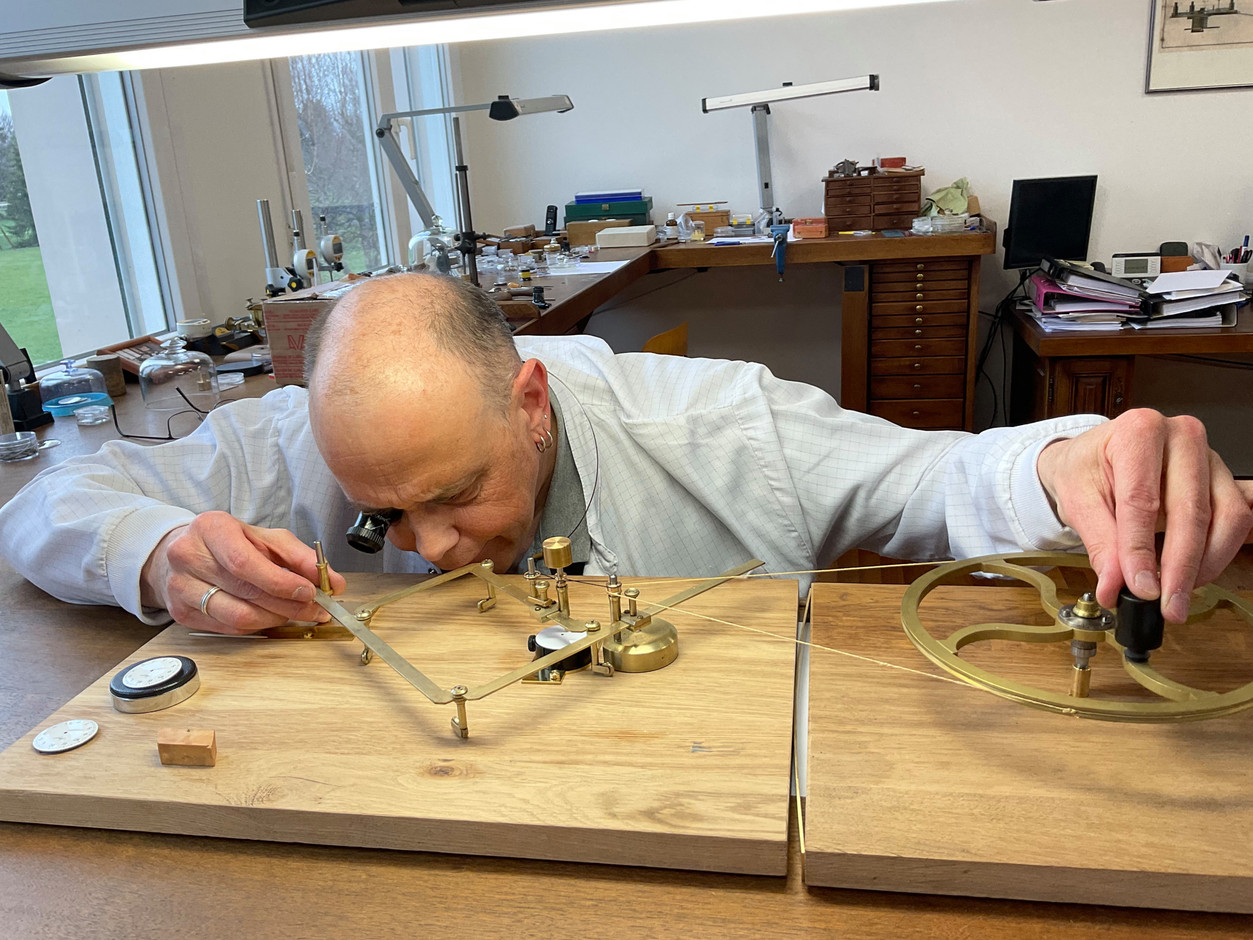

Third stage: guilloché

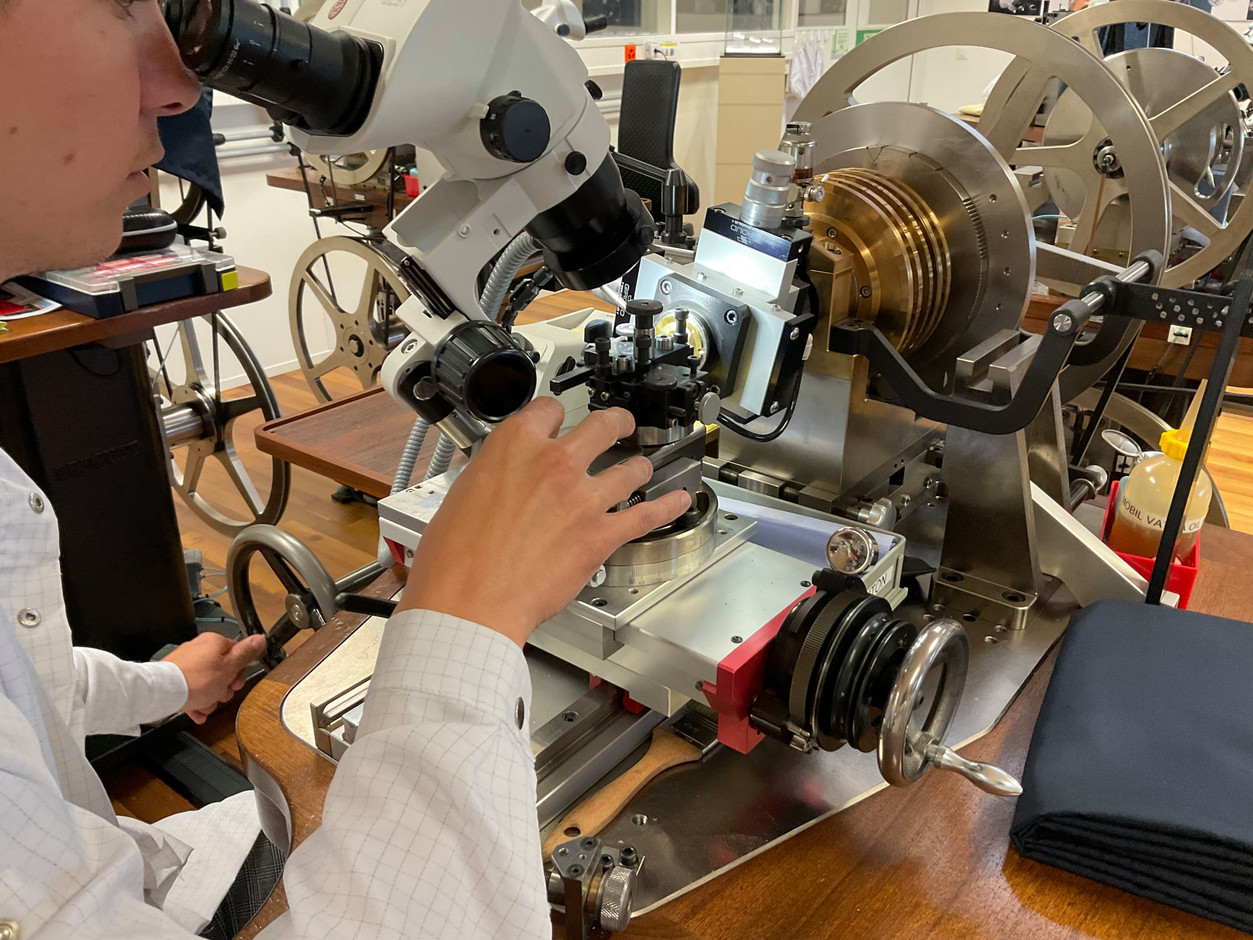

Guilloché is an engraving technique that makes it possible to engrave very fine grooves and patterns on a watch dial by removing material. At Breguet, guilloché is a signature process, and the manufacturer has the largest guilloché workshop in the world. Machines--which no one knows how to make anymore--are used to remove material with a chisel. The left hand operates a crank that turns the workpiece and positions the chisel precisely according to the chosen motif; the right hand applies pressure to the chisel to complete the cut. All materials can be guillochéd more or less easily--and therefore quickly. Depending on the size of the dial, its material and the design, the operation can take several days.

There are two categories of guilloché machine, depending on the type of work to be carried out: the straight-line machine, which is used to make a linear decoration; and the guilloché lathe, which is used to make circular decorations where the grooves criss-cross and intertwine.

Machines are rare, are the specialists who operate them. There is no training for guilloché-makers. Workers are trained on the job, which can take several months.

Gillo engraving responds to specific problems. Originally--two centuries ago--it was used to hide imperfections on dials. It also cut out the sun’s rays to improve visibility, as glasses of the time were less effective. Today, they allow the various sub-dials to be better highlighted.

Fourth step: bevelling

Bevelling is a manual or mechanical operation that involves breaking the angle forming the edge joining two surfaces for aesthetic or technical purposes. Depending on the aesthetics required, the profile and dimensions of the component, and any technical constraints, the angle of the corner can be adjusted. Bevelling can be for decorative or technical purposes.

In the case shown, a platinum is bevelled. The plate is the base plate supporting all the components of a watch’s mechanical movement. For all the components to work harmoniously together, all the angles must be precise. Angleurs use files and wood-based tools made from boxwood or juniper that have been harvested from the forest and cut by hand. At Breguet, bevelling is done by hand. Here too, there is no training for bevellers. People are trained on the spot. The desired profile? A person who is calm and punctual.

Fifth stage: engraving

At Breguet, engraving is an art--and a trademark. Dials, cases and oscillating weights are often engraved. From the moment they enter the factory, engravers build their own tools. It’s said that each of these craftsmen can recognise a watch he has worked on.

Trained in-house for the most part--and with the benefit of several years of experience--the artisan engravers have acquired the ability to respect an artistic grammar specific to the manufactory, whilst retaining their own particular aesthetic vocabulary, the essential richness of all craftsmanship. Whilst intaglio engraving (scroll motifs) accounts for most of the work--particularly on the bridges, mainplate and middle case--other techniques such as relief engraving and intaglio engraving are also part of Breguet’s expertise. An extremely rare detail in the industry--also practiced at Breguet--consists of hand-engraving the letters and numbers appearing on the backs of watches.

Sixth stage: restoration

This is not after-sales service. Restoration concerns models that are over 200 years old for which the plans and parts are no longer necessarily available. So these are rebuilt one by one, by hand--just like the tools used to produce them.

The founder of the manufacturer, Abraham-Louis Breguet, wanted his timepieces to be repairable by any watchmaker. It’s a desire that influences the way components are placed, which helps restorers.

This article was originally published in .