Today, there are more than 13bn connected intelligent objects. This number is rising steadily and is expected to reach 25.4bn by 2030. The significant growth of this market is obviously linked to its financial potential, estimated at $1trn by 2024.

These intelligently connected objects offer a myriad of advantages in our daily lives, revolutionising the way we interact with our domestic environment: it is now possible to control lighting and heating remotely, and even to prepare our coffee before getting up.

The IoT in a nutshell. Source: Dreamstime.com

In addition to connected homes, many other sectors, such as transport and logistics, are benefiting from this technology by providing personalised information. Goods and assets can be tracked and monitored throughout the supply chain via sensors embedded in products and containers.

But can intelligent connected objects become intimate enemies? When you talk about the IoT, you talk about connectivity and the processing of sensitive data, particularly personal data.

Intelligent connected objects are computer systems. Like all systems, they have security flaws, which are usually corrected by updates, but they still represent a playground for cybercriminals. They invite themselves in without permission to take remote control of our smart locks, security systems and surveillance cameras. And they don’t lack imagination!

Some cybercriminals have managed to hack into a casino in the US, for example, using thermal sensors in an aquarium as an entry point. Baby monitors are not immune to their malicious talents. Cybercriminals are able to gain access to the camera, causing concern among many parents. In France, they have even managed to hack into petrol stations, once again using smart connected objects as their point of entry, helping themselves to free petrol at the pump before reselling it at low prices to private individuals.

The “new” thing about compromising these objects is that you no longer need to be an IT expert to do it. Many freely accessed video tutorials are available on well-known social networks, explaining how to easily hack into smart connected objects.

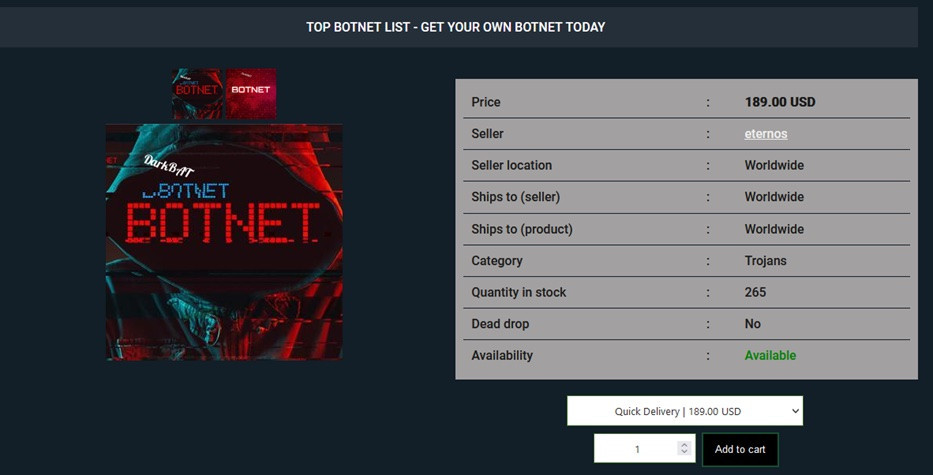

If these videos aren’t enough, criminal organisations sell access (or backdoors) to smart connected objects on the darknet for a few dollars. Another notable example is botnets, networks of smart objects compromised remotely and controlled by cybercriminals.

A botnet offer for non-experts in cybercrime. It’s one of the current problems. Source: Benoît Poletti

These infected objects, such as security cameras, routers or smart thermostats, are used to launch massive denial of service (DDoS) attacks or to carry out other harmful activities, without their owners being aware of it. One well-known DDoS attack was in 2016, when the Mirai botnet was used to disrupt services at Twitter, Netflix, Reddit and many others. This botnet is said to have been behind more than 20,000 attacks, and in its heyday controlled more than 600,000 smart connected objects without the knowledge of their rightful owners.

And if controlling access to a single connected smart object is no longer enough, cybercriminals can rent out full access to all infected objects linked to botnets. This means that even novices can afford a cyber attack! So it’s all a question of money. The accessibility of these systems unfortunately facilitates the spread of cybercrime.

Although attractive, the connected intelligent object has an ambiguous relationship with its owner. In the near future, the IoT will take connectivity and functionality even further, and promises to spice up our daily lives.

Science fiction stories such as “Cyberpunk 2077” or George Orwell’s classic novel “1984” have already shown us a disturbing glimpse of the possibilities that cybercriminals can exploit through the IoT. These works of fiction have plunged us into dystopian worlds in which there is ubiquitous surveillance through connected objects, where malicious people hack into transport systems or take control of urban infrastructures.

The lack of security in the IoT creates a breeding ground for abuse of power, invasion of privacy and loss of individual control.

That’s why experts and regulators are implementing systems and trust models in which IoT cybersecurity is an absolute priority.

Is this the solution? We’ll see...

*Benoît Poletti is director general of the public agency , considered to be a centre of expertise in the fields of cybersecurity and digitisation. The agency manages critical national and international IT infrastructure, as well as developing solutions used in identity management and cryptography. Poletti represents Luxembourg in European and international bodies such as UN agencies, and also works internationally on cybersecurity and digital governance issues in emerging countries.

This story was first published in French on . It has been translated and edited for Delano.