A ballet of fury and mechanics. Connected machines hovering in the air, pallets gliding along the ground with no one to pull them. Metal staircases, lots of them. Steps, lots of steps. And more stairs. Climbing, branching off, plummeting. Vertiginous. And labyrinthine.

Welcome to the Recy warehouse, a few minutes’ drive from Châlons-en-Champagne--in the Marne département, about 200km southwest of Luxembourg City--the nerve centre of Scapest, Leclerc’s purchasing and logistics centre for a large part of eastern France. In the coming months it will serve as the rear base for the 27 Cora, Match and Smatch shops acquired from the Delhaize group by France’s largest supermarket chain. Scapest played a major role in the transaction.

Here is somewhere else. This is nowhere. An anonymous industrial estate without a soul or much greenery, topped by a grey sky on a Thursday afternoon when the radio news flashes the chronicle of the ongoing agricultural crisis. In France, central purchasing bodies such as this one have been targeted by the demonstrators, who see them as symbols of the influence of the big chains on their difficulties in making a living from the fruits of their labour. “But the demands mainly concern the state, and very little the retailers”, said Scapest chairman Serge Febvre, who has also owned the Leclerc hypermarket in Thionville since 1994.

In cooperative mode

This is in fact his home. A gigantic building constructed in the summer of 2013 and brought into service less than two years later, in autumn 2015. What makes it special is that almost everything is automated, with human intervention only required for around 3% of products received. One of the few warehouses to operate in this way in Europe, it is also the flagship of Scapest, one of the 16 regional centres that supply Leclerc stores in France.

Serge Febvre (right), chairman of Scapest, and Olivier Fache, its director, at the heart of the warehouse, where 95% of products require no human intervention. Photo: Maison Moderne

To understand how it works, you first need to understand the Leclerc model, which is very different from that of integrated groups such as Carrefour or Auchan, with a chairman and a pool of shareholders and decision-makers under whose authority the shop managers are placed. At Leclerc, the decision-makers are the members. In other words, independent retailers who own their own stores.

The cooperative network of 1,386 sales outlets in France (nearly half of them hypermarkets), representing 624 members, 132,000 employees, 23.2% market share and sales of €43.9 billion (excluding fuel) in 2022, is headed by two entities. First, there is the ACDLEC (Association des centres distributeurs E. Leclerc), an association under the law of 1901 chaired by the group’s big boss, Michel-Édouard Leclerc. That is “where all the major strategic directions are set”, said Serge Febvre, chairman of Scapest, who has a seat on the ACDLEC committee with his 15 other counterparts. Second, there is Galec (for Groupement d’achats E. Leclerc), which is responsible for all commercial matters. “We’re all about operations.”

The power is in computing. A parcel responds to five algorithms.

In practice, it’s a circular system. Let’s take the example of the 180 shops (including 47 hypermarkets and supermarkets) in Scapest's catchment area, which extends as far as the Paris region and is preparing to conquer Luxembourg in the coming months. Each shop expresses its needs to Scapest. Scapest then consolidates the orders, liaises with the suppliers, takes delivery of the goods, prepares the parcels and delivers them. This concerns around two-thirds of the items on the shelves.

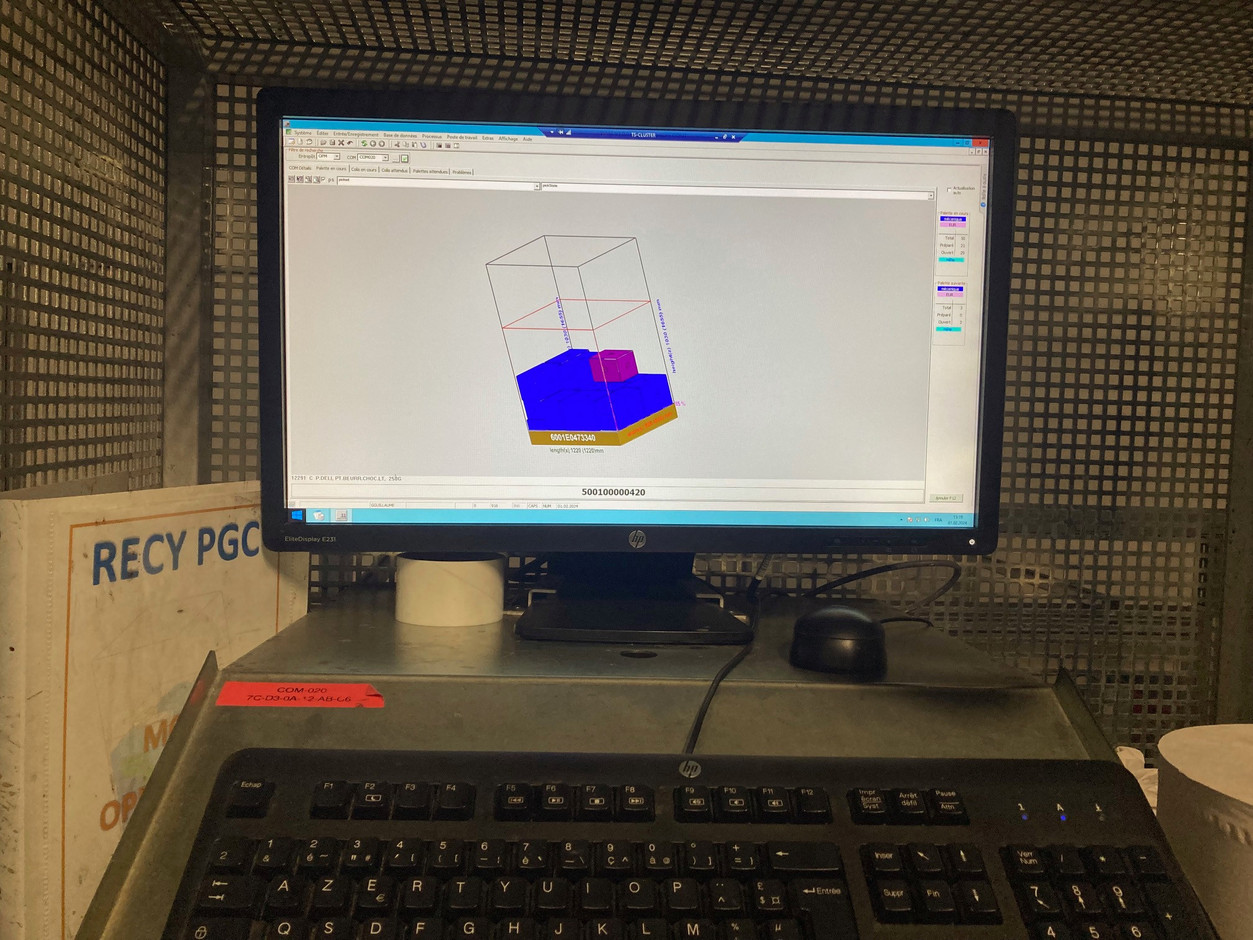

Pallets and Tetris

The Recy site is all the more impressive because it handles between 4,000 and 4,500 pallets a day, each weighing 500kg. Between 100 and 150 lorries leave every day, bound for Leclerc shops. In the meantime, the main challenge has been to put together what Scapest director Olivier Fache compares to “a Tetris”, i.e. a package that is duly tied up and arranged to meet the needs of the physical organisation of each shop. The “computer power” of this warehouse, having required the work of half a thousand workers, “concentrates on putting together these Tetris. A parcel responds to five algorithms”, said Fache.

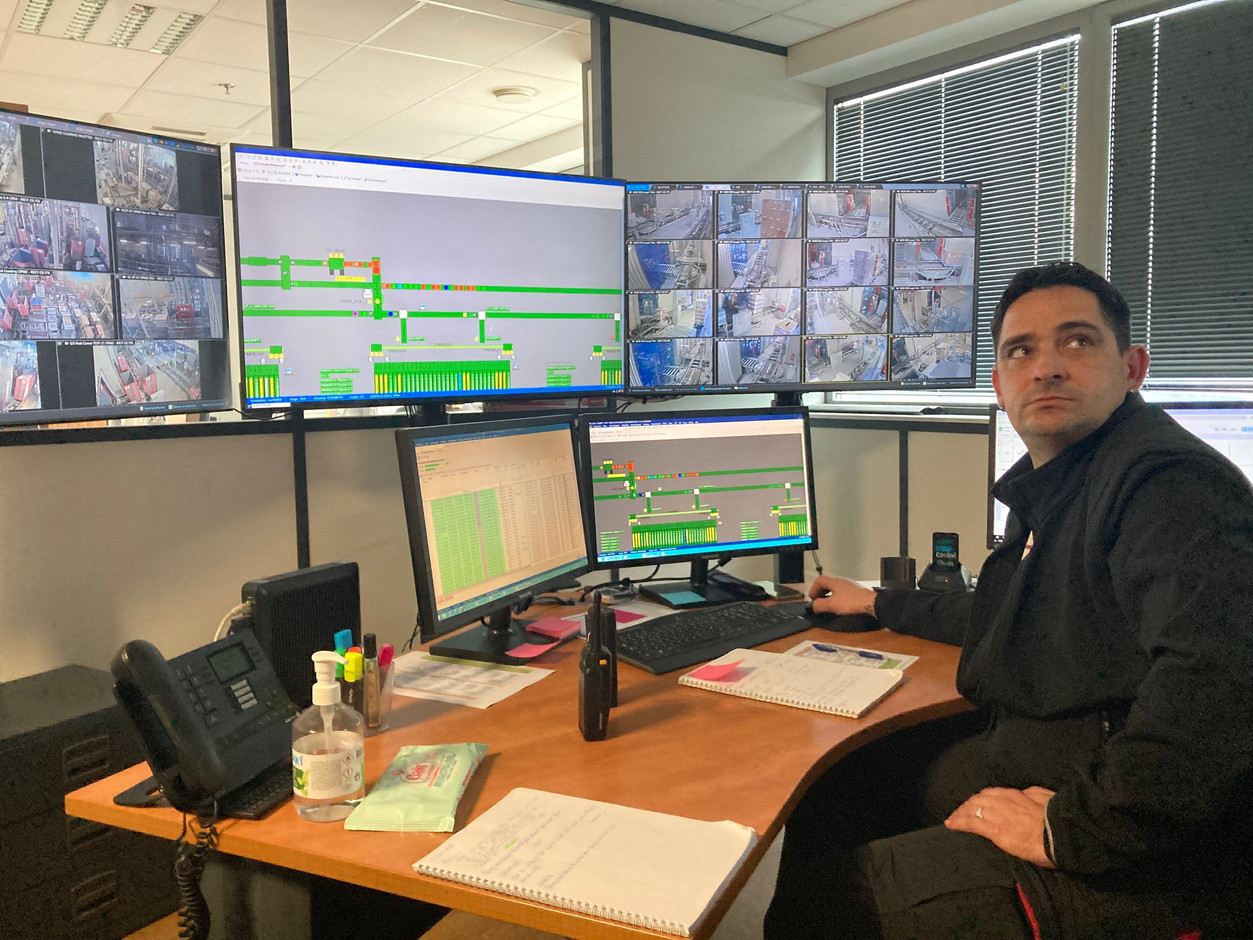

Human intervention is limited to unloading and then loading the vehicles. For the rest, the products all follow the same circuit, from the point of entry to the exit, passing in turn between the ‘claws’ of stacker cranes capable of moving them or picking them up from a height of around twenty metres, nine unstacking stations, a suction hood responsible for undoing the layers of each parcel one by one, a sequencer assigning them to their destination zone and a filming machine made up of four devices, capable of handling 1,000 Tetrises every day. A computer control room is located on the upper floors. With their eyes riveted to three giant screens displaying up to thirty views simultaneously, a control officer can intervene at any time in the event of a malfunction.

We’re not going to bring in local goods from Luxembourg and then send them back.

This is where orders will soon be received and parcels prepared for the two Cora hypermarkets and 25 Match and Smatch shops that have been part of Leclerc since last summer. The roll-out schedule is currently being finalised, but has not yet been disclosed. Everything should be completed by the end of the first half of 2024. The first hurdle will be rolling out Leclerc’s own IT system.

As Leclerc has stated from the outset, its intention is to draw on the local know-how of the teams already in place at Cora, Match and Smatch (over a thousand jobs have been retained) and on part of the local organisation. In terms of logistics, this means that apart from a few adjustments, Scapest, which already serves 403,000 square metres of sales area on the French side, will hardly need to expand its premises. As far as Luxembourg goods are concerned, for example, the business will be run from Arthur Welter’s warehouses in Leudelange. “We’re not going to bring in local goods from Luxembourg and then ship them out again,” said Scapest chairman Febvre.

The revolution is underway, in any case, with the importation into the grand duchy of a cooperative model that will soon see members in Luxembourg, but also in Belgium, France and Germany, holding in their name one or more of the 27 sales outlets sold by Delhaize. It’s an opportunity for Scapest to grow even bigger. With sales of €3.9bn in 2023, an increase of 10%, the structure founded in 1975 to supply six shops at the time, is proud to account for 8.4% of the national sales of the Leclerc giant.

Originally published in French by and translated for Delano