After seven years, the novel is out!

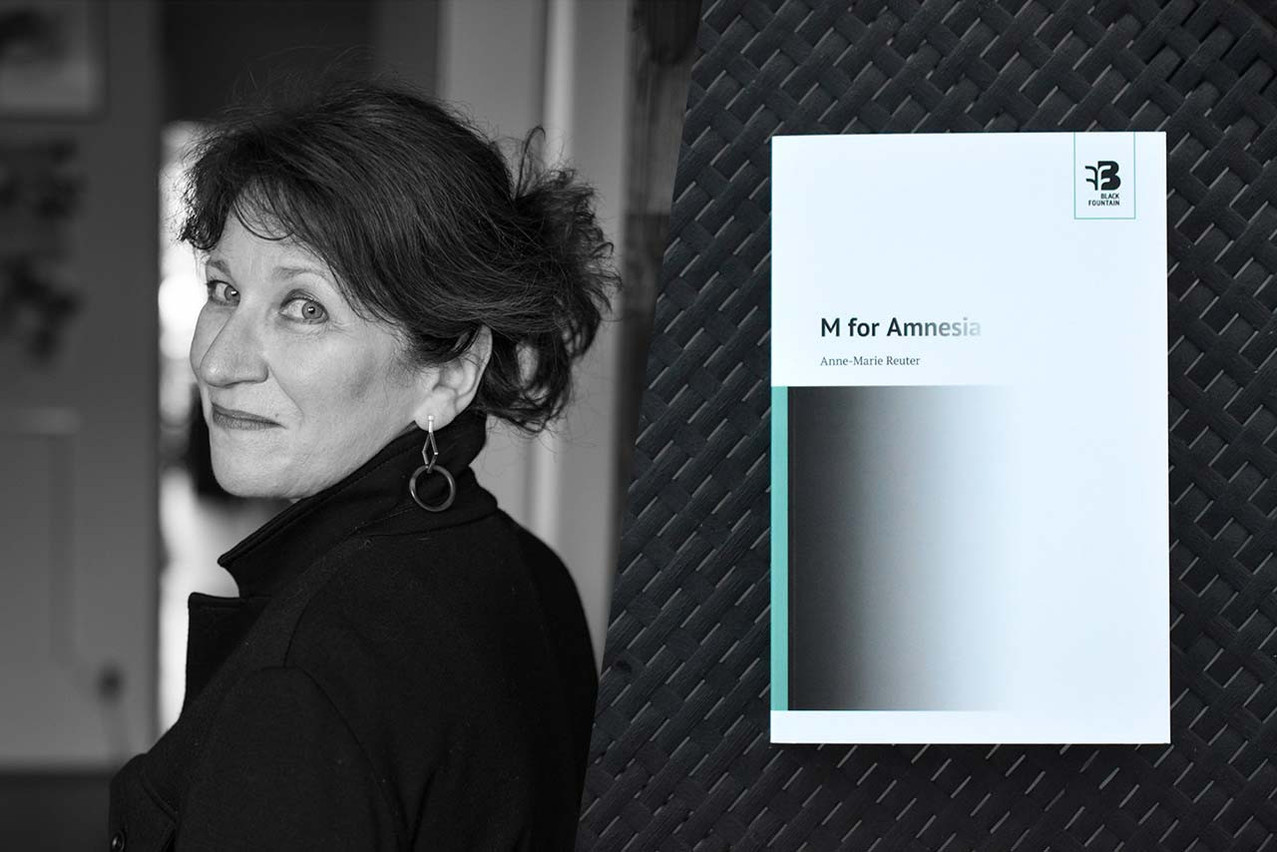

Anne-Marie Reuter’s M for Amnesia was launched on 11 July 2024, following up her earlier works: stories (2024) and (2021), published as their own illustrated volumes; and short story collection On the Edge (2017).

Reuter has a PhD in English and comparative literature and, in 2017, cofounded Black Fountain Press, the first all-English publishing house in Luxembourg. M for Amnesia is her first novel.

The news of my father’s death reached me the day after my performance on Dolby Hill. The festival had been a wild event, one of those we rarely pulled off as we were all camping in different places and reluctant to travel. Styx had breezed in with his antenna fine-tuned and calibrated, ready to electrify the audience…

In conversation

Jeffrey Palms: From the opening words of M for Amnesia, time is a little dislocated, with the narration practically starting in the past perfect tense: Melissa says that she received news of her father’s death one day after her musical performance on Dolby Hill, whereafter we plunge into that festival in a whole passage that hangs in an unmoored temporal space existing longer ago than this novel-opening news, itself not necessarily tied to the moment of that death. You’ve said that memory is paramount in this novel. If writing the book constitutes research into memory--and possibly time beyond that--then what discoveries have you made?

Anne-Marie Reuter: It was clear to me from the outset that writing about memory would require a non-linear approach as we don’t necessarily remember the entirety of a story, its details or the exact chronology. I was initially tempted to avoid a proper plot altogether and let the story unfold through patches of memory. I gave up after a while: the result was unreadable! What I discovered when I went back to plotting was that my research into memory was, in fact, also a research into time. As Faulkner says, “The past is not dead. It is not even past.” Past and present merge the moment we remember--Proust’s madeleine will always remind us of this. If you apply this idea to people who suffer from traumatic events in their past, the experience becomes a very different one. And if you include the future, the future from the past or present perspective, or the present and the past from the future perspective, with flashbacks and foreshadowing, then time becomes a volatile concept. Add to this the realisation that the past can change with information gained in the present and that a new perspective can alter one’s views of the past, and we’re in a loop of various time levels, all entwined and spiralling madly.

Wow. I appreciate the novel as a medium for this, considering that novels are something (typically) read silently and stored--never in their entirety, of course--in the brain of the reader, meaning that the fictive pasts, presents and futures of the book will be further fragmented by our own faulty memories of what we’ve read. However, I fear that I’m being tempted into concept-gazing, here, so let me ask you: your exploration of memory includes the future (for the interesting reasons you describe), so what kind of future does M for Amnesia portray and why?

I’d listened to Jean’s story. That was her story. When I told it to Styx on the train, it became my story, and it was different in tone.

It’s a future that is shaped by technology. Due to climate change and the ensuing problems of migration and wars, humans now use high-tech devices to become more competitive and have better chances of survival. Health and self-improvement are key matters in this world. Cosmetic surgery is a banal routine, the insertion of implants or sensors everyday business--for those able to afford those procedures. While life in the countryside is still relatively normal, even though certain kinds of food are gone, life in the city is more threatening with the divide amongst the enhanced citizens and the unenhanced “creatures,” jobless, homeless and victims of the government’s fumigation methods.

I see plenty here that is familiar from our present day: a technology-first approach to solving problems, and the class and social wars that ensue when--surprise!--not everybody in the world can afford those technologies. But does the novel celebrate technology as well? This, I think, is one of the built-in concessions of even cautionary science fiction, that merely by focusing on implants, gadgets, etc. the world becomes “cool.” Nothing is more frustrating than readers who take this “coolness” as a binary on which to understand the text. (First to mind is of course Elon Musk and his claim to have been inspired by the high-tech utopias of Iain M. Banks, characteristically missing the anti-capitalist point of those utopias.) M for Amnesia is clearly punching high in its literary weight class, so I’m absolutely not accusing it of being by distracted by anybody’s idea of what’s “cool,” but I do think that this is something for science fiction writers to worry about since, as I’m suggesting, merely granting attention to futuristic tech is a form of celebration of it. So would you talk us through your tech politics?

The novel presents two characters who bear the consequences of technology. Melissa, the daughter of the scientist who has played a major part in shaping this society of optimisation, has turned her back on civilisation and joined a commune after acrimonious fights with her father, whose research she condemns vehemently. Millie, the amnesiac of the novel, has lost her memories because of technology. The suffering these two characters undergo can be seen as a massive criticism. And yet, Melissa’s commune gathers the dropouts of civilisation, the “digital savages,” who continue to benefit from their enhancements so much so that they end up making everyone’s life richer, and even serving the planet. Millie herself cannot help defending science. She is marked by an inherent trust in progress. “It’s always easy to criticise science in the aftermath” is what she says. I think what links the two women is that they reject a simplified criticism of science and technology. Do they want to be “cool”? I’m not sure. They are certainly worried, excited and intrigued. After all, you can’t unmake a discovery, you can’t ignore new possibilities or go back in time and pretend it hasn’t happened. Maybe sometimes it would be safer to stick your head in the ground, for ethical reasons or others…

All right, I see a distinction between the opportunistic use of existing technology for the benefit of people (on one hand) versus the tragic fallout caused by enterprising researchers (on the other). A touch of solarpunk in there, maybe? It seems to me that this is becoming a defining issue of our era: the ethics of technology-users and whether technology can--someday, somehow--be seized back by the “small folk” and deployed for more good than bad. These anxieties in your book, and how they manifest within complex characters, promise to be fascinating.

But turning now to your process: I understand that it took you seven years to complete this novel, which is your first. Will the next one go faster? In terms of craft, any lessons learned?

I hope that next novel will go faster, although I don’t actually mind spending time thinking and planning and mulling matters over. Without my teaching job and the Black Fountain publishing work, I think I could have finished my first novel in five years, instead of seven, but I don’t think I would have finished it much faster than that. Lessons learned? Absolutely! Many! “Burn through the first draft” is Joyce Carol Oates’s recommendation, and I couldn’t agree more. I will not start my next novel unless I know I have a suitably long stretch of time straightaway at the beginning of the project. As far as craft is concerned, I have had to switch from the faster, sparser, terser style of short stories and flash fiction, to a smoother, softer descriptive style. Rhythm has become more important, changes between plot and scene, between reflective passages and action. And the greatest challenge was to try and keep up the interest or suspense over so many pages. That is the greatest difference: you juggle around with so many more words and pages.

Transorbital lobotomy. / Pick-like instrument. / Ice-pick tool. / Brain needles. / Words. Words. Words.

A long stretch of time to work on a project! I’ve never heard of such a thing. But I’m sure that running a publishing house (and by yourself) means spending days in the slush pile, working with authors on rewrites, editing all night long… when it comes to some of these challenges you describe--adapting your style, keeping up the suspense--has your work with Black Fountain Press offered any perspective?

It’s a difficult question, and I don’t really have an answer. I’ve always tried to keep things separate: my teacher’s job--where I also do a form of editing--my work for Black Fountain and my own writing. Black Fountain has only published two novels so far, and they are very different from mine, I feel. Then again, if you edit or proofread a manuscript, any manuscript, it forces you to look at details you would not necessarily spend time on as a normal reader. In that sense, I suppose editing is a useful exercise--like translation can be.

Thanks for your time, Anne-Marie.

My pleasure!