According to a report by the Idea Foundation, between 1990 and 2023, Luxembourg’s greenhouse gas emissions fell by around a third, while its population grew by 70%. This reduction is mainly linked to the transformation and , whose emissions have been divided by almost five. The residential sector and energy also contributed to the fall.

But these figures mask a more complex reality. Luxembourg remains one of the highest per capita emitters in the European Union, with 13 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year compared with an EU average of eight. This record is largely due to sales of cheap fuel to non-residents, which weigh heavily on the national balance sheet. If this “exported fuel” effect is removed, the total would fall to nine tonnes per capita, 11th in the European rankings instead of first.

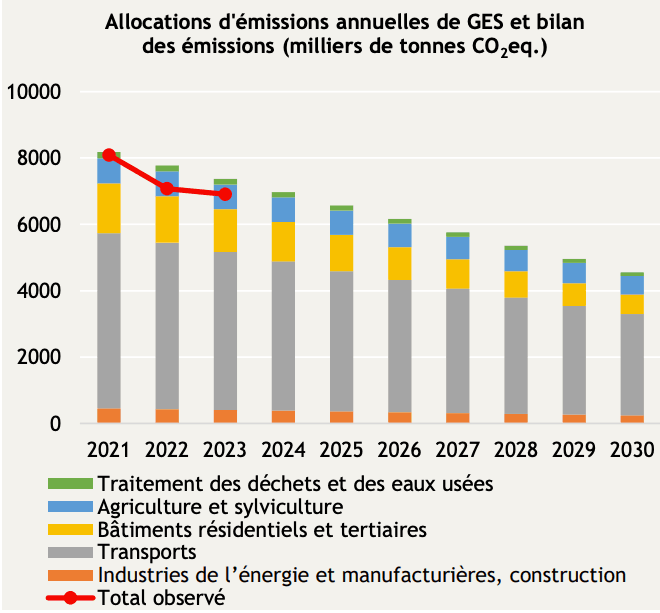

In its Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan (PNEC), Luxembourg has committed to reducing its emissions by 55% by 2030 (2005 baseline). To achieve this, the country is counting in particular on the , an increase in the carbon tax, and the . But the pace needs to pick up: the average annual reduction will need to almost double, from 3% to 5.8% between 2023 and 2030.

In 2023, emissions were 6.3% below the allocation set. Graph: Idea Foundation

The Greater Region: a balance close to Luxembourg

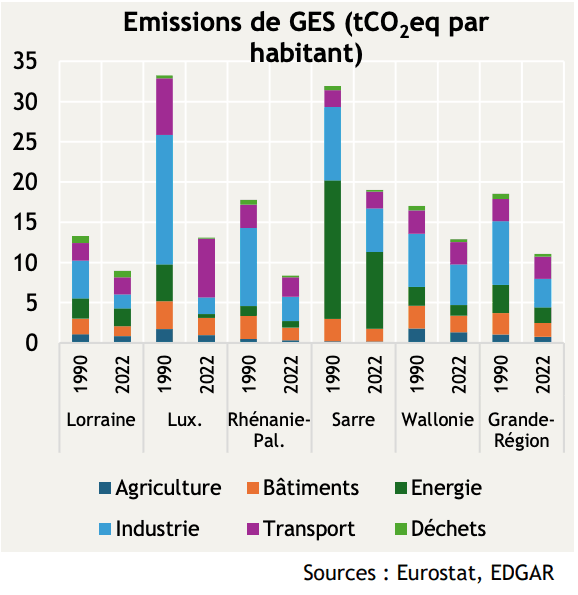

Luxembourg is no exception in its immediate neighbourhood. The Grand Region, made up of Lorraine, Wallonia, Saarland and Rhineland-Palatinate, has an average of 11.1 tonnes of CO2 per inhabitant, the fourth highest intensity in Europe if it formed a country. All its components exceed the EU average. And while Luxembourg is often singled out, it’s Saarland that holds the real local record, with 19 tonnes per capita, partly due to electricity production that is still very carbon intensive.

Vincent Hein, director of the Idea Fondation comments in the publication (“Les Trajectoires de Décarbonation dans la Grande Région”) that “the main driver of decarbonation in the Greater Region has been the industrial sector,” but “transport emissions, for their part, have fallen only marginally in 30 years.” The result: if current trends continue, the Grand Region will only achieve a 41% reduction in its emissions by 2030, well short of the European target of -55%.

The Grand Region’s emissions are higher than the EU average. Graph: Idea Fondation

In contrast to its members, the Greater Region as an entity does not have its own climate strategy. Yet the density of human and economic exchanges would justify shared governance of the transition. More than 200,000 border workers cross its borders every day, often by car, --the black spot for all the territories concerned, with virtually no reduction since 1990.

In his analysis, Hein argues for overcoming this institutional inertia: “The highly integrated nature of certain territories within the Greater Region, foremost among them Luxembourg, argues for concerted action that could positively accompany the climate transition.” In particular, the director mentions several potential levers:

—the coordination of local energy infrastructures

—the development of joint renewable energy projects or hydrogen

—greater synergy between similar industrial clusters (automotive, wood, eco-technologies)

—greater cooperation at university level to disseminate ecological innovations into the economic fabric

This article in French.