The EU directive on whistleblower protection was adopted in 2019 and member states had until 17 December 2021 to transpose the legislation into national law. The government last year from anti-corruption groups for failing to meet the deadline.

“It’s a text that concerns everyone and inter-ministerially we had to consult everyone and get them on board,” said justice minister Sam Tamson (Déi Gréng). While the directive covers only specific areas of EU law and breaches affecting the financial interests of the union and the internal market, Luxembourg has decided to extend its scope across all national law.

Under the act, whistleblowers are protected from being fired or otherwise punished by their employer. It requires companies of more than 50 employees to set up internal reporting procedures by December 2023. Larger companies of 250 or more employees must do so immediately.

However, a whistleblower is free to forgo internal reporting and turn straight to an external authority. They can also make the information public but in that case must be able to prove they had reasonable grounds to believe that the information they possess poses imminent or obvious danger to public interest or, for example, that the relevant authority is itself involved.

“It’s a matter of judgment,” said Tanson about what constitutes imminent or obvious danger, saying that the application of the text will help define this more clearly. As countries across the EU transpose and begin implementing the directive, “analyses will be coming on when imminent or obvious danger exists.”

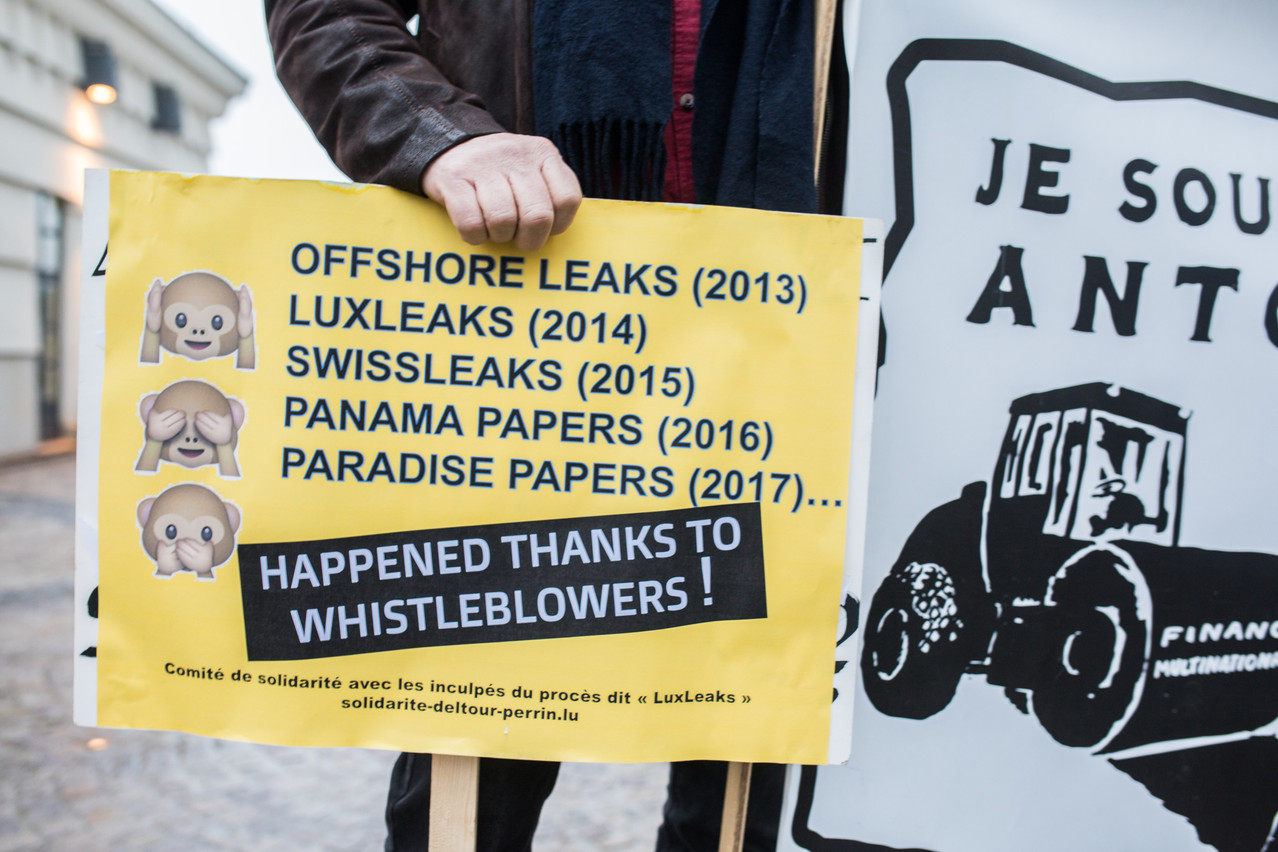

The justice minister would not comment on how the new laws would have benefitted Antoine Deltour, the whistleblower behind the LuxLeaks revelations who found himself in court for lifting the lid on hundreds of tax deals signed between the government and companies settled in the grand duchy.

Deltour was initially given a 12-month suspended sentence in 2016, which was finally overturned in 2018. The Court of Cassation affirmed Deltour’s whistleblower status, after this had been recognised by the European Court of Human Rights.

Information source

“There is a list of information that cannot be disclosed,” said Tanson. This includes cases linked to doctor-patient confidentiality, lawyer-client confidentiality or professional secrecy obligations for civil servants. However, protection can apply even in these cases if the whistleblower can show they acted in public interest.

The theft of information, for example through breaking into company premises or hacking a computer, can still be prosecuted, however. If information disclosed by a whistleblower turns out to be false, the whistleblower will be protected as long as they can prove they acted in good faith.

The directive extends protection to journalists or trade unions that help a whistleblower as well as offering a very broad definition of who is considered an employee of a company or organisation raising the alarm. Former staff, contract agents or even job applicants are also protected.

The draft law presented on 12 January must make its way through parliament, where it will be discussed in committee before coming to a vote in the plenary. It won’t replace existing obligations to report suspicious activities, for example in the financial sector or civil service.

While not required by the EU directive, Luxembourg plans to set up a whistleblower office under the authority of the justice ministry, which will help companies implement the new rules.

The office will also provide guidance and advice to people considering reporting wrongdoing internally, externally or publicly. The Netherlands in 2016 set up a similar project, the so-called House for Whistleblowers.

An annual report will show how many alerts authorities received by whistleblowers and how many investigations or procedures were launched as a result.