On 5 November 2014, a very turbulent period in the life of PwC Luxembourg began, which actually ended rather well if one recalls the shock that hit the auditing firm on that day. With the publication in several newspapers of what would become known as “LuxLeaks” came the revelation of the extent to which large multinationals in Luxembourg were benefitting from certain rulings. The practices were legal and used throughout Europe, but in Luxembourg they were being done on such an “industrial” scale that many people were shocked.

At the heart of the storm was PwC Luxembourg. And even if the firm was not the only one involved--all of the Big Four were implicated--it was on PwC that media attention would crystallise. This caught them off guard. One anecdote is enough to give an idea of the panic that reigned: a press conference was organised “on the spot” in the firm's new premises at the Cloche d'Or, where workers had just moved in only days earlier. The press conference was for local journalists from Luxembourg, Belgium and France, and television cameras were forbidden. Harsher still, guards forbade camera operators and press photographers from filming even the façade. No one remembers giving such an order and it caused quite a bit of chatter…

Communication errors, perhaps. We agree that some mistakes were made, including the restriction of this press conference to “local” journalists, as the international press grew ravenous for information, even going so far as to contact various officials at their homes.

First wave

Yet the firm was not caught cold. Almost two years earlier, an interview was aired on France 2’s brand new investigative programme, “Cash Investigation”. Wim Piot, PwC’s tax leader at the time, was confronted by Élise Lucet with the issue of tax deductions--the very same ones that would become the substance of LuxLeaks. He explained that the practice is common and legal, that nothing forbids this type of underlying structuring, and that essentially it is a deferral of taxation and not a pure and simple avoidance. But nobody heard him.

In the communications department, debriefings are quick: you quickly understand when you’ve been a bit naive. The firm also questioned the practice of rulings, checking with its lawyers and the government to make sure that the practices in question were legal. And it obviously investigated the source of the leaks, which had to be identified “quickly”.

The leak was made possible, for the record, by a Windows feature not previously documented by Microsoft: when data was transferred from one secure directory to another secure directory, the documents themselves were no longer secure.

And we thought that was the end of it.

An aftershock in the form of an earthquake

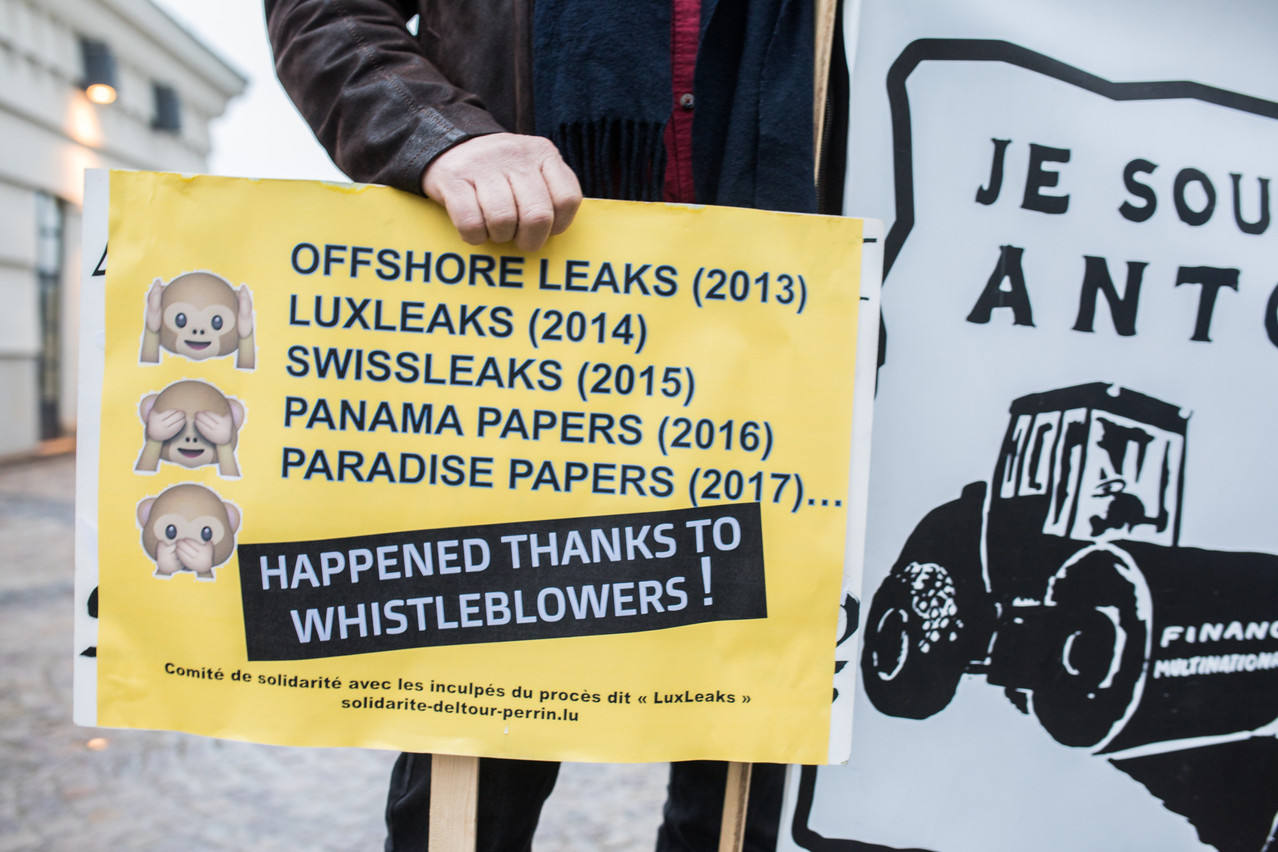

Eighteen months later, signs appeared that a second wave was on the way. In the spring of 2014, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) openly looked into LuxLeaks and contacted many of the Luxembourg actors. One of them was PwC, where it became clear that the documents from the first wave had been widely distributed and exploited.

The timing of this second wave has raised questions in many quarters because it coincided with Jean-Claude Juncker’s campaign to become president of the Commission. Coincidence or manipulation? Who can say? One reported fact is that the wave of publications initiated on 4 November had been planned for the previous June. It was only because the newspapers involved had difficulty coordinating that it happened five months later. Just days after the Juncker Commission took office.

The pressure on PwC from 5 November onwards was above all media pressure. Overwhelming media pressure. Faced with the aggressive dynamics of public scrutiny, arguments of good faith and regulatory compliance were inaudible and therefore useless. To the general public, at least. The firm also communicated with public authorities, customers and employees, where the message got through better.

Pressure from the network

The firm’s management also had to deal with another intense but little-known pressure: that of its network. PwC is a network of independent franchised firms that ultimately have only the brand in common. Every member has an obligation to protect it! The memory of Arthur Andersen's disappearance was still fresh and some members of the global board--the international body that coordinates the network and protects the brand--had reached an acute stage of paranoia, according to one observer. Of course, the network could not take control of the Luxembourg branch and replace its management--even if there were reports of temptations on that front-- but they could decide to exclude Luxembourg from the network. This was not a textbook case. The Luxembourg management had to fight to avoid that, and what saved them was ultimately that the network couldn’t afford to lose one of its flagships: “The network supported us because it had to.”

But many long nights were spent on the phone.

At the time of the outbreak, the question arose as to the grand opening of the new building. As a symbol of the resumption of events, the inauguration finally took place on 24 November 2014. It was like the end of a painful sequence, but one that launched or accelerated various projects in the areas of international taxation and whistleblower status. Projects that are still ongoing.

This article was originally published on Paperjam. It has been translated and edited for Delano.