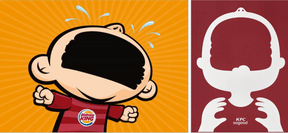

Paperjam: Do you remember the first ad you pinned? How Joe La Pompe was born?

Joe La Pompe: It was 25 years ago, in the agency where I was working. A Perrier campaign featured a holidaymaker on a beach, but wearing shorts made out a of down comforter to illustrate the extreme freshness of the drink. The idea was simple, the visual powerful. The creative director was very proud of it, even displaying it in his office and winning awards for it. He presented us with this ad as a model to follow. Until one day I stumbled across an almost identical ad for a British beer… from three years earlier. Same concept, same visual. I was stunned. I mentioned it to the creative, who replied, a little embarrassed, that it must have been a coincidence. But it was too similar. I published it for myself, as an archive. Then I looked for other cases, in magazines, books, on the internet… and I started to find them. Two, then three, then dozens. That’s when the project really took shape.

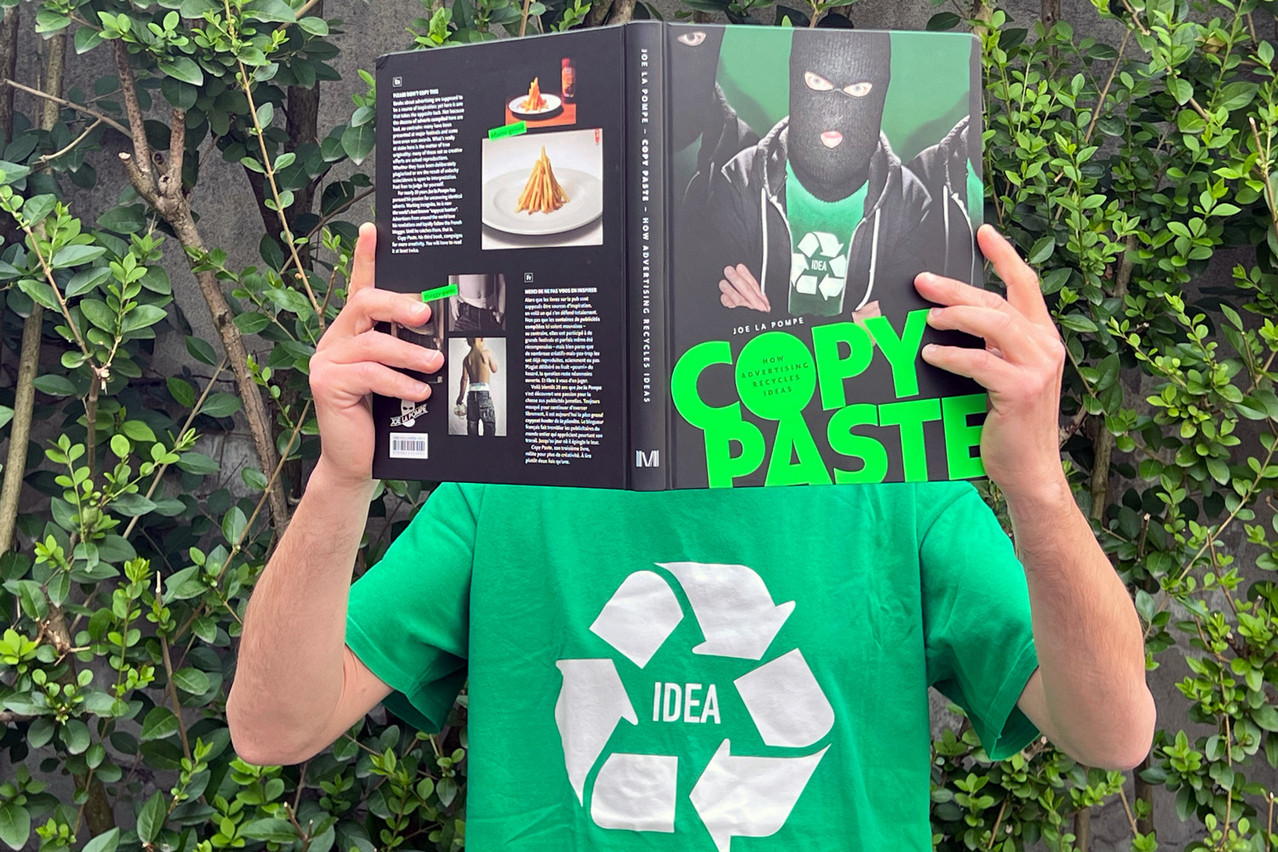

You always appear hooded. How do you manage this anonymity in your professional life? Do people close to you know your identity?

The balaclava is above all a character, a game. Initially, I didn’t wear a mask. But the subject of plagiarism is a sensitive one, sometimes frowned upon. As I was working in an agency at the time, anonymity protected me. The idea of the balaclava came later. Initially, I published from home, behind a computer. Then, as the site gained notoriety and the invitations, interviews and books came thick and fast, I had to find a way of not showing my face. I tried out several disguises, but none really suited me. I wanted something original, because I’m all about originality, and above all quick to put on. The balaclava was the obvious choice: it evokes a masked vigilante side that I find funny. I pair it with a T-shirt with a recycled logo, just to add a little lightness.

Your getup is reminiscent of Daft Punk or Banksy. Aren’t you a bit of a copycat yourself?

The analogy often comes up, but you have to put it into perspective. My character evolves in a very targeted B2B world. My work is not aimed at the general public. From the outset, I chose to focus on advertising plagiarism, a field I know inside out. It has already been suggested to me that I should expand into other disciplines, because plagiarism affects many other sectors--web design, logos or other creative disciplines--but I prefer to stay in a field that I know well. It’s a job that takes time, rigour and a real knowledge of the field. I leave it to others to explore other spheres.

This Perrier ad is the one that triggered Joe La Pompe’s mission. Photo: Joe la Pompe

Your mask intrigues, but so does your pseudonym. Why did you choose “Joe La Pompe”?

The name came about a bit by chance, without any strategy. In the agency, we used to call someone who copied “Joe La Pompe,” a colloquial expression that made me smile. “Joe” sounded good for a character and this provocative name, which evokes copying from the outset, quickly made an impression. It announced the controversy and contributed to the identity of the project. Internationally, it’s more vague: English speakers don’t always understand the meaning, some think my name is Joël, others that “La Pompe” is my surname. Today, it’s hard to go back, but if I had to do it all over again, I might choose another name.

You denounce ads from the four corners of the world, sometimes from unexpected countries like Brazil. How do you find these campaigns? It must be a time-consuming job, no?

Initially, I concentrated mainly on French advertising, as I’m originally from France. But I soon noticed that some local campaigns were taking ideas from elsewhere. Before the internet, art directors were inspired by foreign books or magazines and could pick up concepts without anyone noticing. Today, I keep an eye on campaigns from all over the world. Obviously, I can’t know everything, but I keep a close eye on the major advertising festivals, which offer an international panorama. I archive, compare and publish. My site, initially in French, quickly found a worldwide audience. I received messages from Indonesia, Africa, South America… Which prompted me to add a little English over time.

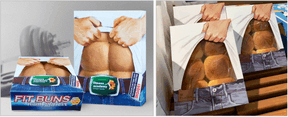

How do you spot a copied ad? Is it a hunter’s intuition or a well-honed method?

A bit of both. There’s intuition: I come across an advert and I have this reflex--“I’ve seen that before!”--so I put it aside and look for the source. Sometimes I find the original in a few minutes, sometimes years later, by chance. I receive a lot of messages, sometimes very well-argued, from people who act as whistleblowers. Then I sort them out. Some cases are very clear-cut, others much less so. I try to publish only the most glaring similarities. Sometimes two ads are sent to me just because they use the same typeface, the same word or a crocodile in the image… that’s not enough to talk about plagiarism. There’s also a real educational job to be done on what an original idea is.

Joe La Pompe, masked as usual. Photo: Emilio Naud/Paperjam

Where do you think the line between plagiarism and inspiration lies?

That’s the big question and it’s far from simple. I work alone, so there’s bound to be an element of subjectivity. My rule is that the two ads must be so similar that you instantly think, “that’s the same thing.” If a campaign reinterprets or enhances the original, I can choose not to publish it. It’s necessarily a personal decision. In fact, that’s the only time I interpret. The rest of the time, I simply put the images face to face. I never make a decision. I don’t say “this is plagiarism,” but rather “here are two campaigns that look alike: you judge.” My role is to document a phenomenon, not to pass verdicts.

Have you ever preferred a copy to the original?

Yes. Fortunately. It all depends on intention and execution. Many people simply copy without understanding, and the result is often mediocre. On the other hand, when an existing idea is used as a starting point, and you inject your own vision, added value, reinvention… then you change the register. It’s no longer really a copy. The most important thing is that the original idea serves as a springboard, not as the final destination.

In the age of AI and faced with the immensity of déjà vu, can we still be truly original or are we just rehashing what already exists?

First of all, has everything already been done? We often hear this idea, but I always add: not in every way. Most of the ads I see are still original. Formats change, media evolve, new forms of expression emerge. Advertising recycles, yes, but it transforms. And that’s not a problem: you can never create something out of nothing. Advertising is above all the art of absorbing trends and transforming them.

When it comes to AI, the issue is trickier. It can generate a striking image without telling you that it already exists. It’s a powerful tool for copying, but risky for creating. I saw, for example, an AI-generated image of a fish smoking a cigarette, supposedly to denounce marine pollution. It’s a powerful idea, but it’s one that’s been around for years in photomontage. The AI won’t warn you. This is a major limitation and a real risk for creators.

With digital tools, is plagiarism more frequent today or simply more visible?

Plagiarism has always existed. I thought that, with the internet, databases and image searches, it would be easier to prevent duplication. In reality, the volume of creative work has become such that it’s almost impossible to keep track of everything. Thousands of campaigns come out every year, on every medium, in every country. Even with today’s tools, finding an idea that has already been used is often like looking for a needle in a haystack. AI may be able to help here.

Do the cases of plagiarism you point to often result in legal action?

My site is more about creative ethics than law. Most of the cases published involve ideas taken from another country, another era or another sector. The real legal issues arise when two competing brands, in the same market, in the same country, end up with similar campaigns. This can lead to litigation, but it’s pretty rare. It is unlikely that a European brand will be attacked for using an idea that was distributed in Indonesia 20 years ago. It doesn’t end up in court, but it does end up on my site--which, for the creative people involved, can be just as damaging. It damages their credibility.

Have you ever--as an ad designer, I mean--crossed the line yourself?

Yes, twice. The first time, without realising it: a campaign that I thought was original already existed in Argentina. We took the ad out anyway, but I never sent it to festivals or added it to my portfolio. The second, more serious, was deliberate plagiarism. I was young, under pressure, in an agency where we had to present five creative ideas to the client in record time. I was 20 and short of ideas, and I remembered a cartoon I’d seen in a book. It wasn’t an advert, just an illustration. I took up the idea, thinking it would go unnoticed. The client loved it and this version was chosen. Too late to back out. I told myself that the author had died, that there would be no follow-up… but the day after publication, the cartoonist’s widow contacted the agency. A lawsuit followed, and the agency paid dearly. I almost lost my job. I tried to justify myself by saying “great minds think alike”… but I knew I'd crossed the line. It happened to me once and I promised myself I’d never get into a mess like that again.

This article in French.