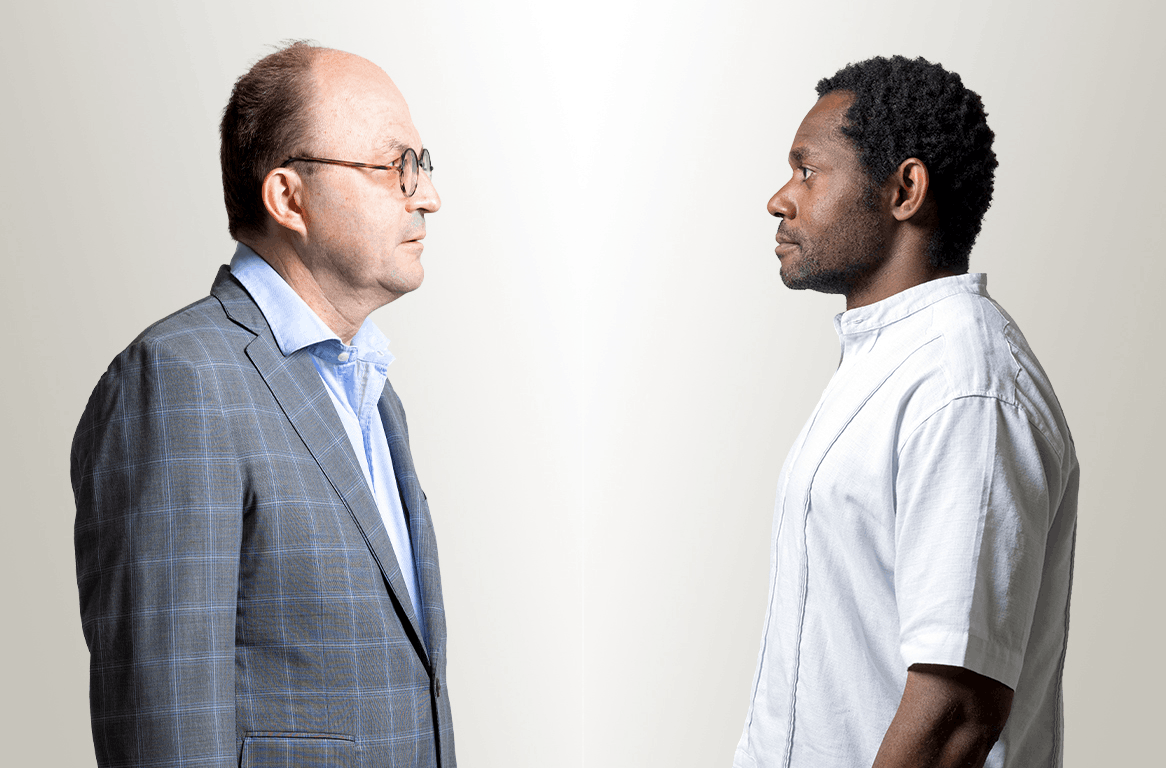

Ruben is an economist for the think tank. is the director general of the Chamber of Trades.

Tracy Heindrichs: The reduction of working time is a subject that comes up regularly in politics, like in 2016, 2019, and now. Do you think it comes from the political world or from the employees?

Tom Wirion: Well, there are no statistics or studies that I know of that have scientifically measured this, but I think I can say that a good half of the business leaders in the sector I work for would like to see a more flexible framework, with or without cutting working hours. But this working time reduction has to be considered on a case-by-case basis. I think that there is a certain demand from young and not so young people who say ‘I want to have more time with the family because I am a young mother or father’, or ‘I want to work because it is interesting but I want to have a few half-days where I can breathe’. This is a reality, and therefore the debate is a real debate and not a fictional debate. But I’m not sure that politics is leading the same debate.

Michel-Edouard Ruben: I have a feeling that it is more political. And I think it might be the politicians offering rather than the voters asking. For me, the demands of the employees are flexibility of working time rather than reduction. I think people are more interested in salary increases than in work decreases, but these are an economist’s assumptions.

Politicians are pushing out slogans. Overall, we have an organisation of working time that isn’t adapted to the metamorphosis of the wage society. Friction, discomfort, desires, demands and offers result from this. But when you look at it again, the question of the reduction and flexibilisation of working hours is the history of work. So it’s not surprising that demand exists, that offers are made. Having said that, today we are in a reality where we talk about a shortage of work. We need a framework that would be as flexible as all these possibilities--and this framework does not yet exist. So, to say in a simplified way that we’re going to reduce working time from eight to seven hours a day is missing something.

T.W.: It’s not what we need now.

To categorically say that everyone has to work 32 hours...

M.-E.R.: One size fits none here.

T.W.: If we say that we will make it more flexible with an accompanying reduction of working time, we have to offer a framework. But within that framework, or sector, we need companies and their employees to find common ground and the modalities to apply it. And for that to happen, we need to simplify and prune a lot of things which today make it very rigid and no longer in line with the metamorphosis. That’s why it’s a real subject. We [at the Chamber of Trades] are going to come up with concrete proposals in a few months.

There have been studies that have shown that a reduction in working time could improve productivity at the economic level. Can a reduction in working time help increase Luxembourg’s productivity or is that illusory?

M.-E.R.: The moment counts. We are living in a moment of tension on the labour supply. There is more of a demand for overtime rather than reducing working time. That being said, at the time of the pandemic crisis, we saw a forced reduction in working time. That’s why the notion of flexibility is important. But this idea that would consist today in saying that we must reduce working time to boost productivity is, for me, voodoo economics.

T.W.: I don’t think the time is right to consider it now. We’ll have to see how things develop. The fairly positive economic trend that existed in recent quarters is changing. So we need to look at the third quarter and the forecast for the fourth. There is a risk that the trend will decrease for the activity indicator. And in this case, we are in another film. We are then in a film where, yes, there is a reduction in working time, or perhaps redundancies.

Read also

So if we want to increase the country’s productivity, it’s not by reducing working time?

M.-E.R.: The reduction of working time is certainly a consequence of the increase in productivity, not the other way round. When you are in a context where there are productivity gains, well, they go into the economy. The best sector that shows this is the agricultural sector. The population continues to be fed today because there have been productivity gains. These have allowed wage gains, time gains, and the development of certain sectors such as leisure and services. Productivity gains are distributed, and not in the other direction.

If some sectors can afford to offer this, wouldn’t it penalise other sectors?

T.W.: The attractiveness of the employer is already an issue today. With the shortage, it is the employee who chooses their employer and who often has requirements. I think that once we have a new model and freedom in companies to find the right solutions in terms of working hours, etc., then there will be companies that will take advantage of the opportunity, others won’t. Then it’s the market that will regulate the rest. Today, due to the shortage, there are a lot of movements within the sector. So it’s already a reality today that employees who are less qualified will move for one euro more per hour, and the qualified for other criteria in addition to the salary, but that will always be the case. This is where the competition comes into play.

M.-E.R.: What in the short term may seem like a threat, in the long term is what makes the economy dynamic. What will happen is that there will be sectors that are ahead, and sectors that will be behind, and which, in order to continue to exist, will continue to use their own flexibility, their own capacity for innovation to catch up with the competition.

T.W.: And create productivity in the end.

M.-E.R.: Yes, in the short term it can create friction, but in the long term, it contributes to the dynamism and fluidity of the economy and ultimately to productivity.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.