“On the morning of October 26 […] we all felt a thrill of excitement at beholding a vast, lofty, and snow-clad mountain chain which opened out and covered the whole vista ahead. At last we had encountered an outpost of the great unknown continent and its cryptic world of frozen death.”

“It is an unfortunate fact that relatively obscure men like myself and my associates, connected only with a small university, have little chance of making an impression where matters of a wildly bizarre or highly controversial nature are concerned.”

These are not the words of Dr Olivier Francis, geophysicist at the University of Luxembourg and modern-day Antarctic researcher, but rather those of writer H.P. Lovecraft. The quotations come from At the Mountains of Madness, a landmark novella whose narrator ventures into Antarctica on a scientific expedition. Lovecraft treats the “great unknown continent” as a liminal space, a mental and geographical extremity. The weird and the uncanny are lurking there, waiting to interrupt your sense of reality.

I find this an appropriate, if admittedly grandiose, way to introduce Dr Francis and his experiences. Based in Belval, the professor has circled the globe for his work, from Yellowstone to Greenland to Saudi Arabia—but most memorably to Antarctica, where he has travelled several times for two- and three-week spells.

He has not discovered the horrifying ruins of an alien city, as Lovecraft’s narrator did, but his excursions nevertheless ring a chord with the fictional narrative. “You don’t come back from there without being touched and changed for life,” he told me.

![“All your relationships with people get screwed up [in Antarctica],” Dr Francis said. Photo: Olivier Francis](https://assets.paperjam.lu/images/articles/the-man-who-measures-gravity/0.5/0.5/640/426/417158.jpg)

“All your relationships with people get screwed up [in Antarctica],” Dr Francis said. Photo: Olivier Francis

“When you arrive, the first thing—of course—is the cold. But you knew about that. But then it’s the light. The light is incredible. You have to put on glasses immediately, you cannot see, it’s just… And then you discover you’ve lost your [sense of] smell. Because when it’s cold you don’t smell.”

But perhaps the most eerie description of the place is merely Dr Francis’s comment that, when you return, you’re changed. “You forget your PIN numbers. You don’t answer the phone when you come back. You start to be really disconnected from the world.” There are marriages, he added, that end after one person returns from the planet’s southern reach.

On the other side of that coin, however, “you make friendships for life.”

Dr Francis’s research is housed at the Princess Elisabeth Antarctica, an outpost known as “the Belgian station.” You get there by ice-hopping on a Douglass DC-3, a WWII-era propeller plane. I couldn’t help but notice that Lovecraft’s narrator, written into existence in the 1930s, flies in very similar two-prop Dornier aircraft.

The DC-3 takes off and lands directly on the ice. Photo: Olivier Francis

Listening to gravity

Just what Dr Francis does down there may be easier for him to grasp than the secrets in the polar wind, though it remains oblique for a layperson like me. A physicist specialised in geology, he basically takes very accurate measurements of gravity, with which he can help answer questions like: When will Antarctica start losing its ice? Is the Yellowstone supervolcano about to explode? How fast is Greenland melting?

On a more theoretical level, it’s all about gravity. Luxembourg, he told me—with a certain amount of scholarly glee—rises and falls 80 centimetres twice a day due to the attractive forces of the moon and sun. Such changes, or the “deformation” of the earth, affect all kinds of measurements. “If you have an airplane and you want to land on the earth,” Dr Francis pointed out, “you have to take into account that the crust is moving.”

The earth is elastic, he explained. And it isn’t just celestial bodies that affect the surface: the ice sheet in Greenland is so heavy that, over time, it pushes the crust downward. As a result, the environs surrounding the ice sheet rise in elevation. It’s like compressing putty into a bowl shape. After the ice melts, however, the ground will snap back into place. (“Snap” on a geological timescale.)

Stockholm, for instance, is currently snapping back into place: it’s rising 70 centimetres per century because the glacier that once towered three miles above it has now melted.

“So,” the professor concluded, “if you measure how fast Greenland is going up, you can determine how much ice is melting.”

The tricky part is that two separate things are affecting the crust underneath Greenland: present-day vertical displacement due to global warming; and long-term vertical displacement still happening from the last glaciation period (the one from 11,000 years ago). By combining GPS measurements (to measure elevation) and gravity observations, you can—well, Dr Francis can—differentiate the two signals in order to get the melting rate. His work in Antarctica follows a similar goal.

The Belgian station has the best food of any research station in Antarctica, said the Belgian researcher. Photo: Olivier Francis

In Yellowstone, the project is to determine whether the caldera—a supervolcano roughly the size of Luxembourg—is about to erupt. The concern is that, from 2002 to 2009, it was rising seven centimetres per year in places. If that’s due to the presence of magma, then an apocalyptic event is afoot, the possibility of which is certainly worth summoning a gravity specialist from the University of Luxembourg about. “We have no idea how Yellowstone is breathing and what’s happening,” the professor cheerfully told me, since they’ve only been doing measurements there for 20 years. “It’s very interesting.”

How can a gravimeter detect magma? “If the earth is going up, gravity should go down, because you’re going further away from the centre of mass of the earth,” he explained. So, first you measure the height change and the gravity; then you calculate the ratio between them. If the rising is due to thermal expansion, i.e. something that won’t blast Wyoming through the exosphere, you’ll get a predictable number. If that number is too low, however, it shows that gravity hasn’t decreased as much. And that’s bad. It means that something dense underground is pulling on the instrument, and that something would be… magma.

The project is still underway, since unfortunately the crust movements have slowed in Yellowstone to the point where no definitive readings can yet be taken. Still, Dr Francis reports that the supervolcano is not about to explode.

He is 80% sure of this.

But we’ll have to trust him because, perhaps surprisingly, few scientists worldwide are capable of taking these measurements. Nobody in the USA, Dr Francis thinks, is specialised enough for the Yellowstone job.

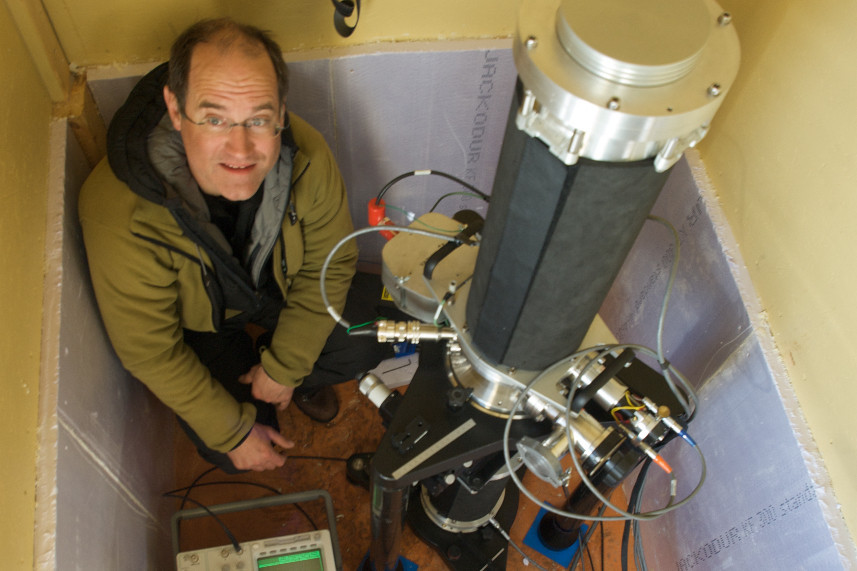

Dr Francis poses with one of his gravimeters, which is housed in a little hut in Antarctica. Photo: Olivier Francis

“My dream was Antarctica”

Through his many adventures, however, it’s the southward expeditions that really stand out. During his last trip to Lovecraft’s “cryptic world,” he told me, he performed a ritual: every night he took a little stool, walked 150 meters away from the research station, sat down, and thought about life.

“There are people there… they really find themselves.”

Dr Francis will speak more about his Antarctic experiences at the IAWIS/AIERTI conference, hosted (virtually) by the University of Luxembourg on 12–16 July.