Originally, this article was split into three parts. It is now published in full. The earlier version of the first part included some statements that were misleading and which the author deeply regrets.

It doesn’t take a business analyst to work out that language learning is valuable anywhere in the world. But here in Luxembourg, you don’t even need to be awake to realise it. Has anyone—ever—moved to the grand duchy and not taken a language class?

The private language learning sector is certainly alive and kicking, with a wide range of options for language-learners. Yet, compared to other professionals, it is often difficult for language teachers to secure CDI or even CDD contracts.

Freelance contracts

Delano reached out to several language companies to find out how many of their teachers are on freelance contracts. English World reported that 55% of their trainers are freelancers, but that these carry just a quarter of the course-load. At Inlingua, that number is 68% (15 freelancers versus seven employees). Berlitz director Philippe Salomon commented that “we normally work with freelancers only, but exceptions are possible”. Of the schools contacted, Prolingua appears to be the place most likely to grant contracts, with a 50% rate (36 freelancers versus 36 employees).

Harbani Singh has been a freelance English teacher in Luxembourg since 2014. She has taught at four language schools—Inlingua, Planet Langues, English World, and (now part of CCL Language Centres) Allingua—always on freelance contracts. In these roles she has made between €20 and €28 per teaching hour, but this, she explained, doesn’t represent the hourly working rate. In practice, teachers spend a little under half of their workweek on lesson-planning, marking, report-writing, administrative work, etc. For reference, at the state level a full-time workweek is measured at 22 teaching hours.

In answer to the question of whether she would have wanted a CDI at one of her previous employers, Harbani Singh (pictured) responded: “Absolutely, yes”. Photo: Harbani Singh

The mystery

Singh is a highly skilled worker: she has two master’s degrees and a CELTA, which is a well-known international language-teaching certificate. Still, the permanent contract has eluded her.

“I knew very few people who had full-time or CDI contracts,” Singh said, speaking about the private language schools where she worked. “And I was always jealous. I was like: ‘What? How?’ People said that, over the years, you’d probably be offered a [permanent] contract with the school. But nobody had the answers to how many years, and I knew a lot of older, very experienced teachers who didn’t have contracts.”

Switching to the present tense, she added: “I don’t know how you get the contract.”

As for the money, Singh explained that the language schools she was familiar with had the same hourly payment scheme. “I do remember having a discussion with one of the schools about the rate,” she said. “And they said that slowly it increases, depending on how long you’ve worked with us. But it didn’t seem to change very much over the years.”

“It can’t be your primary job,” she concluded. In her case, her household income is secured by her husband, who works at Amazon.

Another teacher, T.R. (whose request not to be identified we have respected), has taught at four different private language schools in Luxembourg over the past 25 years. About ten years ago one of these offered him a permanent contract.

The contract is part-time, with ten teaching hours a week remunerated at €1,200 per month. In practice, the school has always managed to provide more hours than that (currently he does 22 per week there), but what the contract offers is protection. For example, when the coronavirus pandemic hit and all teaching activity ceased for three months, he still made his €1,200.

T.R.’s contract also grants him five weeks of vacation, but they are unpaid.

He commented that, despite having a contract, he doesn’t feel like an employee. “I don’t feel like I’m part of a company,” he said. “I work alone.”

He noted that his company’s main use, to him, is finding clients. “They don’t do anything, to be honest,” he said. “I prepare the courses; I write the reports; I test people [i.e. carry out level assessments]. So what do they do? They give names.” Major clients wouldn’t normally hire private language teachers, he pointed out, so, granted, names are valuable.

Ultimately, and despite his rare luck in having a contract, T.R. is frustrated about the industry. “We’re underpaid,” he said plainly. “Especially when you realise that they charge €60 per hour and only pay you half of that.”

He reported that he is, in fact, feeling forced to leave the profession altogether, even though he loves to teach.

Difficult environment

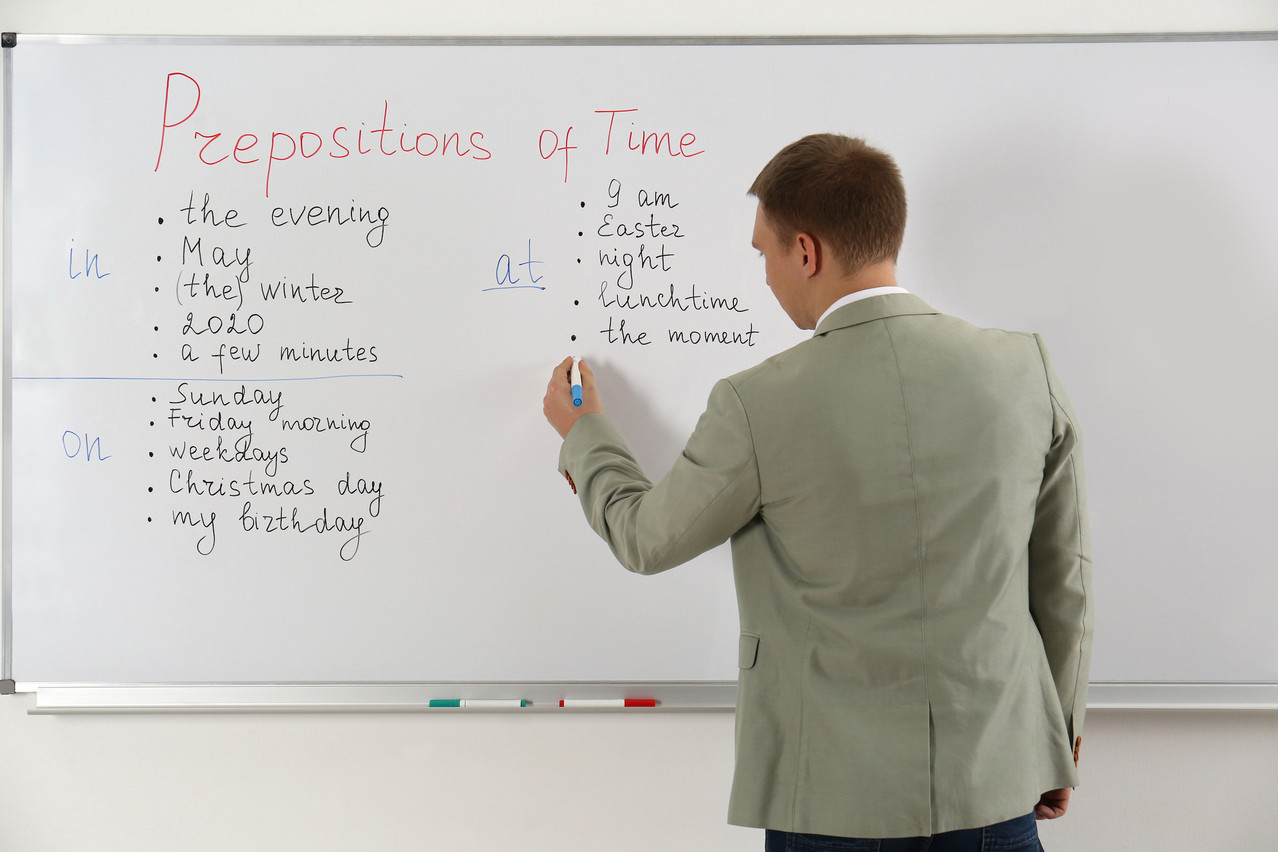

As employers, language schools have a unique problem: irregular, shortened business hours. Corporate and individual clients rarely have flexible timetables, which means that the demand for lunchtime and evening courses is disproportionately high. As a result, there may be enough hours to fill a workweek, but because they aren’t spread out no single teacher can do them all. Schools thus need more teachers, each with fewer daily hours, to meet these demands.

This was a problem cited by Jean-Pierre Piersanti, who founded Inlingua Luxembourg in 1993 and was its CEO until 2020, as well as by Clara Moraru, who runs Languages.lu and is also campaigning for better freelancer conditions.

“We have to respect the clients’ wishes,” said Piersanti, adding that teachers might give Saturday and Sunday classes to kids in addition to lunchtime and evening sessions where they travel to a corporate client’s premises. “This is an eclectic schedule [for the teacher]. It’s very difficult for them.”

“You cannot make it work unless the teacher works crazy hours,” said Moraru. “Early mornings, lunchtimes, evenings. And of course they don’t want to work from 7:00am until 8:30pm… that’s not a life.” Employing teachers means imposing schedules on them, she summed up, from erratic weekly timetables to keeping them in town during holiday months.

Both CEOs claimed that, as a result of these difficulties, not all teachers wanted contracts. Even part-time contracts, said Moraru, were a difficult sell because of the hard schedule. Piersanti reasoned that some teachers prefer the freelancing arrangement so that they can organise their own timetables or because they want to be entrepreneurs.

Piersanti did give examples where CDI or CDD contracts were possible. Most recently, in 2021 Inlingua won a contract with unemployment agency ADEM to give French language and assimilation courses to immigrants. Because they were jobless, the immigrants could attend classes all day every day. “It was excellent,” said Piersanti. “We employed three teachers, full time.” These were CDD contracts that lasted 20 months.

He also described efforts to find enough hours for a contract by bolstering the position with non-teaching duties: if, besides giving courses, a teacher engages in pedagogical development, reception work, and other administrative duties, then it is sometimes possible to offer a contract. He added that Inlingua is aiming to improve its freelance/contracted ratio to half-and-half within the next three years.

Competition from everywhere

There might be more to the story, however. Moraru suggested that there is an invisible factor that helps explain why these difficulties persist. It’s societal in nature: the belief that teaching a language is easy to do, compounded with the total lack of any barriers to entry to the profession.

It is indeed well-known that language teaching has often been used as a passport, stopgap or hobby. Piersanti described the high numbers of British teachers who (before Brexit) came to Luxembourg and worked at Inlingua for a year while they searched for jobs within their specific field—which wasn’t languages. Other teachers might be retirees who want to share their knowledge or college grads who simply want to make some extra money while they live abroad and discover a new culture.

Because of the prevalence of such teachers (”You can’t imagine the number,” said Piersanti of the incoming British English teachers), the supply remains high. On top of that, the former Inlingua CEO also pointed out that many non-school bodies offer language courses nowadays, including the City of Luxembourg, the Association for the Support of Immigrant Workers (ASTI), the Red Cross, etc. Moraru added that many people who have passed the Luxembourgish Sproochentest—necessary for the citizenship application—turn around and give classes on how to pass the exam, even though their Luxembourgish may still be elementary.

Some of these teachers are serious about the profession, but not all. Moraru made the observation that it’s difficult to tell the difference. “How can you evaluate a good teacher or a bad one? You actually have to go to the training and see how much you learn. But this takes time.”

“To become a teacher,” she went on, “we go through specific studies. We go to university, we do master’s degrees, etc. However, there are also people with no studies, or young people like teenagers, who give ‘extra support’… and the difference between what these kids make and a very competent and experienced teacher—it’s very low.”

The author would like apologise to anybody who read the earlier version of the first part of this article and received a misleading picture of his intent as well as of certain facts.