In my hometown of Columbus, Ohio, businesses made preparations on Monday by boarding up their facades in case of unrest on and after Election Day.

Some of the buildings are just steps from the Ohio statehouse, where demonstrations recently took place as part of the Black Lives Matter movement and anti-masker protests. In July, a 1955 sculpture by Edoardo Alfieri titled Christopher Columbus, after whom my hometown was named, was removed from city hall after protesters demanded it come down because of Columbus’ history of exploitation of Native people.

Ohio is among many states to have also readied the National Guard to help keep peace if elections get out of hand. And in what NPR calls “a sign of the times”, others cities are bracing for unrest, including the nation’s capital in Washington, DC.

The New York Times put it well: “Plywood is never a comforting sign. It suggests chaos and riots, hunkering down and hurricanes. Elections? That’s not how it is supposed to go here…there is something about seeing plywood in the nation’s capital that can seem especially chilling.”

This election is indeed unprecedented, with millions of voters having cast their ballots early or absentee. But more so for many Americans, it feels deeply personal. My own Columbus friends and colleagues have made comparisons of the city to a warzone. Congressman Steve Stivers, representing Ohio’s 15th Congressional District, said in a social media post that downtown reminded him of Beirut. “I urge everyone to remain calm even if your candidates lose,” he wrote. “Nothing defines our constitutional republic more than a peaceful transition of power.”

In a country that I remember for its grassroots movements and communities lifting each other up, indeed all of this feels foreign.

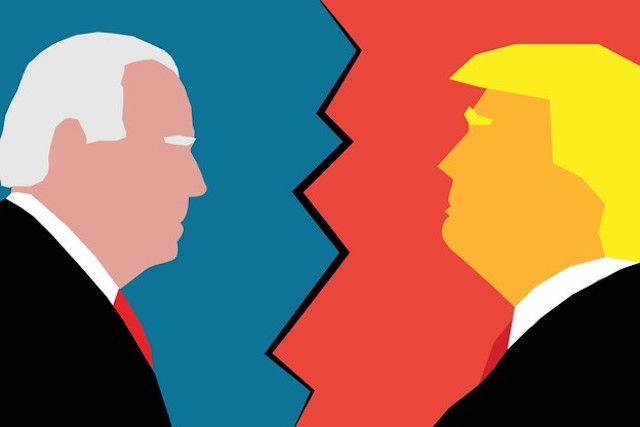

As the US is entering its biggest democratic exercise this 3 November, it simultaneously feels as though there is the largest dichotomy: on one hand, over 98m people have voted early or absentee--which should feel like a cohesive glue to pull the nation together--but on the other hand, there is a potential for civil unrest.

Needless to say, I’ve been watching Ohio closely--the “Buckeye state” has sided with the presidential winner in the last 14 elections--and where its 18 electoral votes will go is anybody’s guess. With several of my own relatives having built their careers in state politics, mainly as Republicans (but in my early memories, those Republicans were quite different than the party we see today), I’ve felt that same dichotomy on a personal level, too. The debates I’ve had with friends and family have been heated well over four years now, but what has most surprised me is that the debates seem to have finally paid off: at least a couple of them have told me quietly that this year, even if they voted for Trump in the last election, they refuse to vote him in again. But they refuse to vote for Biden, instead opting to write-in other candidates.

Republican leaders of this country MUST stand up and defend the integrity of this election. Their silence these recent months about Trump's rhetoric is threatening the future of our democracy. They need to find their courage and speak out. #Election2020 pic.twitter.com/mFuXAbUKLt

— John Kasich (@JohnKasich) November 3, 2020

What finally pushed them? I’ve wondered. In some cases, they refer to a lack of professionalism and lies of the Trump administration. The reaction to the covid-19 pandemic could have been better handled, they point out. But Republicans speaking out against Trump--such as former Ohio governor and candidate for the 2016 Republican Party presidential nomination, John Kasich--also seem to have a greater hold over these middle-grounders than I had considered. Kasich has been vocal about the need for his party to get back on track and has said “it’s a dangerous situation when a big chunk of Americans think the election result is not legitimate. [Trump]’s rhetoric is largely to blame. It’s critical that the leaders of both parties speak with one voice (regardless who wins) confirming the legitimacy of the results.”

What has surprised me, however, in the run-up to these elections is that some of the Democrats and Republicans with whom I’ve spoken, share common concerns: the threat of big businesses, the tearing apart of the basic fundamentals upon which the US was founded, the growing deficit and wealth gaps, to name a few. And members of both parties are concerned that the opposing party will be to blame for riots following the elections.

The two main parties should attempt to align on these common grounds, and in my opinion both Republicans and Democrats need to critically reassess their parties. But it will take time to rebuild trust and listen to each other, to heal the democratic foundations, no matter who the winner. My only hope is that the democratic process and transition be a peaceful one.