Boyd van Hoeij: The film “Dreams Have a Language” started as an extension of Sylvie Blocher’s synonymous installation. How did you become involved?

Donato Rotunno: I met Sylvie for the first time some 10 years ago, by chance. I was working on a film with Izima Kaoru, “Landscape with a Corpse”, which was also a cross-media project, composed of his photographic work, a making-off shot in Japan, and a fictional component. And for that project I was at the Casino, where Sylvie had an exhibition.

Many years later, Enrico Lunghi asked me whether I would be interested in exploring a collaboration with her in the context of an exhibition they were preparing. The idea was that it would be an encounter of both our worlds and very quickly, I realized that we had to find out how we could enrich the work of each other in this project, which would have to become something new and different, something that went beyond just the exhibition.

What were your first ideas?

We came up with this idea of a series of Russian dolls, in which the work of one person stays intact but it’s possible to add another layer on top of it that turns it into something else. This approach was similar to what I’d done with Kaoru. The advantage is that there’s a process of discovery of one thing inside another and that there’s no direct competition between the different elements; they simply exist alongside one another.

So the idea was to take her exhibition and turn it into a first building block of the film. Her voice-over was also part of the project from the start for me. It is important to hear Sylvie because the exhibition is hers; it’s about her view of the world. I, as a director, can offer my view on her work but with some distance. What interested me was the transformation of the act of bearing witness, which the people did in the greenhouse, into something fictional. So after the exhibition, we transformed the interview material into something more fictional.

French artist Sylvie Blocher speaks to one of her interviewees. Photo: Tarantula

How did the project evolve?

Our relationship evolved as our screenplay evolved. Sylvie is a solitary contemporary artist, someone who works alone, in her head. While cinema, what I do, is a collective art. She can work with a pencil and a piece of paper but I need a crew and equipment, cameramen, an editor, a sound mixer. But I think that the final result is both a reflection of my work and myself and a reflection of her and her work.

Let’s talk about that fictionalization of reality, which is a key theme of the film and also seems to have been a major part of your process.

We transcribed the greenhouse interviews and this helped us look for both the right interviewees and the right words. Sometimes, we cheated and put the words of one interviewee into the mouth of another, so that’s already a manipulation that fictionalizes reality. Then we exchanged ideas as we wrote the screenplay, which I have more experience with than Sylvie but which was always done in collaboration with her.

And then we shot the fictional part. So some real people walked into a museum, talked about their ideas, then became actors of their own or even someone else’s story. That transformation fascinates me, as these non-professional actors were feeling and thinking about things that weren’t necessarily theirs.

For me, it is also a film about the necessity of fiction, about how fiction can be used to understand reality better…

I think fiction is a dream; fiction is what is possible when you bring your imagination to something. The world we suggest in part one is sad, grey, painful and difficult to live in. It is the everyday, which, in our film, is unbearable and only the imagination can take us out of it and make us soar. It takes something intangible. So we imagined this world in which humanity could start over and the MUDAM was the last bastion of humanity that had to be reopened but to a new world, a changed world.

I like this very oppressive, Lynchian passage where the dictator tries to reassure everyone that everything’s fine, that they should all stay with him and that someone then decides: “I need to leave, I want to breathe”. So there’s the opposition of the interior versus the exterior; what’s forbidden versus what we have to obey and the transgression that allows someone to leave that bubble and go towards something that’s like a dream. This kind of action can only be suggested through poetry, I think, not words.

That’s why the character says: “There is nothing left to say”. In the last 12 minutes, there is an attempt, composed of dance, poetry and dreams, to create a floating state, to float between the earth that attracts us and the possibility of the sky to, somehow, make us soar as if in a dream.

A woman from Rwanda cries during the interview with Sylvie Photo: Tarantula

However, this need for a fictional gateway out of the misery of reality is in some ways analogous to the way the interviewees detached themselves from the ground in part one...

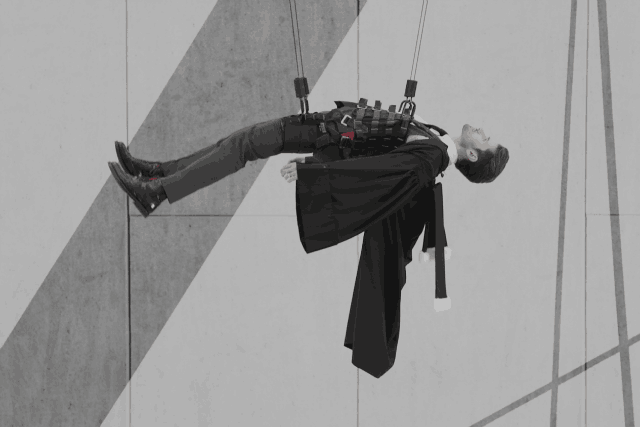

At the start, there is a mechanical device that forces people to become detached from the ground. But we can already feel it has some kind of impact, that there’s an emotion that’s provoked by this mechanical effect. And talking about yourself when you’re floating in the air, ten meters off the ground, is not the same as talking about yourself with your feet on the ground. This transformation is real, though it doesn’t work for everyone. Our idea was to think about how we could capture this kind of phenomenon without having to rely on a mechanical effect. And the answer is: through writing, through fiction.

How would you describe the differences between parts one and two and how did they affect your directorial choices?

As soon as we talk about fiction, we talk about actors and performances. And a mise-en-scene of all the elements becomes necessary. We don’t film the beginning in the same way as we film the end; the cinematic language evolves. There are several types of images in part one. Firstly, there’s the record of what happened during the exhibition. Then, there’s a more intrusive camera that steals little moments here and there; a look, or a hesitation.

Thirdly, we had the images that were part of the exhibition at a lower level. These three types of images work together. Then there’s a transition, with a fade to the night and the exterior. As the rhythm and the colour grading changes, the image becomes almost bichrome, though as a viewer you get used to this remarkably quickly. And we have the floating drone footage, which detaches the viewer from the earth.

At the end of the film, there’s a sense that we’re going back to the beginning, to the real world. After a transformation, we’re back to where we started…

Yes and this is indispensable for Sylvie as an artist as well, because the inspiration for her work comes from the real world. I like the ending because we can’t go beyond that, everything stops and there is nowhere else to go. That’s a permanent contradiction we carry inside all of us; we all dream but then we wake up again and we are condemned to this constant reawakening.

Not everyone manages to dream and you can even see this in politics today. It’s not so much about dreams and ideals anymore but how to solve everyday problems. People don’t dream about leaving the building, so to speak, to take a look outside. How can we offer dreams to the world we live in? Some people find them in drugs. And we can do it in literature, theatre, music--and cinema.