Digital memory banks have been around in the US since they were first used to rapidly gather documents relating to the 11 September attacks. Thanks to technological advances, today museums are running with the concept, no longer waiting for archived material to come to them decades or even centuries after an event or crisis but actively appealing for current objects.

“Historians brought this idea to digital history and the idea of virtual memory emerged where people can contribute their own experiences, ideas, memories, objects, photos, videos etc, to a memory bank platform,” said Stefan Krebs, a historian who is part of a team at the University of Luxembourg’s centre for contemporary digital history (C2DH) that created Covid-19 memories.

The platform went live on 10 April, and within a month had 180 submissions, including texts, photos and videos.

It is an impressive effort considering that the team only began working on the project on 23 March and have had to coordinate everything from their respective home offices.

A team of a dozen curators screens submissions to ensure they do not infringe rules on advertising, spam or cause offence. “We all do this as a side job,” Krebs said, adding that verifying submissions can be tricky. “There’s a grayzone. What do you do if people document how the shopping experience is today in a particular supermarket in Luxembourg? If the logo is shown, is it an advert? Or is this a document of the crisis?.”

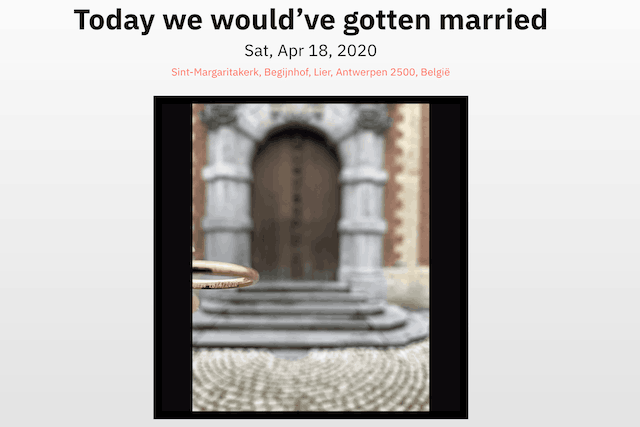

Screengrab shows a light-hearted post from the Covid-19 memories platform.

The evolution of the kinds of submissions has been interesting, says Krebs. At the start of lockdown, many of the submissions featured photos and video of silent, empty streets. “But lately we got some submissions where people tell us how difficult it is,” Krebs says. Among them, are posts describing the trials of home schooling, isolation and a particularly poignant post about losing a grandmother and being unable to return home to comfort family because of restrictions on movement and social distancing. Krebs says the goal is to encourage people, both residents and cross-border workers, to share all experiences, good and bad.

“In general, we’re interested in how the confinement impacted daily life. How was family life with social distancing, how was it not to see parents or grandparents, how was it to arrange teleworking, especially when you had children at home?”

Alongside the public platform, historians at the university are gathering testimonials from health sector workers in Luxembourg. They have some 90 interviews and 30 hours of video, some of which will be uploaded to the site. And the idea is to extend this oral history element to include people working in other frontline workers, for instance supermarket cashiers.

“It’s clear from the sheer impact of the coronavirus, that we will look back in 20, 50, 100 years and ask what happened?” Krebs says, adding that while government archive sources will be plentiful, the experience of the average person is less easy to gather after the fact. And it is not only the historical perspective of covid-19 memories that is important.

“We also hope that we can help people to better cope with the whole situation, by showing people they are not alone in these times of isolation and confinement: that other people have the same ideas and perceptions,” says Krebs.