According to a French proverb “travel shapes youth” and Grand Duchy students can vouch for that.

The Unesco Institute for Statistics says Luxembourg is one of the rare countries in the world that has more students studying abroad than at home. While the top three destinations are Germany, Belgium and France, the UK is the fourth most popular choice.

Last year, 1,219 young residents asked for financial aid to study in the UK. But since the Brexit vote these students--and all those who had plans to follow their path across the Channel--have expressed understandable concerns. Not only because they are apprehensive about the less welcoming environment, but also because costs might go up and admissions become more difficult.

Currently, Luxembourg (and other EU) undergraduate students pay the same university fees as UK students, the so-called “home fee” (maximum £9,000 per year). Non-EU students pay a higher “overseas fee” (from around £4,000 more per year up to three times the home fee). Nobody knows what agreements will be made once the UK exits the EU, but additional hurdles are expected.

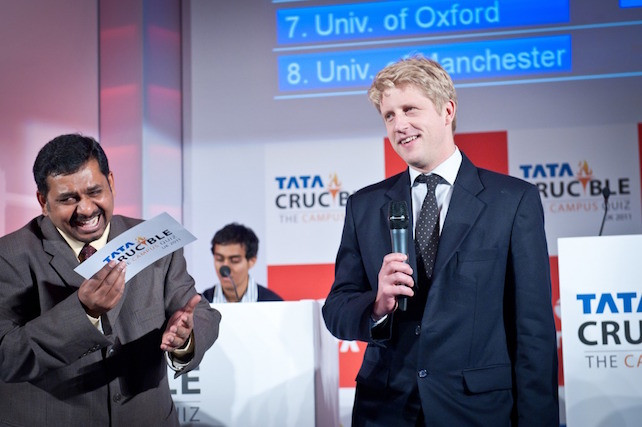

However, those already studying in a UK university, and those starting in 2017, have been promised they will be able to do so under present regulations. “International students make an important contribution to our world-class universities, and we want that to continue,” Jo Johnson, Britain’s universities minister, stated shortly after the EU referendum result. These students “will have their eligibility maintained throughout the duration of their course [which] will provide important stability for both universities and students.”

Universities UK welcomed the announcement, but is now calling on the British government to provide similar reassurances to EU students who want to apply for courses starting in the 2018-19 academic year. “Throughout the transition period our focus will be on securing support that allows our universities to continue to be global in their outlook,” says Julia Goodfellow, president of Universities UK (UUK).

In July 2015, the then home secretary, Theresa May, wrote to other ministers in a (later leaked) letter saying universities should “develop sustainable funding models that are not so dependent on international students.” But universities were already aware that political rhetoric was starting to discourage students from abroad.

Two years prior, Sheffield University and its student union launched a #WeAreInternational lobbying campaign. More than 100 universities and organisations across the UK have since joined forces to advocate for international students, staff, research and collaborations for higher education and, since the Brexit vote, their mission seems all the more important.

While it’s clear that Luxembourg and other EU students can count UK universities and numerous organisations as their allies, there is no way of knowing if that will be enough after 2018.

This article was first published in the Winter 2017 issue of Delano magazine. Be the first to read Delano articles on paper before they’re posted online, plus read exclusive features and interviews that only appear in the print edition, by subscribing online.