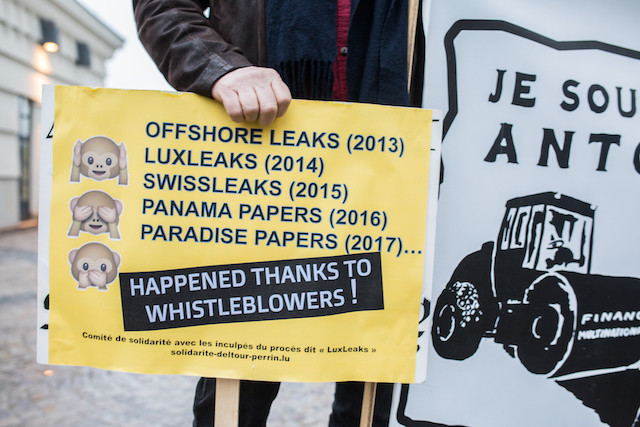

On 5 November 2014, the first of what became known as the LuxLeaks files were published, lifting the lid on hundreds of tax deals signed between the government and companies settled in the grand duchy.

Antoine Deltour--the main leak source--was awarded the European Citizens’ Prize for his actions but still found himself in court. His 2016 12-month suspended sentence was finally overturned in 2018. The Court of Cassation affirmed Deltour’s whistleblower status, after this had been recognised by the European Court of Human Rights.

The EU directive since adopted could have protected him and other whistleblowers, said Dimitrios Kafteranis, a researcher at the University of Luxembourg who is writing his PhD on the directive. The document is a big step forward, he said. “Five years ago, it would have been unthinkable.” And even though transparency activists have said the directive sets minimum standards only, “the most important thing is that we have a directive at EU-level at all,” Kafteranis said.

Its strengths lie in a broad definition of “worker”, meaning that former employees, contract agents or even job applicants are also protected by the directive. There is also no requirement to report wrongdoing internally before raising the matter with authorities.

This was a solution also favoured by Luxembourg, a spokeswoman for the justice ministry told Delano. France--which already had a reporting hierarchy in place--opposed being able to skip internal reporting, according to Kafteranis.

Additionally, the burden of proof is with the employer rather than the whistleblower.

“The directive also abolishes the good faith requirement,” said Kafteranis. The emphasis now is on the information being passed on, which the whistleblower needs to have reasonable grounds to believe is true. “The directive doesn’t allow abusive reporting and refers to the need to protect the public interest,” Kafteranis said.

Broaden the scope

Antoine Deltour at a 2018 court session. Photo: Edouard Olszewski

But the transposition of the directive will be another matter, as countries can broaden the scope if they want to.

For example, the directive only covers ten areas of EU law--such as financial services, public health and data protection--as well as breaches affecting the financial interests of the union and the internal market, including arrangements to gain a tax advantage.

Justice minister Sam Tanson has already said Luxembourg would aim for what is called a horizontal transposition of the directive, meaning it would apply to all national law, too. The ministry is preparing to present its draft law to transpose the directive at the start of next year, the spokeswoman said. Member countries need to have legislation in place by 17 December 2021 or risk sanctions from the European Commission.

The Netherlands as part of its new laws has set up a House for Whistleblowers, providing guidance and advice to people considering reporting wrongdoing either internally or externally--an option also being explored by Luxembourg, the ministry spokeswoman said.

“Whistleblowers aren’t always lawyers,” said Kafteranis. “It can be complicated to understand what protections they fall under.” In addition to the right to whistleblowing there are also reporting duties in several sectors, for example in the case of money laundering. “You can be punished for not reporting this,” said Kafteranis, adding that there is often confusion between rights and obligations in different scenarios. “The directive confuses some of this, too.”

Further to offering protection, “adopting the directive will hopefully change the culture,” said Kafteranis. Whistleblowing in many parts of Europe is still regarded negatively. “It reminds us of some of the darkest moments in European history,” he said. It is associated with snitching or ratting someone out. People in Europe are also traditionally more attached to their employer, he said. “It’s like family,” making reporting wrongdoing difficult.

Countries like the US, where whistleblowers can even expect financial rewards, have a much different attitude. “The US had its first whistleblowing law in the 18th century,” Kafteranis said. “There’s a gap of 300 years.”